Wendell Berry has been the conscience of rural America for several decades, presenting a cohesive, considered response to the over-industrialization of our lives. He has done so through his essays, novels, and poetry, while living a life as a Kentucky farmer with a deep connection to the land that allows him to put his beliefs into practice.

Wendell Berry has been the conscience of rural America for several decades, presenting a cohesive, considered response to the over-industrialization of our lives. He has done so through his essays, novels, and poetry, while living a life as a Kentucky farmer with a deep connection to the land that allows him to put his beliefs into practice.

In the fall of 2016, Wendell Berry and his colleague Wes Jackson delivered the annual E.F. Schumacher lecture at the Mahaiwe Theatre in Great Barrington, the cultural heart of the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. Their analysis of our perilous state was provocative.”What screwed us up,” Berry said, “was oceanic navigation, because it taught us to think that if we didn’t have it here we could get it somewhere else.” Commitment to a community and a place is necessary in Jackson’s words “for affection to grow and intelligent action to take place to address what is needed in a community.”

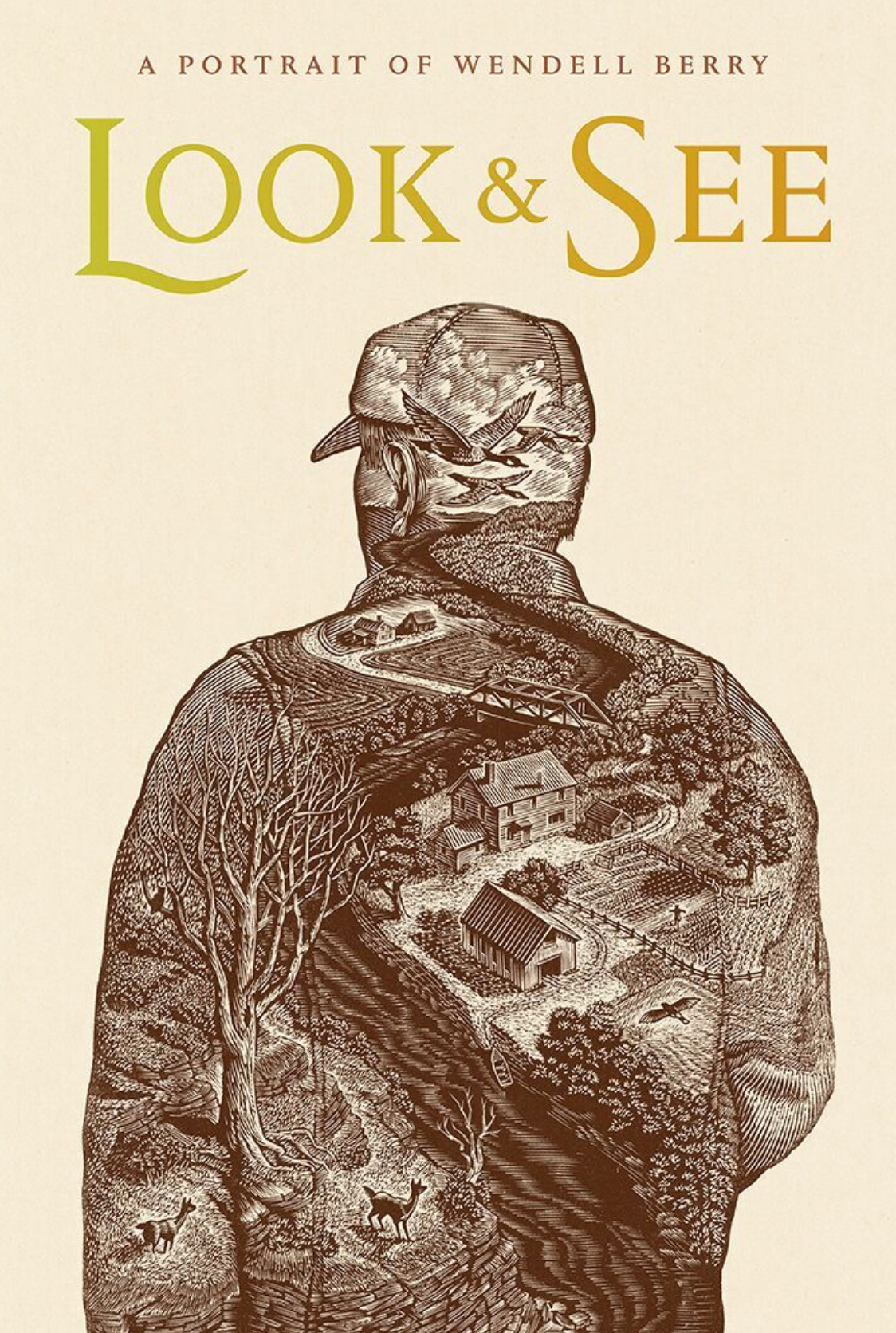

This 2016 appearance in the Berkshires raised expectations for a long-awaited documentary devoted to Wendell Berry, Look & See, A Portrait of Wendell Berry, from Executive Producers Robert Redford and Terrence Malick. Retitled from The Seer because Mr. Berry expressed misgivings about being identified in the office of prophet, it was anticipated that the film would provide a means for introducing Wendell Berry to a much wider audience, not just his many admirers.

