You’d be hard pressed to find a more inviting and well-considered breakfast cookbook than Breakfast: Recipes to Wake Up For (Rizzoli, New York, NY, 2015), by George Weld and Evan Hanczor, the founder and chef, respectively, of Williamsburg, Brooklyn’s renowned farm-to-table restaurant, Egg. With a focus on classic southern staples (think grits, greens, bacon, eggs, and country ham) and quite a few unusual ideas for breakfast (parsnip and apple soup, broiled tomatoes, and smoked trout salad, anyone?), the book is a homage to the power of good ingredients simply prepared and the fun of learning to cook new things.

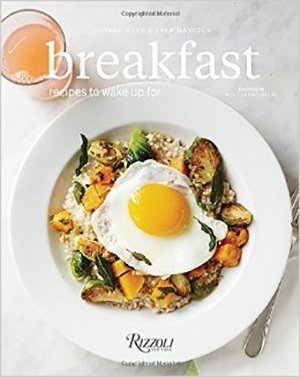

Gorgeous photos by Bryan Gardner accompany recipes for making everything from humble scrambled eggs to more advanced fare like duck confit and fried oysters. There are recipes for dressings, desserts, sides, and plenty of egg dishes. And if you’re up for a real challenge, there are even directions for making your own cured bacon, sausage, and scrapple.

But no matter how seemingly complex the dish, the book’s clear directions take you by the hand to clear up common confusions, noting when the authors’ preferred methods differ from standard approaches and what experience–whether it was restaurant experimentation or the expediency needed for home preparations–led to the recommended divergence. The book is also intimately personal, with reminiscences of Weld’s southern childhood, family meals, and tales from the restaurant. With his evocative and casual writing style, Weld paints pictures that makes you want to head to the nearest log cabin, whip out the cast-iron skillet, and start cooking!

If you’ve ever been to Egg, you’ll recognize many of the book’s dishes from its menu. Having enjoyed and reviewed a delicious meal there, I can attest that they’ve mastered the art of simple preparations of quality foods like heirloom meats, local organic flours, local eggs and dairy, and fruit and veggies from Goatfell Farm, their own upstate NY farm. While fairly straightforward, the dishes I had were all winners: unassuming yet perfectly satisfying bacon, fluffy scrambled eggs, pancakes dripping with Vermont maple syrup and peppery biscuits and gravy. With fare so basic, some of the recipes in the book come off as humorously simple at first glance, but as with the restaurant, the book’s methods are carefully crafted to step out of the way and let the quality of ingredients shine in ways you didn’t know possible.

As I read through the recipes, it dawned on me that many of the most important roles in the book are supporting ones. Weld’s description of his preferred ingredients and spices, like molasses, black pepper, apple cider vinegar, turbinado sugar (unlike refined white sugar, turbinado retains some of the molasses flavor from the cane), and when and how to use these simple but powerful partnering flavors, turned out to be the key to understanding the magical directness of his dishes.

So, to road test a handful of the book’s more tempting recipes and methods (and to see if they could work with a cook as inexperienced as me), I made a trip to the store. First up: eggs. Weld tells us that cooking eggs is one of his restaurant’s first tests for new chefs–a way to determine if they’re humble enough to relearn or unlearn bad techniques. As someone who never much cared for eggs (beyond the standard scrambled variety), I took the cookbook as a challenge to try and broaden my horizons in that department by attempting its recipe for poached eggs–the dish that Weld claims brought him back to the egg fold after years of being served poorly executed eggs–and see if they could entice me back too.

Having never made them myself, I was impressed by how easy it is if you take the time to follow the book’s few simple directions. I made mine as part of an eggs benedict with spinach, basil, bacon, and homemade hollandaise. Even though I lacked the helpful slotted spoon for transferring the egg from the boiling water, it ended up as one of the best breakfast dishes I’ve ever whipped up. (A second attempt fared even better with a friend’s tip to stir the water and create a vortex to hold the egg together.)

