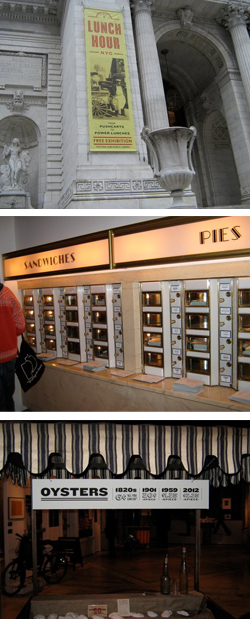

The New York Public Library at its main Fifth Avenue (at 42nd Street) branch, a Greek temple-like monumental building guarded by impressive stone lions, is currently hosting a thought provoking (and free) exhibit that is nothing less than an historical and cultural analysis of “the lunch hour” (until February 17, 2013): Lunch Hour, NYC (Open Mon, Thurs & Sat, 10:00AM-6:00PM; Tues- Weds, 10:00AM-7:30PM, Sun 1:00PM-5:00PM). Ada Louise Huxtable, the renown New York Times critic of architecture and urban planning, described New York City as “like no other city in time or place.” In her view (referenced in a New York Times obituary memorializing her recent death at 91), New York City inspires “awe” in the “presence of [its] massed, concentrated, steel, stone, power and life.” As the great urban metropolis of North America, with its thousands of restaurants and places to buy lunch, this exhibit’s claim that the urban phenomenon of lunch “acquired its modern identity on the streets of New York” rings true.

The New York Public Library at its main Fifth Avenue (at 42nd Street) branch, a Greek temple-like monumental building guarded by impressive stone lions, is currently hosting a thought provoking (and free) exhibit that is nothing less than an historical and cultural analysis of “the lunch hour” (until February 17, 2013): Lunch Hour, NYC (Open Mon, Thurs & Sat, 10:00AM-6:00PM; Tues- Weds, 10:00AM-7:30PM, Sun 1:00PM-5:00PM). Ada Louise Huxtable, the renown New York Times critic of architecture and urban planning, described New York City as “like no other city in time or place.” In her view (referenced in a New York Times obituary memorializing her recent death at 91), New York City inspires “awe” in the “presence of [its] massed, concentrated, steel, stone, power and life.” As the great urban metropolis of North America, with its thousands of restaurants and places to buy lunch, this exhibit’s claim that the urban phenomenon of lunch “acquired its modern identity on the streets of New York” rings true.

Colonial America mealtimes were based on rural English life, with a main meal known as “dinner” in the middle of the day. With the pressures of industrialization, especially in New York City, a growing center for trade, manufacturing and finance, the pattern of mealtime began to change. Dinner was pushed to the end of the day, and lunch settled into a scheduled place on the clock between noon and 2:00PM. The English word “lunch”, probably derived from Spanish “lonja” meaning “a thick piece” or “a chunk,” is first referenced in Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary as follows: “as much food as one’s hand can hold.” The American Noah Webster in his early 19th century dictionary defined lunch as “a portion of food taken at any time, except as a regular meal.” Not until the mid 19th century, with the urbanization and industrialization of American life, did lunch acquire the meaning of “a slight repast between breakfast and dinner.”

Curated by Rebecca Federman and Laura Shapiro, “Lunch Hour NYC” looks back on more than a century of New York lunches, and utilizes the extraordinary resources of the New York Public Library, which include one of the largest collections of menus in the world, now numbering 45,000. A menu dated January 9, 1900 for Childs’ Lunch Rooms, which operated several restaurants with “hygienic surroundings,” tiled floors, and employees in signature white uniforms, offered 2 scrambled eggs for 15 cents, a ham omelet for 20 cents, oatmeal and milk for 10 cents and the priciest lunch item, a sirloin steak for 30 cents. Dessert of a baked apple with cream cost 5 cents, stewed prunes, five cents.

