Fed-Up, a documentary film directed by Stephanie Soechtig, narrated by Katie Couric, and written by Mark Monroe and Ms. Soechtig (92 minutes) [Distributed by Radius-TWC, a boutique label from the Weinstein Company, 2014]

Fed-Up, a documentary film directed by Stephanie Soechtig, narrated by Katie Couric, and written by Mark Monroe and Ms. Soechtig (92 minutes) [Distributed by Radius-TWC, a boutique label from the Weinstein Company, 2014]

“Move more, eat less” has always seemed to provide an easily understood remedy for losing excess bodyweight. Burn more calories than you eat, and you’ll lose the pounds. With some determination and self-control, no need to carry around a layer of fat.

Fed-Up hammers home the point that what may seem so simple does not provide the answer to the extraordinary obesity epidemic that is raging in the U.S. and which, thanks to the popularity of the American fast food diet, has spread around the world. Following the personal stories of four obese young Americans (geographically diverse, living in Houston, Oklahoma City, a small town in South Carolina, and California) and their individual failures to improve their health and lose weight, Fed-Up makes plain that a sugar addiction (as powerful as an addiction to drugs like cocaine) has taken control of their eating habits. The obesity of these young Americans is not the result of their personal irresponsibility. Rather, this fearless documentary courageously places the blame on industrial food corporations that have added sugar (in its various forms) to their edible food products and beverages in order to increase sales and profit irregardless of health consequences.

This must-see film includes an array of interviews of physicians, nutritionists, scientists and other experts which adds special meaning to the telling of the personal struggles of the four young and obese Americans. No surprise to hear from the ever-thoughtful and articulate Michael Pollan and Marion Nestle, and kudos to the filmmakers for recognizing the credible voice of Dr. David A. Kessler and including his commentary. Dr. Kessler, the former Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), appointed in 1990 by the first President Bush and reappointed commissioner by President Bill Clinton, was one of the first to discuss the addictive nature of fat, sugar and salt. Unafraid to critique the food industry, whose mission is to get consumers to consume and which uses advertising to promote a culture of constant snacking, drinking and eating, Dr. Kessler early-on cited research in neuroscience and psychology, in his prescient The End of Overeating, Taking Control of the Insatiable American Appetite (Rodale, Distributed to the trade by Macmillan, New York, 2009), which established that foods high in fat, salt and sugar alter the brain’s chemistry, stimulating release of dopamine, which is associated with feelings of pleasure. (An adaptation by Dr. Kessler of The End of Overeating aimed at young adults titled Your Food is Fooling You: How Your Brain is Hijacked by Sugar, Fat, and Salt was recently published.)

Fed-Up has narrowed the focus to emphasize the addictive nature of sugar, since more than salt and fat, sugar consumption has spawned the obesity epidemic. Like Dr. Kessler, the filmmakers are unafraid to criticize the sophisticated marketing by the food industry which raises the hackles of the viewer since children are the frequent targets for the industry’s advertisements. It’s been estimated that children view nearly 4,000 food related ads each year, and 98% of these ads are for products high in fat, sugar and sodium. Of the 600,000 food items sold in America, 80% have added sugar, and the food industry is not just pushing hard to sell cookies and desserts. The cereal aisle in the modern supermarket is a danger zone. In 2012, every five days, Americans consumed an average of 765 grams of sugar which over one year equals 130 pounds of sugar. To burn off the calories in one 20 ounce bottle of soda, a 110 pound child would have to ride a bike for 75 minutes. No wonder that “move more, eat less” does not provide the simple answer.

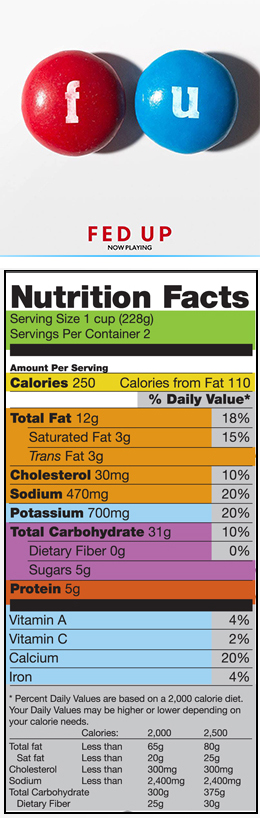

Fed-Up is a wake-up call to all Americans and effectively tells the maddening story how the sugar and processed food industry has resisted attempts to set reasonable guidelines for limiting the consumption of sugar as far back as the late 1970s. In particular, the film shows how industrial agriculture’s powerful lobby in Washington has succeeded in keeping the FDA’s standardized Nutrition Facts Label from requiring information on the “Daily Value” for the consumption of sugar despite recognition by other federal agencies that intake of added sugar should be limited.

