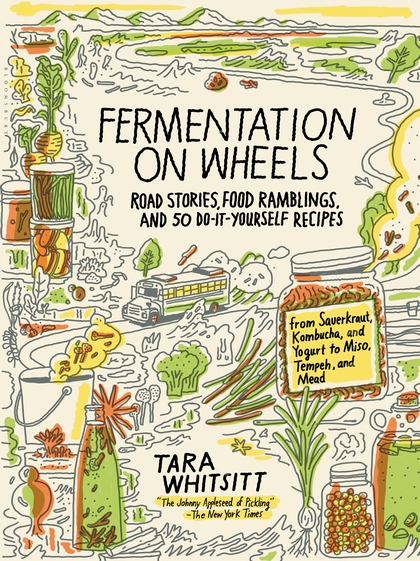

Late last year, in our book review of Tara Whitsitt’s Fermentation on Wheels, we noted that a daily dose of something fermented, like delicious sauerkraut, dill pickles or sourdough pancakes, will help get and keep a healthy gut-biome going. And earlier this month, in our review of The Hidden Half Of Nature, The Microbial Roots Of Life And Health by David R. Montgomery and Anne Biklé, we shared the almost incomprehensible news that there are some 1030 microbes on Earth – that’s a nonillion of them – and they’re everywhere, including deep within us.

It’s become clear that microbes should be our friends, with our health maintained through a microbes-driven balancing act. Instead, we are a nation in far poorer health than we were even a half-century ago: By feeding ourselves food that has been processed to an unhealthy degree, or eating food grown in such poor soil that it’s devoid of beneficial microbes and micronutrients – copper, magnesium, iron, and zinc.

Our local pharmacies and many supermarkets have responded by offering shelves full of “probiotic” supplements, with manufacturers proclaiming that their products contain billions of live bacteria. In a recent article in Bostonia (Winter-Spring 2018), Gut Check, Researchers test the probiotics in food and supplements by Kate Becker, Boston University undergrad students and Sandra Buerger, a Boston University College of General Studies lecturer, received funding from the Boston University Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching & Learning to answer the question whether the manufactured supplements actually contain what the labels promise, and how they compare to fermented foods, which are also teeming with microbes.

So far, their preliminary results, which they hope to publish in the future, line up fairly well with what’s advertised on the pill bottles. The numbers from our methods have been a little lower than what’s claimed on the box, says Buerger, but there are definitely living bacteria in there.

Buerger decided to test the manufactured probiotic pills against popular fermented drinks that naturally contain good bacteria. She started with miso soup (made from fermented soybeans) and apple cider vinegar (fermented apple juice), then added kombucha, a fermented tea. Buerger and undergraduate students, Alexander Smith (Boston University College of General Studies ’19) and Yemi Osayame (Boston University College of Arts and Sciences ’19) repeated the process (also used to test the pills) of plating samples and growing bacteria.

While the bacteria from the pills colonized tidy white circles, the dishes plated with fermented foods bloomed in colorful, disorderly splotches. Buerger suggests that it might give fermented foods an edge over the more homogeneous drugstore probiotics: A healthy collection of gut bacteria is not one type of bacteria. It’s many types of bacteria, so there could be potential health benefits of having more variety. It’s also possible that the diversity could help the bacteria thrive which will be the subject of further research. According to Buerger, Bacteria interact with each other all the time. Some of those relationships are antagonistic, but other times they talk to each other and cooperate.

(Frank W. Barrie, 3/23/18)