Farmer artist Lavern Kelley (1928-1995) and his brother Roger, neither of whom married, lived their entire lives on a 230 acre dairy and livestock farm, in the village of Laurens just outside Oneonta (Otsego County) in upstate New York, which had been their family’s farm since the late 19th century. Twenty years after his death, Lavern Kelley’s art is now on display (until 12/31/15) in a retrospective exhibit, Lavern Kelley: The Art of the Farm, at the Fenimore Museum in Cooperstown (Otsego County, NY).

Patterson Sims, the Guest Curator, in his essay accompanying the exhibit, notes that Kelley “never had any formal artistic training, nor wanted it.” Kelley’s art, according to Mr. Sims, is rooted in his “deep conviction in the fundamental verities, values, and historic centrality of farming and rural small town and community life.” It wasn’t until the 1980s when Kelley was in his 50s, that he began to understand he was “an artist,” and in 1989, his art was the subject of a solo exhibition at Hamilton College’s Emerson Gallery (now the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art). Nearly three decades later, the art of Lavern Kelley has earned this second museum show. Farmer artist Lavern Kelley also received recognition in the late 1980s when he was invited to demonstrate his woodcarving techniques at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. To do so, Kelley took his first and only train ride, traveling between Albany (a long hour’s car-drive from his Oneonta area farm) and New York City, where he flew on to Santa Fe.

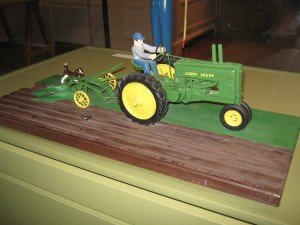

Lavern Kelley was a teenager when farming in the 1940s in upstate New York changed from horse to mechanical power, and he was fascinated, if not obsessed, with John Deere tractors. In his words: “Plowing with one of these tractors was actually an event to look forward to, whereas doing so with horses was usually, at least by me, dreaded.” Little surprise that his artistic accomplishment would include (by the mid 1970s) over 450 painted carved trucks and tractors, which he displayed in a special shed near the family farmhouse. The hundreds of trucks and tractors “in tight formation,” according to Patterson Sims, “looks like a folk art, sculptural version of an Andy Warhol Pop-Art painting with massed Coca-Cola bottles or Campbell’s soup cans.”

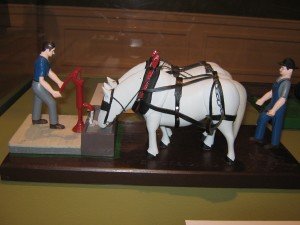

By the mid 1980s, Kelley’s subjects for his skillful wood carving had expanded from trucks and tractors to include animals (cows, pigs, horses, dogs, cats and birds) and human figures as well as farming vignettes. Although plowing with horses was “dreaded” by Kelley, one of his farming vignettes on display, A Drink Before Going to Work (1990) is a throw-back to earlier days on the Kelley farm. [In fact, horse-powered farming has become appealing of late for “small-scale, resilient farming with a closed-loop system” in the words of Stephen Leslie of Cedar Mountain Farm, the author of The New Horse-Powered Farm (Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, 2013).]

Kelley also began to make formal photographic portraits in the late 1970s, and more extensively through the final years of his life, of his carvings positioned out of doors on the farm with hand-written commentaries beneath the enlarged prints. Curator Sims observes in his essay that Kelley’s staging of photographs demonstrates a “formidable intellect, clarity, and idiosyncratic artistic talent.” Sims compares Kelley’s photography to that of William Wegman, Duane Michals, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Gregory Crewdson, who employed “photography to stage images using real and make-believe surrogates and backdrops.”

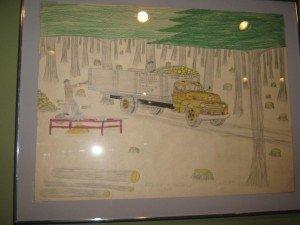

For this visitor, of particular interest were Kelley’s color pencil and crayon drawings from the late 1940s of the mindful harvesting of wood from the family farm’s woodlot. They brought to mind Wendell Berry’s novel Jayber Crow where a treasured woodlot of 75 acres of very good timber, known as the Nest Egg, was greedily clear-cut for a few fast dollars. Kelley’s drawings show no such wrongheadedness on his family farm. His words, displayed near these appealing folk art drawings, echo appealingly in this modern era of maximizing quick profits: To a farmer, a good woodlot was alway an emergency source of income when hard times hit home. The farm woodlots were loaded with lumber. My brother and I would cut it, skid it out, and sell it in the log. We cut only the trees we wanted to cut, leaving the others to grow. Whenever we sold it on the stump, they took everything.

And in this era of human snow birds flying south, the words of Lavern Kelley (rooted in his rural, upstate New York farm) on his love of winter are valued by anyone who also appreciates the changing of seasons: Winter used to be my favorite season. . . We cut wood every winter, and I loved that, then we burned wood for fuel, both for heat and to cook, so it was essential to cut forty to fifty cords each year. In the wintertime, with all the livestock we had, it took most of the day to do just the barn and hens and hog chores, so if [we] managed to cut wood for two or three hours a day, that was about all the time [we] had. The long evenings were always pleasant for me. After chores, we would have our supper, then I usually would draw pictures till bedtime.

As a closing note, in the gift shop at the Fenimore Museum, hand-cut wooden trucks by Sharon and Joseph Benesch honor the memory of Lavern Kelley. Joseph Benesch, who has been working with wood all of his life, using oak, black walnut, ash, and cherry, hand cuts, laminates and hand fits trucks together while Sharon Benesch stains and paints.

[Lavern Kelley: The Art of the Farm, September 19-December 31, 2015; Fenimore Art Museum, 5798 State Route 80, Cooperstown, NY]

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/14/15)