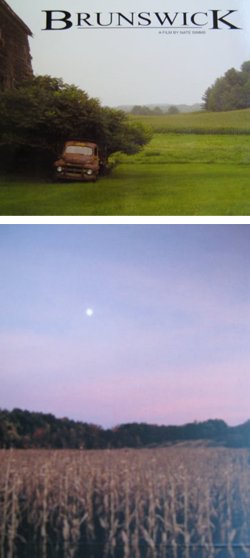

Brunswick, a documentary film directed by Nate Simms (56 minutes) [Country Boy Productions, 2011]

The town of Brunswick in upstate New York’s Rensselaer County is on the eastern edge of the rapidly suburbanizing Capital Region. The Capital Region’s three urban centers of Albany, Schenectady and Troy have all lost significant population in the past few decades, while the suburbs of Guilderland, Niskayuna, Clifton Park and Delmar have grown rapidly. The rural town of Brunswick, just east of Troy (and on the way to green Vermont), with its rolling hills and unspoiled country vistas, has become an attractive target for suburban developers.

Nate Simms’ moving portrait of an aging farmer, Sanford (“Sam”) Bonesteel and his loss of control over the future of his family farm, makes tangible the forces of suburban change and the vanishing of a rural way of life. The film’s story line is like a modern-day Anton Chekhov play, with unstoppable forces threatening the demise, in this case not of a cherry orchard, but a family farm.

In this well-made documentary film, the hard-worked hands of Sam Bonesteel, a 91 year old farmer, are first seen and his aggrieved voice is heard, before the weary face of this trusting man, who feels betrayed by the two sons of his closest friend, appears on the screen. Farmer Sam Bonesteel has sold his family farm of 210 acres for $268,000.00 to Phil and Ken Herrington, the sons of Sam’s brother-like friend and fellow farmer, George Herrington.

The story told by filmmaker Nate Simms is not a simple one: George Herrington’s third son, Harold Herrington, provides comfort and care to Sam Bonesteel, and is a credible voice in the documentary. He confirms in measured, unemotional tones that his brothers bought the old Brunswick farm from Sam with assurances that they would keep farming the land. However, an offer of $2,000,000.00 for the land by a developer is too good to be refused by the two Herrington brothers, Phil and Ken. The developer has plans to transform Sam’s farm into Highland Creek, an “active and fun, intergeneration community” with (i) 130 carriage houses for the empty nester purchaser, (ii) 39 traditional, single family homes, and (iii) 21 luxury manor homes, for the upscale buyer.

Brunswick provides a close-up look at the workings of a rural town board, on which Phil Herrington serves as Town Supervisor. Careful to recuse himself from voting on the development plans, Town Supervisor Herrington insists that all actions taken by the board were within the letter of the law. He dismisses challenges to development by a newly formed “citizen’s action group” called Brunswick Smart Growth as “political.” With another member of the town board the operator of a gravel and cement business whose business stands to prosper from suburban growth, the emotions of the opposition to the development plans run high that “conflicts of interest” of town board members are ripe.

The reflective and, at times, mournful musical soundtrack of Brunswick comes to joyful life when the film shifts to the workings of Homestead Farms, a community supported agriculture (CSA) farm, in the Cropseyville hamlet within the town of Brunswick, run by the Bulson Family. The family’s next generation young farmer, Sarah Bulson, rejects the notion that “farms have run their useful life” and asks “Where is food going to come from?” To be dependent on organic food from California makes little sense when a local farm can produce organic food nearby. Her words counterbalance the cynical testimony of one supporter of development at a town board meeting, who asserts that “agriculture is dead in New York State and not just in the town of Brunswick.” The camera’s loving shots of ripe red tomatoes and fresh organic produce grown by the Bulson’s Homestead Farm are worth thousands of words and provide a visual response to the cynical testimony that farmland in the town of Brunswick is “no longer viable” and “marginal.”

Brunswick is also a film about memories, and it skillfully weaves black and white still photographs, in a Ken Burns-like fashion, to tell the story of Sam and his wife Flora’s life on the family farm. Harold Herrington, the brother who is not part of the development project, recalls how Sam “came to work for my father when I was born” and was “always willing to help you,” and he continues to treat him as “still part of my family.” Sam Bonesteel died in the course of the making of Brunswick. Harold Herrington, who brings Sam into his own home for the last month of his life, restores faith in human kindness. In the words of CSA farmer Rich Bulson, the rewards in life are not always “financial.” The Bulson family could “make more money growing houses here,” but that’s “not what we’re about.” These hopeful signs make the words of Sam Bonesteel, “It broke my heart,” when he learned his farm would no longer remain farmland, a little less painful.

Following a recent showing of Brunswick at the Linda, WAMC Public Radio’s Performing Arts Studio in Albany, New York (as part of The Linda’s Food For Thought, Socially Relevant Cinema), a panel which included the filmmaker, Nate Simms, the musician and Brunswick soundtrack composer, Matthew Carefully, and a representative of American Farmland Trust, Laura Ten Eyck, responded to questions and comments from an appreciative audience. Ms. Ten Eyck noted that American Farmland Trust has recently published a guidebook for communities looking to support local farms called “Planning for Agriculture in New York: A Toolkit for Towns and Counties.” This publication highlights “how more than 80 towns and counties have taken action to keep farms viable and protect farmland” and includes information on zoning and land use planning, the purchase of development rights, and agricultural economic development. Although focused on New York State, this publication should be of interest to anyone interested in preserving farmland and small family farms and a free copy can be downloaded at www.farmland.org/newyork.

[Frank W. Barrie, 7/1/12]