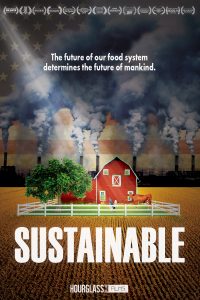

As a term of social import, sustainable, like so many politically charged buzzwords, threatens to blur into non-specificity. Sustainable, the documentary by Matt Wechsler and Annie Speicher, seeks to re-focus the term into a term of art. And they do so by making the best kind of argument in favor of a social ideal: a look at its successful implementation. Sustainable won the 2016 Accolade Global Humanitarian Award for Outstanding Achievement.

As a term of social import, sustainable, like so many politically charged buzzwords, threatens to blur into non-specificity. Sustainable, the documentary by Matt Wechsler and Annie Speicher, seeks to re-focus the term into a term of art. And they do so by making the best kind of argument in favor of a social ideal: a look at its successful implementation. Sustainable won the 2016 Accolade Global Humanitarian Award for Outstanding Achievement.

Wechsler and Speicher are the creative talents behind Hourglass Films, which also produced the Emmy-nominated documentary Different is the New Normal, Living A Life With Tourette’s (2012), which was shown on PBS, and Right to Harm, A Public Health Crisis Too Big To Ignore about the health effects of factory farming on rural Americans, which premiered in 2019.

Acclaimed chef Rick Bayless opens the award-winning Sustainable, asking simply, How am I going to make great food if I don’t have any connection with the people who are growing that food? Bayless, host of the Emmy Award-winning PBS series Mexico: One Plate at a Time, has famously made a point of working with local suppliers in his Chicago-area restaurants.

It’s one of those suppliers who is the focus of the next ninety minutes. Marty Travis and his family own and operate Spence Farm, a 160-acre farm about two hours southwest of Chicago. He’s the seventh generation of his family to work the farm; with his son, Will, alongside him, there are eight generations in the fields. Twenty years ago, Marty returned to a family property that had been factory-farmed for many years and then left fallow. He applied an eco-responsible approach that has turned his farm into something both profitable and exciting, and the film follows his family and farm through a cycle of the four seasons, reminding us of the seasonality of all these efforts.

As we look at the spring planting, Travis is reminded that he made his entry into marketing his own product by selling ramps, which grow plentifully on the property. He sold them through a chef’s consortium, and when he ran out of ramps, he asked the chefs to tell him what they’d like, and, I told them, we’ll grow it. We’ll grow as much variety as we possibly can. He delivers to thirty or more restaurants each Wednesday after confirming via email their orders. It’s more than just selling things to them. They’ve really become our friends, he says.

Marty and family founded Stewards of the Land in 2005, a cooperative that now includes some twenty area farms selling meat and produce to local chefs. They get one email from us, says Marty. And they’re guaranteed chemical-free products.

Part of what’s making this a success is his respect for the soil, and, where Travis goes, the documentary goes farther, illuminating Marty’s approach with the vision of experts. David Montgomery, for example. “We’re treating soil like dirt,” says Montgomery, who is Professor of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle (and whose books Growing a Revolution, Bringing Our Soil Back To Life; The Hidden Half of Nature, The Microbial Roots of Life and Health (co-authored with Anne Biklé ); and Dirt, The Erosion of Civilizations we have reviewed in the past). Montgomery adds: The only proof we need is in the failure left behind by the progression of societies that have damaged and degraded their soil.

His points are echoed by food writer Mark Bittman, who notes that the common perception of farming is what everyone did fifty years ago, a system based on the questions, How can we make agriculture into the most efficient profit-making system that we can? and How do we make the most possible money? Rather than, How do we produce the most appropriate food? Bittman dials in another key ingredient of the current dilemma: Agriculture is the number-two culprit in climate change.

We’re shown the results of testing at the Pennsylvania-based Rodale Institute, where CEO Jeff Moyer and Executive Director Mark Smallwood present results illuminated by animations. Rodale has been around long enough to have proven that organic, soil-healthy growing techniques result in no loss of yield compared to conventional farming, a model they promote despite much pushback from those promoting the industrial model. They’re also keen proponents of fighting climate change through agricultural reform.

