The natural fermentation (or pickling) of real food, such as cabbage, cucumbers, carrots and beets has become a big part of the good food movement. And Tara Whitsitt’s Fermentation On Wheels is Exhibit A in proving that tasty food, sustainability and community building is the inspiriting consequence of spreading knowledge about pickling food. The fermentation process, which depends on naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria to preserve nature’s bounty as tasty sustenance long after harvest season, is succinctly described by Whitsitt as a testament to the deep intelligence of age-old processes.

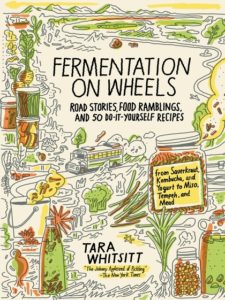

The recently published account of Tara Whitsitt’s life on the road across the United States in her 1986 International Harvester bus turned fermentation lab, Fermentation On Wheels, Road Stories, Food Ramblings, And 50 Do-It-Yourself Recipes from Sauerkraut, Kombucha, and Yogurt to Miso, Tempeh, and Mead (Bloomsbury, New York, NY, 2017) is a very personal narrative, much like a revealing memoir. In addition, it’s full of sharp insight into the depressing state of the American food system with industrial agriculture’s tight grip on farmland.

Whitsitt has a profound understanding on how massive amounts of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides are harmful to the rich soil that is America’s major natural resource and on our bodies. And her 50 recipes (conveniently indexed on two pages at the end of the book) are easy to follow and confidence building for a cook attempting to ferment the bounty of nature, making her narrative as much a cookbook and guide to fermentation (complete with Whitsitt’s own illustrations) well worth having handy in the kitchen.

This Jack Kerouac of the fermentation world (as nicknamed by David Leite of The Splendid Table) visited dozens of organic farms, homesteads, communities, and activist spaces intent on raising awareness of the lost art of fermentation and the spirit behind it. I read her account with increasing awe at the grassroots movement that has bubbled up like a sourdough starter to offer a roadmap to better health in our bodies and communities. Whitsitt’s work has helped to restore her own understanding of the wonder of farmland and the working of it. In her words: To have a connection to and understanding of food and land now, through growing food, fermentation and communal feasting, made me feel that I was in on an old family secret.

Inspired by a recurring dream and supported by Heart and Spoon, her home community in Eugene, Oregon, Whitsitt decided to mobilize her talents and share them with anyone willing to learn. Her fantastic tale of taking to the road is prefaced with all you need to know about fermenting, with the first chapter focusing on fermentation basics, including why one should ferment and what supplies you’ll need. She makes it easy and clear, including charts like her salinity table, which could inspire even the most hesitant cook to give it a go. For those of us already familiar, she provides plenty of technical terms to bring out the geek in us without bogging down her story in science or making the reader feel intimidated.

While intrigued by some of the more complex ferments, like fermented green tea salad or black eyed pea fritters, I decided to prepare some of the simpler recipes in Fermentation on Wheels. I can say that preparing Whitsitt’s recipes for kombucha, sauerkraut, dill pickles, and sourdough pancakes was fun and a pleasure to share with friends. As an initiation in the art of fermentation, give her classic sauerkraut recipe a try. A daily dose of something fermented, like this delicious sauerkraut, will help get and keep a healthy gut-biome going! You might even be tempted to make up a batch of Whitsitt’s sourdough pancakes (a favorite potluck item for her as well as a tasting option for youth fermentation classes) and follow her lead: She likes to roll sauerkraut into a pancake and eat on the go.

Classic Sauerkraut

Yields 1 gallon, 1-4 weeks

Ingredients

7 lbs cabbage (2 medium-sized heads)

2 tbsp caraway seeds

1 tbsp juniper berry

2-3 tbsp salt

Materials

Gallon glass jar or crock

Weight and cover

Process

1. Cut cabbage into quarters and finely chop. Place chopped cabbage into a large bowl. If you have outer leaves of cabbage, rather than compost them, place them aside.

2. Add caraway seeds and juniper berries to the bowl of chopped cabbage.

3. Add 2 tbsp of salt and massage the cabbage for 5-10 minutes. Your cabbage will release water, which will serve as the kraut’s brine. Taste the cabbage—you may want to add more salt to your liking.

4. Check for a puddle at the bottom of your bowl and squeeze a handful of cabbage above the bowl to check whether it has produced enough brine. Once gently squeezed, brine should drip with ease from the cabbage.

5. Pack the cabbage into your gallon jar until it’s submerged below brine. Take the cabbage leaves you set aside from earlier and layer them on top of your kraut, pressing down.

6. Add weight, such as scrubbed and boiled river rocks or a small jar filled with water, on top of the layer of cabbage leaves. Secure a tea towel to the mouth of your jar with a rubber band to keep dust and bugs out.

7. Wait a week and taste—you may want to keep it going another week, but it’s good practice to try your ferments along their journey. Vegetables will ferment at different speeds depending on their environment—the warmer it is, the faster it will ferment, while the colder it is, the slower it will ferment. Most vegetable ferments thrive between 68ºF to 76ºF.

8. When the sauerkraut is to your liking, cover it with a lid and store in the fridge. Keeping your new kraut cool slows fermentation, so you can more or less enjoy the fermented flavor from when you sealed the jar.

Tara Whitsitt is getting ready to embark on the second voyage of her mobile fermentation recruitment station, as neatly described by Sandor Katz, the author of The Art of Fermentation. Whitsitt’s description of her meeting up with Katz in Tennessee, who she calls “the master of controlled rot,” is inspiring, and another reason to get your own copy of Fermentation on Wheels (if only I had three thumbs to put up in recommending this book, but two will have to do). And a further suggestion, Whitsitt’s non-profit of the same name that provides free food education and inspires people through workshops, literature, and visual art projects that raise awareness about food sustainability alongside teaching fermentation is worthy of support.

(Lucas Knapp, 11/17/17)