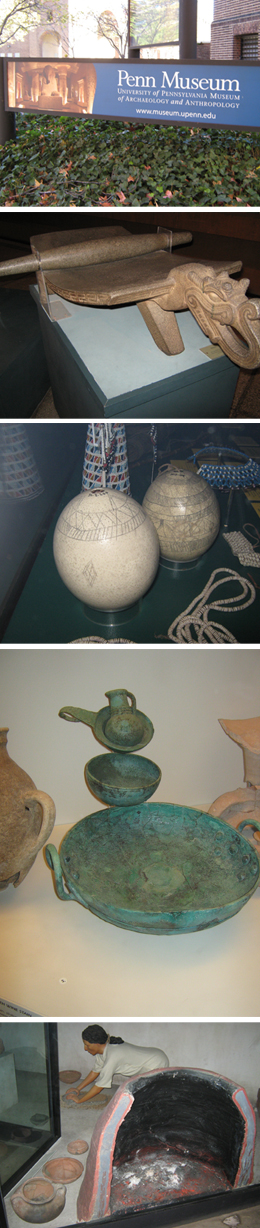

Founded in 1887, Philadelphia’s University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (better known as the Penn Museum) has three gallery floors with art and artifacts from all over the world. This extraordinary institution has conducted more than 300 archaeological and anthropological expeditions, and Penn archaeologists and anthropologists are still exploring, excavating, and researching around the world today. The museum’s collection is staggering: briefly described in a Penn Museum brochure as “materials from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Canaan and Israel, Mexico and Central America, Asia, and the Mediterranean World, as well as artifacts from the native peoples of Africa and North America.” There are 20,000 objects in its African collection and 42,000 artifacts in its Egyptian collection alone.

Founded in 1887, Philadelphia’s University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (better known as the Penn Museum) has three gallery floors with art and artifacts from all over the world. This extraordinary institution has conducted more than 300 archaeological and anthropological expeditions, and Penn archaeologists and anthropologists are still exploring, excavating, and researching around the world today. The museum’s collection is staggering: briefly described in a Penn Museum brochure as “materials from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Canaan and Israel, Mexico and Central America, Asia, and the Mediterranean World, as well as artifacts from the native peoples of Africa and North America.” There are 20,000 objects in its African collection and 42,000 artifacts in its Egyptian collection alone.

An afternoon’s visit, which could have been an unfocused and overwhelming experience, became a stimulating couple of hours by following a suggested “Culinary Expedition” self-guided tour. An informative and easy to follow brochure, available at the main entrance where admission tickets are sold (Students with College ID, $10; Adults 18-64, $15; Seniors 65 and above, $13) gives a wonderful taste for the museum’s offerings and sends the visitor through nearly all of the galleries on the three floors.

The “Culinary Expedition” focuses on a dozen well-chosen artifacts and provides the visitor with a tangible way to think about the diets of ancient human ancestors as well as of native peoples of Africa and North America. The first two objects on the tour are wooden cooking paddles of two distinct native peoples of North America. A wooden “Mush Paddle” (circa 1920), with a cornstalk and beaver design on its handle, is typical of those used to make corn soup by the Delaware/Lenape and Munsee nations of eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. It’s easy to visualize the paddle stirring a pot of soup or stew made with green corn and the meat of small game animals. The other is a wooden “Acorn Mush Paddle” (circa 1900) used in the Pomo culture of Northern California where acorns were a food staple. Highly nutritious and abundant, acorns were dried, then ground into acorn flour which was then mixed with water to create a thin soup. The paddle was used to stir the hot rocks added to cook the soup. Also included on this first stop in the gallery, “Native American Voices: The People- Here and Now”, is a shallow, open rimmed “Winnowing Basket” (circa 1890) used by the Akimel O’odham/Pima people of Arizona to toss harvested grains into the air so that the chaff- the lightweight, protective casings of rice and other grains- is blown away. The beauty of this basket provides an easy explanation why “baskets have since become a tourist commodity.” (Seeing these Native American artifacts is a reminder that a meal at Mitsitam Native Foods Café, the wonderful café at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, should be on the to-do list of any visitor to or resident of Washington, DC).

The next stop in the Mexico and Central America Gallery focuses on a grinding stone more than 1000 years old (circa 200-800 CE). This finely carved Chorotegan (prehistoric farmers of lowland Costa Rica and Nicaragua) “mano [hand stone tool] and metate [large stone surface]” made of basalt was used to process grains and seeds during food preparation by a horizontal, rolling motion rather than the vertical pounding method of many mortar and pestles.

Water containers in the Africa Gallery are the next focus of the tour and they are stunning, hollow ostrich egg shells (circa early 20th Century). Used during the wet season in Southern Africa, San people (also known as Bushmen) would fill hollow ostrich egg shells with water, seal and systematically bury them. One hollow ostrich egg filled with water can weigh up to three pounds and provided significant hydration when retrieved in the dry season, allowing Bushmen to survive where other cultures could not. [Survival, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, has an active campaign to protect Africa’s Bushmen of Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Preserve.]