Acknowledging that most American farms are planted in corn and soybeans, chef Dan Barber notes that No farmer goes out there planting corn and soy rotations because they love corn and soy. I don’t know any farmers who do that because they want to. What I’ve met is farmers who do that because the whole system is geared to corn and soy. So, as a chef, I feel the responsibility to create something so delicious so that you create a market for it. At his restaurant Blue Hill in New York City’s Greenwich Village, he created a dish called Rotation Risotto, a corn-and-soy compote that looks enticingly appetizing using corn and soy grown on the restaurant’s own farm (a playful rejection of industrial ag’s commodity corn and soy). Barber notes: It’s the nose-to-tail eating of the farm. A chef – and ultimately a culture – can play a huge influence on a system of agriculture that can sustain itself.

John Ikerd, a professor emeritus at the University of Missouri, spent many years as a proponent of the industrial food system that he now inveighs against. We certainly didn’t anticipate that the food we’re producing with that industrial food system is not healthy, wholesome food. (But now) it’s making people sick. There’s a whole range of health issues that are going through the ceiling in terms of costs and incidents that are related to the American diet. You can track those back to when we began to industrialize agriculture.

Knowing this, why do we continue to poison ourselves with unhealthy food? John Stanton, professor of food marketing at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, explains. Packaging is where the excitement is, so you’re seeing more persuasive marketing on those packages. Certain concepts like gluten-free being proclaimed on products that never have contained gluten, or the ill-defined all-natural. As Stanton observes, Cyanide is natural.

As we continue to return in the film to Travis’s farm, there’s a hint – but only a hint – of conflict. Marty’s wife, Kris, says wryly, Marty gets out of a lot of stuff he doesn’t like, echoed by Will’s comment that Dad likes to spend his time on the phone. And that – and an unspecified tractor problem – are about it for anything less than an idyllic view of this farm. Although the filmmakers admirably seek to present a valuable model, they go a little too far in their evangelizing, with an abundance of pretty sunsets and colorful flowers and not a whiff of the backbreaking toil needed to made a small farm operation work. The film also falls victim to the plague of sound-alike documentary music wherein tinkly piano and stress-free strings impose a measure of emotional sterility.

But practical lessons abound. Marty’s work with Chicago-based baker Greg Wade means that Wade’s Publican Quality Bread can provide loaves based on the oats, spelt, and heirloom wheat that Marty grows and mills for him. As Dan Barber tells us, Grains are 75 percent of our agriculture. The western world was built on wheat, but now we grow very few varieties, and what we do grow has no flavor or nutritional value.

Eli Rogosa founded the Heritage Grain Conservancy to preserve and promote landrace (pre-hybridized) wheats. Unlike the big-ag growers, she seeks genetic diversity in her fields, the better to protect her crops from pathogens. Klaas Martens is growing her einkorn wheat at his Penn Yan farm in upstate New York, Lakeview Organic Grains, and notes that Every agri-nomic problem that we face on our farm has a solution that comes in a jug, costs money, and is poisonous.

Marty also raises American Guinea hogs, a once-popular breed that serves his needs for selling tasty pork from animals that enjoy an excellent quality of life, which brings us to the issue of meat production, another huge environmental, social, and philosophical issue. Nicolette Niman, author of Defending Beef, hopes that her own efforts – she’s raising cattle with her husband, Bill – will grow into more than a niche: We want to change the way that people are eating in the United States today.

Bill Niman founded Niman Ranch in the mid-1970s to provide grass-fed, humanely raised meat to restaurants and consumers, famously becoming the supplier of pork to the Chipotle chain. But it was a money-losing operation. By the time Natural Food Holdings bought a controlling interest in 2006, Niman Ranch was $4 million in debt. Bill left the company a year later because it fell into the hands of conventional meat and marketing guys as opposed to ranching guys, and he and his wife now operate the much smaller BN Ranch (he’s not legally allowed to use his own name on his product any more, and Niman Ranch is now owned by Perdue). At BN Ranch, the cattle is raised entirely on grass, which, Bill observes, is the best possible way to sequester carbon. [More recently after the release of the film, Niman sold BN Ranch to the meal kit company, Blue Apron.]

Sustainable presents a long succession of inspiring words and examples, but the most inspiring may be those of John Kempf. He is a 32-year-old Amish farmer who, as a teenager, took on the task of rescuing his family’s Ohio farm from a losing battle against pests and disease. Kempf quickly realized that the chemicals intended to treat the problems actually were exacerbating them. His research – and successful results – led him to found Advancing Eco Agriculture, a consulting business that has made him a lecture-circuit celebrity. Our soils have become too degraded, he says, so our plants have become unhealthy. He uses sap analysis to determine what’s usually both an excess and deficiency in the suffering plants, and tailors solutions. My dream is that these regenerative models become the mainstream models around the world. And that’s when we’ll truly be sustainable.

(B.A. Nilsson, 1/12/20)