A large section of the exhibit is dedicated to the recreation of a Horn and Hardart Automat, including “the famous machines” with their windowed compartments (behind which prepared foods sat plated), which opened by dropping nickel(s) in a slot. The “flagship” Horn and Hardart Automat restaurant opened in the middle of Times Square on July 2, 1912. Beginning in 1919, every Automat restaurant included a cafeteria, and the chain of Automat restaurants all over the city were popular not solely due to “the famous machines.” The exhibit suggests that the disappearance of the Horn and Hardart Automats, with the shut down of the last automat in 1991 after a decline that begun in the 1950s, resulted from two main factors: (1) the development of the suburbs and the loss of middle class city dwellers and (ii) increasing competition including the explosion of fast food restaurants in New York. The food served at the Automats was freshly prepared at a central commissary in Manhattan, and the Automats’ food and labor costs soared, and they couldn’t compete on price with the fast food chains. Famous Horn and Hardart recipes on postcards available at the exhibit, including one for Baked Beans, show that dishes were made with honest and recognizable ingredients. The Baked Beans recipe is worth trying. Ingredients consist of 1/2 lb. pea beans (smallest of the dried white beans, about the size of a pea, also known as a navy bean or a Great Northern white bean), 1/2 cup chopped onion, 2 strips raw bacon, diced, 1 tbsp. sugar, 1 tsp. salt, 1 and 1/2 tsp. dry mustard, 1/8 tsp. red pepper, 1/3 cup molasses, 1 tbsp. cider vinegar, 1/4 cup tomato juice, 1 cup water. Directions are straightforward: Soak the beans overnight (after rinsing thoroughly). Using the same water, boil, reduce heat, and simmer until tender, about 30 minutes or longer. Preheat the oven to 250 degrees. Add all other ingredients to beans. Pour into a baking pot or pan. Bake uncovered about 4 hours or longer. If necessary, add boiling water to prevent drying. Serves 4.”

One section of the exhibit of special interest is entitled “Charitable Meals” which cites the message of the urban reformer, Jacob Riis, that teaching the poor to cook and eat healthfully is an important key to progress rather than simply handing out food or cash. Reference is made to New York City’s school lunch program, begun in 1908, at an elementary school on West 44th Street with German and Irish students. (In the early 20th century, over 40% of the NYC population was foreign born, mostly from Europe.) Lunch consisted of thick slices of bread, warm soup, and a sweet potato for dessert. A 1902 photograph of the first Children’s Farm Garden in DeWitt Clinton Park on the Hudson River at 53rd Street between 11th and 12th Avenue brings to mind the work of today’s inspiring Edible Schoolyard program [www.edibleschoolyard.org]. The 1902 Children’s Farm Garden in NYC was the handiwork of Fannie Griscom Parsons, a leader of the early 20th century school gardening movement, which sought to provide neighborhood children with “the chance to grow their own vegetables and work hard in the fresh air.”

Thomas Jefferson in a 1787 letter to George Washington idealized small family farms: “The wealth acquired by speculation and plunder . . . fills society with the spirit of gambling. The moderate and sure income of husbandry begets permanent improvement, quiet life and orderly conduct, both public and private.” One wonders how Thomas Jefferson would respond to the section of this exhibit on the “Power Lunches” of the city’s wealthy power brokers. Somewhat surprising to this viewer was the reminder that, as recently as 1969, females were excluded from enjoying meals at some restaurants which served lunch to the powerful. In a photograph dated February 12, 1968, activist Betty Friedan is shown leading NOW members into the Oak Room, a restaurant in the famous Plaza Hotel, that barred women at lunchtime. Oak Room waiters refused to served the women led by Friedan. Later that year, the Plaza Hotel changed its policy.

On a lighter note, especially entertaining was the section of the exhibit on luncheonette slang and jargon. The expressive language lifts the spirits: axle grease (butter); cup of mud (coffee); one on a pillow (hamburger), put a stretch on it (sandwich to go). The exhibit also includes carefully selected art work: ranging from artful lithographs, Lunch (1936) and Waitress (1940) by WPA Federal Art Project artist, Jacob Kainen, to New Yorker magazine cover art related to lunch and food. The magazine cover art by Constantin Alajalov (September 5, 1942) showing a male/female lunchbreak divide at an aircraft factory and by Helen E. Hokinson (Febraury 26, 1938) depicting a chauffeur watching two upper class children buying a slice of cake from a windowed compartment at a Horn and Hardart Automat deserve special mention.

There may be no free lunch in NYC for the ordinary visitor, but this free exhibit is a wonderful way to spend a stimulating afternoon, and then, perhaps, might I suggest dining at one of the many restaurants in New York City that show a commitment to using local foods. It may be an urban metropolis, but New York City, has more listings for farm to table restaurants on our website than Portland, Oregon.

(Frank W. Barrie, 1/16/13)