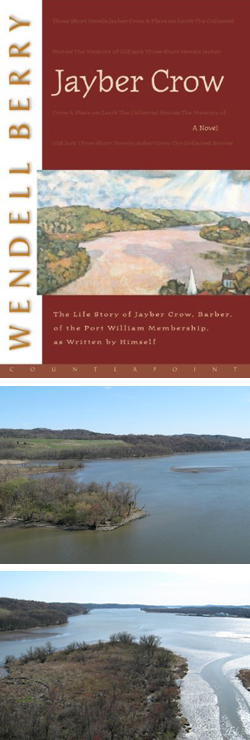

David Montgomery in his history of world agriculture, Dirt, the Erosion of Civilizations (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2007) details the disappearance of various societies as the consequence of the abuse of the fertility of a civilization’s soil and the resulting inability to provide an adequate food supply. Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow (Counterpoint, Berkeley, California, 2000), a powerful and loving portrait of a fictional barber of a small Kentucky river town, captures the collapse of a small town way of life, close to nature, and its replacement in post-World War II America, with a new society tied to the rush of the interstate and a system of industrial agriculture heedless of the environment and the past.

The novel’s narrator, Jayber (born Jonah) Crow, is a keen observer of the effect of time passing on the life of his small Kentucky river town in his remarkable tale of love. The full title of Mr. Berry’s novel, Jayber Crow, The Life Story of Jayber Crow, Barber, of the Port William Membership, as Written by Himself, reflects the very personal nature of the tale as the reader follows the narrator from his birth in 1914 to 1986, when he looks back at his life and tells his story. After a page for acknowledgements, a Notice is provided for the reader “BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR.” Whether “author” refers to Mr. Berry or to Mr. Crow is unclear. Nonetheless, any book reviewer is warned, in a Mark Twainish fashion:

“Person attempting to find a ‘text’ in this book will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a ‘subtext’ in it will be banished; persons attempting to explain, interpret, explicate, analyze, deconstruct, or otherwise ‘understand’ it will be exiled to a desert island in the company only of other explainers.”

With my apologies to the two, Mr. Berry and his fictional voice, this powerful novel deserves a wide readership, and has a very special appeal for readers, who are searching for a new way to feed themselves, which protects the environment and builds community. The modern movement of CSA farms, farmers markets, and community gardens, which this website promotes, is a sign that hope is not lost, and nature and community may be respected. Jayber Crow, which in good part centers on the sad collapse of a family farm, can serve as a reminder of what has been lost and needs to be remembered.

Athey and Della Keith’s 500 acre Kentucky farm has a richness “both in evidence and in reserve” of “bottomless fecundity,” which is wasted away by their daughter’s husband, Troy Chatham, in the course of a transforming American industrial agriculture, with its “dependence not on land and creatures but on machines and fuel and chemicals of all sorts, bought things, and on the sellers of bought things -which made it finally a dependence on credit (p.183).” With 12 working mules, Athey Keith “raised tobacco and corn, followed by wheat or barley, and then by clover and grass. He had cattle and sheep and hogs (p. 178).” Jayber Crow lovingly recalls Athey Keith’s way of farming:

“What I do know is that he used his land conservatively. . . In any year, by far the greater part of his land would be under grass . . . He was always studying his fields, thinking of ways to protect them . . . he was improving his land; he was going to leave it better than he had found it. . . ‘Wherever I look,’ he said, ‘I want to see more than I need, and have more than I use.’ And this is a principle very different from what would be the principle of his son-in-law, often voiced in his heyday: ‘Never let a quarter’s worth of equity stand idle. Use it or borrow against it.’ (pp 178-179).”

Athey and Della Keith’s “place” included “seventy-five or eighty acres of very good timber” known as the “Nest Egg,” which takes on special importance, in the manner of the great Anton Chehkov and his Cherry Orchard. “The finest stand of trees in our part of the country. . . [Athey] protected it from timber buyers . . . As long as he could make a living farming, that patch of timber would always be worth more to him than to them. . . Whose nest egg it was he never said (pp.179-180).”

By the end of the barber’s story, Troy Chatham has turned the Keith farm into a kind of wasteland and the Nest Egg into dollars. Troy Chatham and Athey Keith were “different, almost opposite, kinds of men.” Troy “asked of the land . . . all that it had” and was unable to see and appreciate the old farm’s “patterns and cycles of work:”

“[I]ts annual plowing moving from field to field; its animals arriving by birth or purchase, feeding and growing, thriving and departing. Its patterns and cycles were virtually the farm’s own understanding of what it was doing, of what it could do without diminishment . . . The farm, so to speak, desired all of its lives to flourish (p. 182).”

This old “order” of farm life stood in the way of Troy’s vision of using the farm “to serve and enlarge him.”

Jayber Crow’s description of Troy’s transformation of the Keith family farm is grave:

“[T]he still unharvested corn crop that I was walking through was poor for the year, and so overgrown with Johnsongrass that you could hardly see the rows . . . I could see that the soil was pale and hard, lifeless, and in places deeply gullied. . . Troy had bulldozed every tree . . . from every foot of ground where you could drive a tractor. The fences were gone from the whole place. Troy was a hog farmer now. Hogs were the only livestock on the farm, and they were all inside pens in the large hog barn that I could smell a long time before I could see it. . . [T]he other farm buildings looked abandoned- paintless and useless, going down. . . Behind the barn lots was what I had heard Troy . . . call his ‘parts department.’ This was a patch of two or three acres completely covered with old or broken or worn-out machines. . . Every scrap of land that a tractor could stand on had been plowed and cropped in corn or soybeans or tobacco. And yet, in spite of this complete and relentless putting to use, the whole place . . . did not look like a place where anybody had ever wanted to be. It and the farming on it looked like an afterthought. It looked like what Troy had thought about last, after thinking about himself, his status, his machinery, and his debts (p. 340).”

But Jayber Crow is much more than the story of the ruin of a family farm, resulting from the ill-conceived dreams of a wannabe agri-businessman. At its heart is a transcendent love story, where a life affirming “Yes” spoken by the narrator’s soul mate on her death bed, gives hope for the human ability to love, rather than hate. Wendell Berry, a proud Kentuckian, has made a small river town the center of a tale of transforming love. Jayber Crow is a book to read and savor, especially now, in light of the great honor recently bestowed on Mr. Berry [knowwhereyourfoodcomesfrom.com/2012/02/09/wendell-berry-honored-as-2012-jefferson-lecturer-in-the-humanities/].

[www.wendellberrybooks.com/]

(FW Barrie, 4/2/12)