Every city must have them: vacant lots where nothing grows but weeds, where the detritus from a busy metropolis blows in and collects in corners. Some people drive by those lots and see eyesores, just one more sign of a forsaken neighborhood. Novella Carpenter looked at the weedy 4,500-square-foot vacant lot in her Oakland, California, neighborhood (a postcard of urban decay ominously nicknamed GhostTown) and saw an opportunity.

She started small: with a few vegetable beds, some fruit trees, a beehive and four chickens. Then came the geese, the ducks and the turkeys. Then rabbits, then pigs. Within a few years, just blocks from a busy street where shootings were not uncommon, she had a bustling urban farm, a little slice of heaven in a rough corner of Oakland.

“In our neighborhood, there was some greenery, mostly in the form of weeds, but when you walked through the gates into what I had started calling the GhostTown Garden, it was like walking into a different world,” Carpenter writes in Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer (The Penguin Press, New York, New York, 2009). Her description of the green world she created in urban Oakland is magical:

There was a lime tree near the fence, sending out a perfume of citrus blossoms from its dark green leaves. Stalks of salvia and mint, artemisia and penstemon. The thistlelike leaves of artichokes glowed silver. Strawberry runners snaked underneath raspberry canes. Beds bristled with rows of fava beans, whose pea-like blossoms attracted chubby black bumblebees to their plunder. An apple tree sent out girlish pink blossoms. A passionfruit vine curled and weaved through the fence that surrounded the garden.

Carpenter describes the trials and triumphs of her little farm and the family history that led her down her unusual path. She’s an enthusiastic proponent of fresh food, organic farming and of helping people reconnect with their agrarian roots.

Darkly funny throughout, the book’s most amusing moments are when city meets country in unexpected ways: when the pigs escape and are corralled by inner city residents who’ve never seen a live pig before; when Carpenter and her boyfriend go dumpster-diving at ritzy restaurants for food for their livestock; when she sells a noisy rooster to the grocery store owner around the corner, over the voluble protests of his wife. The neighborhood features an array of unique characters: a transvestite running an underground speakeasy, a homeless guy living in a series of abandoned cars, a house of Buddhist monks handing out food to the needy, and a landlord and neighbors with varying levels of tolerance for the growing farm. Carpenter’s affectionate descriptions of them and her interactions with them provide some of the book’s heart.

Also funny is Carpenter’s attempt to spend one July eating only fresh or preserved food from her garden and her animals, food “foraged” in the neighborhood (but not in dumpsters), and crops she can barter for. The effort leads her to literally eat two-year-old corncob household decorations and flowers from her zucchini plants (but unlike a gourmand not stuffed with basil ricotta) and to climb onto the roof of an abandoned house to pick plums off a tree. Along with the diet’s challenges, Carpenter writes, “I would miss my intimacy with the garden. When I was eating faithfully only from her, I knew all of her secrets. Where the peas were hiding, the best lettuces, the swelling onions.”

More uncomfortable is Carpenter’s determination to slaughter and eat her farm animals. She’s raising livestock, not pets, but as she describes the personalities of various creatures — Harold and Maude, the wandering turkeys, Little Girl and Big Guy, the voracious pigs — it’s hard not to see them as characters. Carpenter is devoted to her animals, but she also wants to feel connected to her food and views their final destination — her dinner table — as their destiny. “I suppose I could come up with some lofty reasons for what had gotten me here,” Carpenter writes when she goes to an auction to buy the piglets. “To discover the American tradition of pig raising. To test my formerly resolve in the face of an intelligent, possibly adoring creature like Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web. To walk in the footsteps of my hippie parents, who had raised a few hogs in their day. “But I’m not going to lie: this was all about pork.”

She works hard to give all her farm animals happy lives and to honor them by (humanely) killing them herself or by witnessing their deaths. But, as a reader, it was hard to process one character in a book enthusiastically eat another character that just moments before had been providing comic relief. The descriptions of their deaths – ducks dispatched with tree pruners, rabbits with a garden rake – is not for the faint of heart either.

Though Carpenter offers minute and passionate details about her farming, the memoir-like book leaves some questions unanswered. Carpenter’s live-in boyfriend, Bill, for instance, reappears at intervals, but is mostly a shadow drifting around the periphery of the story. He helps her get manure or dumpster dive and enjoys eating the rabbits, but we never get a sense of who he really is.

Carpenter’s financial struggles are mentioned briefly, too, but never in detail, and the various jobs she uses to support herself – because the farm is in no way profitable — get only a line or two. Farm City offers a look at the hard work and dedication it takes to run a farm anywhere, and an intriguing glimpse at the possibilities of urban farming. If we want to know where our food comes from, Carpenter says, what better way than to grow it or raise it ourselves?

You can read more about Novella Carpenter and her urban farm on Carpenter’s entertaining and informative blog. She is also the co-author with Willow Rostenthal (an urban farmer and the first director and one of the founding farmers of West Oakland’s City Slicker Farms) of The Essential Urban Farmer (The Penguin Press, New York, New York, 2011) and a very personal story, Gone Feral: Tracking My Dad Through the Wild (The Penguin Press, New York, New York, 2014), available as of August 2015 in paperback format, of her “effort to connect with her long-estranged septuagenerian father, a homesteader, classical guitarist and war veteran whose views on freedom prompted a life of solitude” (the description of Carpenter’s recent memoir in the Albany, N.Y. Public Library’s catalogue).

Gillian Scott (8/6/15)

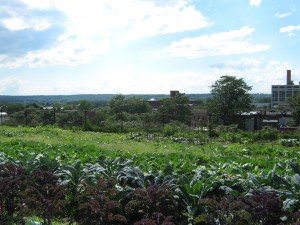

[Editor’s Note: Capital Roots, a community organization in upstate New York’s Capital Region, which began the area’s Community Gardens program, now feeding 4,000 families in Albany, Rensselaer, Schenectady and southern Saratoga counties, also operates (i) the Veggie Mobile (Produce Aisle on Wheels), which delivers fresh produce directly to 1000s of elderly, low income and disabled residents, (ii) a regional food hub in its new headquarters aptly named Urban Grow Center and (iii) the Produce Project which provides dozens of high school youth access to educational and employment opportunities each year in an urban agricultural training program focused on sustaining the bountiful harvests of an urban farm on a hill overlooking downtown Troy (Rensselaer County). The photos illustrating this review of Novella Carpenter’s Farm City are of Capital Roots’ urban farm in Troy, NY.]