There’s a received notion that American food is exemplified by the blandest of processed inventions, those rubbery slabs of “American” cheese being the epitome. By altering the standards by which the cuisine is judged – keeping the geography, but extending the history and re-coloring the inhabitants – we discover an impressive variety of foodstuffs and recipes.

Falafel from Michigan? Turns out that there’s an Arab population near Dearborn that started to boom in the early 1900s when Henry Ford told a Yemeni sailor about job opportunities. How about Marionberry Pie from Oregon? That celebrates a berry created at Oregon State University in 1948, a berry that grows in Marion County during the month of July and is too soft to export but snapped up by locals. A recipe from Montana for Bison Meatballs with Huckleberry Sauce celebrates the animal that was slaughtered to near extinction for racist reasons, now enjoying a more boutique presence as the meat is recognized as a healthy beef alternative.

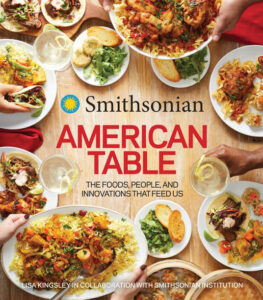

Smithsonian American Table, The Foods, People, and Innovations That Feed Us by Lisa Kingsley in collaboration with Smithsonian Institution (Harvest, Imprint of Harper Collins, New York, NY 2023) travels through time and geography to present a historical narrative that goes way beyond the standard bounds of imperialist tradition. It’s part social narrative, part recipes, interspersed with fascinating illustrations and sidebars. The dividing line for this country’s history is, of course, European colonization, but the book suggests another, later dividing line, noting, “a movement – that of food sovereignty – seeks to reclaim and return to those holistic and culturally significant foodways.” Meaning a return to the cultivation of local produce and well-raised meatstuffs.

The history tour divides North America into nine regions defined by geographic factors; thus, the Northeast spreads to Wisconsin and Illinois; the Southwest starts at Arizona and depends into Mexico to the edge of Puebla; the Great Basin surrounds Nevada and Utah and chunks of the surrounding states. And there’s a succinct page of historical culinary analysis about each of those regions.

A where-are-we-now section follows, again segmenting the country, this time into more familiar areas with a spotlight on some of its favorite dishes. New England and the Mid-Atlantic tempts you with a mouth-watering photo of boardwalk-style crabcakes while paying prose tribute to (among other foodstuffs) Connecticut’s steamed hamburgers (a phenomenon that eluded me while I was a resident of that state); Delaware’s scrapple; New Jersey’s pork roll, egg, and cheese sandwich; and, of all things, the Fluffernutter, a Massachusetts invention.

The first of the book’s recipes gives us lobster rolls from Maine – with its history as well. On to the South (look at those crawfish!), the Southeast, the Midwest (falafel gained its foothold in Michigan thanks to Henry Ford), the Southwest, the Mountain West, and the Far West and Pacific, home to Oregon’s ultra-local Marionberry Pie.

Now that we’ve got the country in place with that tour of those places, a more detailed cookery history begins. The emphasis is on immigration, the defining factor in a young country’s recipe evolution. Slaves brought with them seeds and plants and a talent for adapting local ingredients to their own styles of preparation, resulting in such hybrids as jambalaya and gumbo. Railroad development brought an influx of Cantonese workers, who also opened restaurants. “In 2009, there were more than 45,000 Chinese restaurants in the country – more than all of the McDonald’s, KFCs, Pizza Huts, and Wendy’s put together.” The one-two punch of Covid-19 and anti-Asian bias caused 233,000 Asian-American businesses to close, many restaurants among them.

Jewish food carved its own niche; Mexican immigrants brought a vital cuisine that evolved as it crossed into Texas, becoming increasingly diluted as it moved north. But Gustavo Arellano, in his book Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America, defends the result: “We must consider the infinite varieties of Mexican food in the United States as part of the Mexican family– not a fraud, not a lesser sibling, but an equal.” (This quote is quoted in Smithsonian American Table.)

What’s perhaps the epitome of a watered-down imported cuisine is celebrated in a sidebar describing the culinary journey of Ettore Boiardi, whose Cleveland restaurant Il Giardino d’Italia, which opened in 1924, was so successful that his take-out business soon overtook the restaurant. His legacy lives on today in whatever it is that inhabits cans of Chef Boyardee. And it’s not just geography here. The book takes us through Prohibition, the Great Depression, the rise of soul food, the influence of women during World War II, and much more, with a nod given to phenomena like food trucks.

Food Fads and Trends is my favorite part of the book because it allows us to revel in the backyard barbecue, marvel at the too-sweet compote that is ambrosia salad, and enjoy a variety that includes jell-o molds, fondue parties, and Oreo cookies. Homegrown wine and beer are celebrated, as are cheese-making, fermentation, and hot sauce. And there are recipes for granola, sauerkraut with caraway seeds, mozzarella (pictured in a caprese salad), and a sriracha-style sauce.

There are people behind the innovations, and the final chapters of this book celebrate them, known and (almost) forgotten. George Washington Carver is the lead-off, and you’ll find yourself lingering over the recipe for spiced sweet potato-peanut soup. Rural America lacked electricity as the Depression intensified, so the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 sought to change that. Illinois-born Louisan Mamer became the face of this movement, traveling the country to show local women how electricity could improve cooking. Korea-born Ilhan New co-founded La Choy in 1922, soon changing the face of supermarket shelves. And Irving Naxon, born in New Jersey to Lithuanian immigrants, invented the Crock-Pot in 1936. Many more such innovators are described here, and then we move on to the Taste Makers.

You know many of them. Fannie Farmer, for instance, “the mother of level measurements,” whose pre-eponymous cookbook first came out in 1896 as The Boston Cooking School Cook Book. Irma S. Rombauer was known in her hometown of St. Louis as, at best, a mediocre cook, but the suicide of her husband in 1930 launched her into a panicky search for income. She wrote and self-published a cookbook the following year in the pages of which she imparted a sense of fun. The Joy of Cooking has now gone through many revisions and sold over 20 million copies. It’s the book that taught Julia Child how to cook, and she went on to teach the world. Mastering the Art of French Cooking sits on my shelf right alongside three editions of Rombauer’s magnum opus. James Beard, Joyce Chen, Alice Waters, and Mollie Katzen are among the others celebrated here, and each of the biographies is followed by a toothsome recipe or two.

This very readable book is many things in one. It’s history, it’s social commentary, it’s a new way to consider geography, it offers a fresh way to consider American history. It’s biography, it’s a marvelous array of photos and other images – and it’s a huge variety of recipes, each of them illustrated with a mouthwatering photo that will send you to your kitchen to get started on one of those dishes. And you’ll see that, in so many respects, you’ll get to know this country and the food you eat much, much better.

(B. A. Nilsson, 6/8/23)