A little over three years ago, Trader Joe’s opened a store in the Capital Region of upstate New York. For years, a group called We Want Trader Joe’s in the Capital District, organized by Bruce Roter, a professor at the College of St. Rose in my hometown of Albany, campaigned to bring the national chain to the area. Sponsoring field trips to the Trader Joe’s store two hours away in Amherst, Massachusetts, and savvy use of the local media, Prof. Roter earned recognition in the summer of 2012 when Trader Joe’s opened in the Albany suburb of Colonie. According to the story in the Albany Times Union about the opening of the store, Prof. Roter and other members of his group, wearing T-shirts reading “We Brought Trader Joe’s to the Capital District!,” lined up with Trader Joe’s employees “as the first customers poured inside, high-fiving them and shaking hands.” (As a side note, Prof. Roter is currently campaigning for the creation of A Museum of Political Corruption in the state capital of Albany, too often in the news for self-serving politicians on the take.) Trader Joe’s store in Albany’s suburb of Colonie seems very busy and successful.

Cheap food drives the food choices of many consumers, and Trader Joe’s has established a reputation for food bargains. Its local reputation for cheap food has become so pronounced that the Albany Times Union recently ran a fascinating story, Who’s making Trader Joe’s food? An investigation of the secretive grocery chain. The reporter, Amy Graff, focused on 11 food items, ranging from organic canned diced tomatoes to mini peanut butter sandwich crackers. Her report suggests that the very successful chain sources “its own products . . . from well-known brands and sells them under the Trader Joe’s sub brands at a discount.”

Part of this website’s mission is to promote CSA farms (where a consumer purchases a share in a farm’s bounty before the growing season starts), farmers markets, and food co-ops which stress the sale of locally grown and produced real food. (And the Capital Region is fortunate to have a thriving food co-operative, the Honest Weight Food Co-op, which is one of the few left in the United States that still maintains a member labor program, recently reinvigorated by its members.) The local co-op addresses the concern of consumers for cheap food by publishing an informative, handy guide, Eating on the Cheap, Smart Ways to Stretch Your Dollars. Offering ten tips, ranging from stocking a pantry with food from the co-op’s extraordinary Bulk Department where beans, nuts, grains, flours and much more can be found, eating what’s in season and DIY (do it yourself by making by hand with a bit of preparation and know-how what we buy at the store, such as bread, beverages, cleaning products). Consequently, the Trader Joe’s food items researched by reporter Graff, mostly processed food items, don’t get my food dollar.

And there’s an important economic reason why spending food dollars at a farmers markets or at a food co-op is preferable. According to American Farmland Trust as reported earlier for every $10.00 spent on local food at a farmers market, “farmers get close to $8.00 to $9.00 of the money spent compared to $1.58 farmers and ranchers receive of $10.00 spent on food in general. Plus for every $10.00 spent at a farmers market, studies show as much as $7.80 is respent in the local community supporting local jobs and businesses. Further, the decision to spend food dollars at a food co-op rather than a conventional grocery store also makes better sense for the local economy.

According to a report, Measuring the Social and Economic Impact of Food Co-ops, issued by Co + op, stronger together which represents 134 National Cooperative Grocers Association (NCGA) co-ops nationwide, there is a much greater “local impact” when food dollars are spent at food co-operatives instead of conventional supermarkets. Purchases “locally sourced” represent 20% of purchases for food co-operatives compared to 6% for conventional supermarkets, with local suppliers averaging 157 for food co-operatives verses 65 for conventional supermarkets. Similarly, a conventional grocer spends 72% of each dollar of revenue to purchase inventory, but only 4% is spent on locally sourced products, while the average co-op spends 62% of every dollar in revenue on inventory, 12% of which is spent on locally sourced products. Co-ops spend a lower % of every dollar in revenue on inventory than conventional grocers because the wages of co-op employees average 7% higher than wages of employees of conventional grocers and co-ops employ more people, with 9.3 jobs for every million dollar in sales compared to 5.8 jobs per million dollars in sales of conventional grocers.

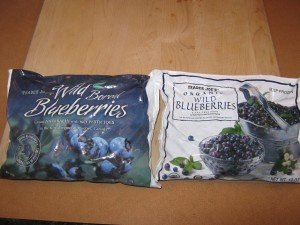

Nonetheless, on a recent visit to the local Trader Joe’s, two real food items, albeit frozen food, caught my eye, as the seasonal fruit disappears from farmers markets (though I’ve stockpiled a nice supply of organic apples and cranberries). Trader Joe’s Wild Boreal Blueberries described as “Grown NATURALLY with NO PESTICIDES in the Boreal region of Quebec, Canada” at the bargain price of $3.49 for a 16 oz. (1 Lb) package and Trader Joe’s Organic Wild Blueberries grown in Eastern Canada described as “firm, ripe berries, small in size, but big in sweet tangy flavor” at $3.49 for a smaller 12 oz package were worth some of my food dollars. They’re sure to be enjoyed in a bowl of hot oatmeal on a wintry morning. Alas, these wild or organic Canadian berries purchased at Trader Joe’s are an exception to my general rule of spending my food dollars by purchasing a share in a CSA farm’s bounty, in my case Roxbury Farm in Kinderhook (Columbia County, NY), shopping at farmers markets and at my local food co-op.

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/10/15)