However, it’s a disappointing portrait. As Berry refused to be filmed, it lacks his presence at its center. I don’t doubt that this was prompted by his modesty, but it leaves a vacuum that’s not filled by the affectionate descriptions coming from family and friends. Daughter Mary, an effective speaker, probably deserves her own documentary. As founder and executive director of the The Berry Center, she finds practical solutions for the problems her father’s essays explore. And Steve Smith, her husband, offers a farmer’s persuasive voice to the movie.

Look & See is the second full-length documentary from Laura Dunn, whose The Unforeseen from 2007 looked at an ill-fated housing development near Austin, Texas, and drew from Berry’s writing for its soundtrack. Her new film suffers overall from what’s become a familiar documentary style, with limited-length segments tied together by voice-overs that have an affected piety, very different from Wendell Berry’s unforced and unaffected, yet passionate, voice and presence experienced at the 2016 lecture in the Berkshires or at his 2012 Jefferson lecture sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

Fortunately, some of the spoken material is Berry’s poetry, read by the author, including his poem A Timbered Choir, with its epochal vision of urban intrusion, used at the movie’s start. But this well-known Berry poem is accompanied by quick-changing images of urban life, robbing the words of their impact by their distracting frenzy. And the piano music by Kerry Muzzy, that sounds throughout much of the film, is new-agey finger-wandering that also distracts and has a dulling effect.

Farmers whose lives continue to be ruined by industrialization offer unsurprising assessments of their plights, but it’s dismaying to see tobacco farming as the prime example here. Yes, it’s a huge Kentucky crop, and Berry’s readers know that his family has farmed it for generations. But it’s also a reminder that one of Berry’s weakest essays is The Problem of Tobacco, collected in the 1992 volume Sex, Freedom, Economy, and Community. His arguments in defense of the crop are flawed, as when he notes that tobacco’s opponents will sit in their large automobiles, spewing a miasma of toxic gas into the atmosphere, and will sit in a smoke-free bar, drinking stingers and other lethal beverages (note the effectiveness of the adjectives large and lethal), thus succumbing to the fallacy of false equivalencies.

All of which contributes to the discomfort of seeing lovingly photographed tobacco harvesting and storage. We learn that Steve Smith moved away from tobacco – It lost its beauty, he says. It lost its appeal. It was no longer farming: it was something industrial – to raising and selling food crops at markets and through a CSA (community supported agriculture) farm model, and the film’s final section amplifies that approach – the most hopeful note this movie sounds.

Archival footage of Berry debating former Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz in 1974 gives a look at the beginnings of Berry’s crusade. Butz aggressively promoted industrial-scale farming, urging farmers to adapt or die. Those who cling to the moldering past are the ones who die. Butz (whose political career came to an ignominious end) embodied the arrogant profiteering that has gone on to gut farming, so it would have been fascinating to see more of the Berry-Butz exchanges.

But this movie is mining emotional reactions without earning them through considered argument. We’re moved by shots of glinty sunsets, by point-of-view treks along country pathways with a country dog – a claim to a wistful nostalgia for something remaining undefined. But I fear that Look & See does Berry a disservice by presenting him as a cranky Luddite, condemning of all technology and urban life.

There are loving close-ups of a Smith-Corona Secretarial, which, we assume, is the manual typewriter Berry continues to use (he has declared that he’ll never buy a computer). His best essays – and there are many – are excellent indeed, and his public appearances prove him to be a persuasive speaker. But far too little of that makes its way into this film. We see instead hand-set metal type locked into a chase for platen-press printing, which is how some of Berry’s poetry is published, but it comes across, in this context, as too recalcitrant, too precious, and therefore a metaphor for the movie at large. If you’re already a Wendell Berry admirer, Look & See may be a pleasant enough diversion; if you’re just getting to know the man and his work, look elsewhere.

(B.A. Nilsson, 2/1/18)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): A good introduction to Wendell Berry’s writings is his novel, Jayber Crow, a Life on the River, a powerful portrait of a fictional barber of a small Kentucky river town, which describes the collapse of a small town way of life, close to nature and its replacement with a new society tied to the rush of the interstate and a system of industrial agriculture heedless of the environment and the past. And check out some wonderful and rare photographs of Wendell Berry illustrating Brian Barth’s Wendell Berry Is Not a Prophet which appeared in Modern Farmer (10/23/17).]