The remaining artifacts on the tour are all ancient materials “Before The Common/Current/Christian Era” (BCE), terminology used by the Penn Museum. and many academic and scientific publications, as an alternative to BC (Before Christ). In the Greece Gallery which displays many coins of Greek cities, the tour focuses on a silver coin featuring an ear of barley (circa 520-500 BCE). This coin “probably celebrates the agricultural wealth of the Greek colony of Metapontum, Italy” by depicting this nutritious grain which was a staple food for Roman gladiators who “ate enough to earn the nickname of hordearii, or barley-eaters.” Also on display in the Greece Gallery is a red bull’s head rhyton, a drinking cup (circa 350-320 BCE) from the Greek city of Tarentum in ancient Italy, that has a handle but no base so that it cannot be set down until it’s empty. Easy to imagine the red bull’s head rhyton full of wine, and no surprise, with the universal appeal of wine and intoxication, that the culinary tour next focuses on a bronze strainer set (circa 1200 BCE) to decant wine (displayed alongside a juglet and a drinking bowl) in the Canaan and Israel Gallery. Decanting wine is an ancient concept whereby younger wines are made to taste better by increasing oxygen exposure, and according to the “Culinary Expedition” brochure, “this transitional Late Bronze-Iron Age set could filter sediment and probably grapes, raisins, and grape stems.” Even in the Bronze Age, regional variations in wine (as well as olive oil) were recognized and valued. Wine, the Royal Drink, and olive oil, the Queen of Trees, were the agricultural products with the greatest commercial value: common food items but also associated closely with wealth, status, religious ritual.

Also on display in the Caanan and Israel Gallery is an ancient bread oven. Usually made from clay coils or from re-used pottery jars, the oven was heated in the interior using dung for fuel. Flat breads were baked against the interior side walls. According to the notes in this gallery in front of the diorama, “Bread: The Daily Grind,” bread making was undertaken almost every day and was one of the main activities of a household. People in Canaan and Ancient Israel consumed between 330 and 440 pounds of wheat and barley per year, with individuals typically consuming 50-70% of their calories from these cereals- mostly eaten in the form of bread. The grain was ground on a coarse surface to break down the soft center of the kernel into flour with basalt, a volcanic stone, preferred for this process because of its rough surface and relatively light weight. It is observed that the Chorotegan”mano and metate” (grinding stone), noted above, from Central America, far from the Middle East, was also made of basalt.

The next stop is in the gallery, “Iraq’s Ancient Past,” and a viewing of the oldest artifact in the tour: a cylinder seal (circa 2500-2450 BCE). Cylinder seals invented around 3500 BCE are small round cylinders (typically about one inch in length and engraved with written characters and figures), and were used in ancient times to roll an impression onto a two dimensional surface, generally wet clay. This cylinder seal on display on the tour, more than 4500 years old, was found in the Great Death Pit in ancient Iraq and likely “depicts a banquet for one of the women in the Great Death Pit, found holding a silver tumbler close to her mouth.” Made of lapis lazuli (a deep blue semi-precious stone prized since antiquity for its intense color), it depicts a festive scene with dancers, musicians, and revelers sipping beer through long straws. A brief detour from the culinary expedition was made to view some of the other ancient objects in this gallery, which tells the story of the discovery and excavation of the Royal Cemetery at Ur in modern-day Iraq. This visitor was fortunate to see the extraordinary Lady Puabi’s headdress and jewelry (circa 2650-2550 BCE) on its last day on display at the Penn Museum before it is loaned to the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University.

In the China Gallery, the tour focuses on a bronze wine vessel (circa 1600-1046 BCE) from the Shang Dynasty though the brochure suggest that it “was probably used to store a beer-like drink made of fermented grain, not grapes,” probably millet, a staple grain of ancient China. The fermented beverage may have been similar to a modern type of Chinese beer called huangjiu, also known as “yellow wine.”

The tour concludes with a final stop in the Upper Egypt Gallery to view artifacts depicting the mild-flavored tilapia (which has become the fourth most eaten seafood in today’s United States). The objects (circa 1539-1075 BCE) include a faience bowl (made from powdered quartz, not clay) with a tilapia decoration, a small calcite dish (made from a carbonate mineral, not clay) in the shape of a fish, and a green faience tilapia rattle “that may have been used to play music.”

Tied into this stimulating “Culinary Expedition” is a unique and informative cookbook masterminded by the Penn Museum’s Women’s Committee, whose mission is “to stimulate interest in the Penn Museum’s research and educational programs.” The Committee achieves that and more with its Culinary Expeditions, A Celebration of Food and Culture edited by Expedition Magazine Editor June Hickman, Ph.D. (The Women’s Committee, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, 2014) which incorporates beautiful photographs of many of the artifacts on the tour including the wondrous ostrich egg shells used as water containers, the tilapia rattle, the bull’s head rhyton, the silver coin with the barley grain design, and the ancient grinding stone. Recipes, organized in eight geographical/cultural categories, complement the path taken by the culinary expedition: Africa, Asia, Egypt,Greece, Mesoamerica, Middle East, Native America, and Rome. More than a few of the recipes (developed by over 60 “recipe contributors and testers”), caught this visitor’s attention as must-try: avgolemono (Greek lemon rice soup), braised carrots with kalamata olives, hot chocolate (Mexican type), whole wheat pita bread, beets & yogurt salad, wild rice salad with fruit and nuts, and blue corn pancakes. The ten recipes grouped in the Africa section, follow a two-page narrative that provides a concise and insightful overview of African foods, and is worthy of study in classrooms across America.

Culinary Expeditions, A Celebration of Food and Culture is a wonderful cookbook with easy to follow recipes that are educational and useful for the home cook. It would make a terrific present for the host of a holiday meal over the next few weeks. Moreover, it’s an educational tool that should be used in schools everywhere. [Books can be ordered through the Women’s Committee Office ($25 plus shipping and handling): Ardeth Anderson at [email protected], or by phone at 215.898.9202. All proceeds benefit the Penn Museum.]

(Frank W. Barrie 11/19/14)