The recipe for scrambled eggs was also illuminating in that it advised adding the butter to the pan with the eggs–not before–so that the water in the butter would inflate the egg with its steam to make it fluffier. And it totally was. Not content to end the egg journey there, I also attempted the book’s beet-pickled hard-boiled eggs, which turned out not only as beautiful as the book’s photos (thanks to the bright red beets) but much more delicately flavored with tangy, cidery garlic than I had imagined. Quite the treat. And as Weld notes, when “sliced open, so that the dark yellow yolk is exposed (against the vivid fuchsia), they’re one of the prettiest foods you can put on a plate.”

For sides, I tried the roasted squash with sage (using a farmers market butternut), the pickled cucumber relish, the mustard caraway vinaigrette, the baked grapefruit, roasted carrot salad with yogurt, and the mustard fig jam. The squash was nothing fancy but with sage and salt, the bite-sized cubes added a savory sweetness to the morning feast. The pickled cuke relish was a nice complement to the cool and creamy yogurt carrot salad, but was definitely too spicy to eat much of (more on that below).

The caraway mustard vinaigrette (which I served on an arugula salad with pickled beets) veered a little close to chimichurri in its heavy use of parsley and cilantro for my tastes and my attempt at the baked grapefruit (with turbinado sugar and mint) was delicious but a little soupier than the restaurant’s version. The mustard-fig jam, on the other hand, turned out quite well, and made a pleasant, hearty, and not too sweet topping on warm bread.

The real standout from my meal was the fried chicken (which, in the book’s recipe, is served in a homemade biscuit, but which I opted to eat on its own). The recipe hails from Pies n Thighs, another southern-styled cookery in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge. After making the clove, allspice, and pepper brine the day before and then brining two chicken breasts for 10 hours, it was a relief to find that the final product was totally worth the wait. The chicken was moist inside, lightly crunchy outside, and completely flavorful in its simple whole cream and egg breading under a glaze of honey hot sauce. If you have any doubts about the effect of brining, this dish will handily brush them aside.

With two rather complex new dishes under my belt (and loads of ideas for other seasonal treats), I can attest to the fact that Breakfast’s recipes work and can turn even a relatively inexperienced cook like me into a passably decent southern one. But the cookbook is not without a few issues. In several of the recipes I tried, the ingredient amounts don’t seem like they were super accurate. For example, the brine and breading for the fried chicken was easily enough for 5 times the chicken than the recipe called for. The recipe for squash called for 5 leaves of sage without really specifying how much squash (weight or volume) was used. Meanwhile, the overdose of red pepper flakes called for in the pickled cukes left them nearly inedible (and that’s coming from someone raised on fairly spicy Mexican food).

But as I stood back from the fray that my kitchen became during this road test, it became clear that the book’s goal is not to dutifully prescribe methods, spices, and amounts. Rather, it seeks to empower readers by giving us new skills to find what works for us, by helping us to know and enjoy these classic foods on far a deeper level, and by challenging our notions of what normal breakfast dishes are.

As George Weld explains in the introduction, In defense of morning, thanks to our hectic culture, breakfast is a fairly debased meal that most of us breeze through with whatever we can grab. This rush to simply fuel up in the morning leaves us at the mercy of the processed food businesses that offer options aplenty loaded with things we don’t need and devoid of the nourishment we do. But worse, this situation keeps us blind to the possibility all around us. Paying attention to the foods that grow in season near you and learning the simple and timeless ways to make hearty and delicious meals from them, can not only improve your health and energize your days, but it can begin the process of acquiring a new, more present mindfulness of life, your relationship with food, and the planet itself. With the subtitle recipes to wake up for, Weld isn’t just talking about getting up in the morning to eat better in this terrific cookbook, he’s talking about the power that cooking real food has to awaken a personal and philosophical transformation.

(Matt Bierce, 3/2/16)