The federal Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and of Health and Human Services (HHS) jointly issue and update every five years, “The Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” described as “the cornerstone of Federal nutrition policy and nutrition education activities.” The current guidelines note that Americans consume too many calories from solid fats, added sugar and refined grains, and that “healthy eating” limits intake of sodium, solid fats, added sugar and refined grains. The guidelines note that “healthy eating” emphasizes “nutrient-dense foods and beverages- vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products, seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, beans and peas, and nuts and seeds.” Nonetheless, the FDA, responsible for regulating the standardized Nutrition Facts Label required to appear on retail food products, has not provided a Daily Value for the consumption of sugar.

The Nutrition Facts Label separates “key nutrients” that “impact” health into two main groups, nutrients that “should be limited” and nutrients that consumers “should get enough of.” For Total Fat, Saturated Fat, Cholesterol and Sodium, all nutrients that should be limited, the Nutrition Facts Label provides the “Daily Value” for their consumption and also indicates the percentage daily value for these nutrients (based on a serving size of the particular food product). For example, for a 2,500 calories diet, total fat should be less than 80 grams; saturated fat, less than 25 grams; cholesterol less than 300 milligrams; and sodium less than 2,400 milligrams. Why has the FDA failed to require that the standardized Nutrition Facts label, show specific information on the “Daily Value” for the consumption of sugar and the percentage of such “Daily Value” which is reached by the consumption of a serving size of the particular retail food product? The answer is simple. The powerful lobby in Washington of the sugar and processed food industry has been successful in keeping specific information on the “Daily Value” for the consumption of sugar off the standardized Nutrition Facts Label.

As Michael Pollan has pointed out, sugar is often a “hidden” ingredient in processed food and his advice on the consumption of sugar and other sweeteners in his Food Rules, An Eater’s Manual (a reference book worth reviewing on a regular basis) includes all types of sugar in the same “avoidance” category. Pollan’s Rule 4, “Avoid food products that contain high-fructose corn syrup,” (as noted in the book review on this website) is “not because high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is any worse for you than sugar, but because it is, like many of the other unfamiliar ingredients in packaged foods, a reliable marker for a food product that has been highly processed . . . [and] it is being added to hundreds of foods that have not traditionally been sweetened.” Consequently, if HFCS is avoided, “you will cut down on your sugar intake.” His Rule 5, “Avoid foods that have some form of sugar (or sweetener) listed among the top three ingredients,” closely complements Rule 4. Pollan explains that “sugar is sugar,” and this avoidance of sugar guideline makes no exception for honey or molasses or maple syrup. The “so on” in the long list specified by Pollan of the “now some forty types of sugar used in processed food, including barley malt, beet sugar, brown rice syrup, cane juice, corn sweetener, dextrin, dextrose, fruicto-oligosaccharides, fruit juice concentrate, glucose, sucrose, invert sugar, polydextrose, sucrose, turbinado sugar, and so on” likely includes honey, molasses and maple syrup. Pollan even goes so far as “To repeat: Sugar is sugar. And organic sugar is sugar too.” Finally, he kiboshes any attempt to satisfy a sugar craving by using “non-caloric sweeteners such as aspartame or Splenda . . . (which) do not lead to weight loss, for reasons not yet well understood” though he suggests an explanation that rings true: “deceiving the brain with the reward of sweetness stimulates a craving for even more sweetness.”

The current draft guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) point out that sugars should make up less than 10% of total energy intake (calories consumed) per day, which is equivalent to less than 50 grams (approximately 12 teaspoons) of sugar per day for an adult of normal Body Mass Index. The FDA candidly admits in its explanation on “How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label” that “No daily reference value has been established for sugars because no recommendations have been made for the total amount to eat in a day.” Nonetheless, the Nutrition Facts Label does indicate the number of grams of sugar in a serving, and the adult consumer can use this label to keep track of sugar consumption. As noted above, every five days, Americans consume an average of 765 grams of sugar or over 150 grams per day, an amount three times greater than the WHO’s suggested daily limit of less that 50 grams per day of sugar.

Perhaps, Fed-Up hammers its points home somewhat repetitively, but the film’s message is so important that any repetition is easily swallowed by the viewer. Go see this film. And send a message to the FDA that the standardized Nutrition Facts Label should include specific information on the “Daily Value” for the consumption of sugar based on the WHO’s less than 50 grams of sugar per day.

(Frank W. Barrie, 6/11/14)