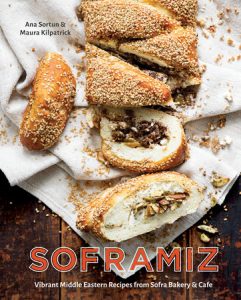

A Cookbook That Celebrates Flavorful & Vibrant Middle Eastern Recipes

Chef Ana Sortun graduated from La Varenne in Paris, but her interest in Middle Eastern food has taken her beyond that classical French foundation. She opened her first restaurant, Oleana, in Cambridge, Mass., in 2001; she now also owns Sarma, a Turkish-style tavern, and Sofra Bakery & Café, all in the same general area. And it doesn’t hurt that her husband, Chris Kurth, owns and operates nearby Siena Farms.

Chef Ana Sortun graduated from La Varenne in Paris, but her interest in Middle Eastern food has taken her beyond that classical French foundation. She opened her first restaurant, Oleana, in Cambridge, Mass., in 2001; she now also owns Sarma, a Turkish-style tavern, and Sofra Bakery & Café, all in the same general area. And it doesn’t hurt that her husband, Chris Kurth, owns and operates nearby Siena Farms.

She won the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Northeast” designation in 2005, even as she was working on her first cookbook, Spice: Flavors of the Eastern Mediterranean. Her latest book is Soframiz: Vibrant Middle Eastern Recipes from Sofra Bakery & Café (Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, California, 2016), co-written with Maura Kilpatrick, a longtime cooking partner who specializes in pastry.

We learn from the start that sofra encompasses everything you prepare for the table: food, place settings, glassware, décor, linens. (The literal translation from Turkish is table, allying it with an old-fashioned English sense of the term.) Soframiz means our sofra, which is as welcoming a title as you could wish.

It’s a handsome book with a hundred recipes, but be warned that these recipes aren’t always easy. Nor should they be. We confuse cooking with convenience, and we lack the tradition of handing down recipes and techniques across generations. Which means that scratch cooking usually means learning it from scratch. Fortunately, the procedures herein are laid out in careful detail, with choice photographs by Kristin Teig to illustrate the more complicated steps.

Take the recipe for Cheese Borek with Nigella Seeds. It’s a seemingly simple pastry, but wait. It’s made with several layers of yufka dough, which is almost as thin as phyllo pastry. Sortun confesses to using store-bought yufka because she doesn’t find that the yufka recipes in the book can be rolled thin enough – but there are two such recipes to choose from. She recommends the one that’s enriched with milk and egg.

I don’t find this to be complicated: It’s thorough. It invites experimentation, which is how you learn the techniques of cooking.

Once you have the dough ready, it’s cut to fit a baking dish and layered therein, each layer brushed with a yogurt-and-egg mixture. Eight layers in all, with a sprinkling of grated mozzarella in the middle. The dish is topped with nigella seeds before going into the oven.

The Essential Ingredients section at the back of the book tells us that they look a lot like black sesame seeds, but they are not related. But they have a unique, peppery flavor that makes them worth having on hand.

I suggest that you read the book’s chatty introduction first, then skip to Essential Ingredients and take in those 15 pages. (The essay on olive oil alone is worth it.) Then make your way through the recipe sections. There are eight: Breakfast, Meze, Flatbreads, Savory Pies, Cookies and Confections, Specialty Pastries, Beverages, and Pantry. As the intro to the last-named section puts it, Homemade is happiness, and the Middle Eastern pantry is stocked with sauces, preserves, and condiments to capture the bounty of a season and pack away vivid flavors to have on hand.

The recipes feature a generous array of baked goods, often built around meats – particularly ground or sausage – and vegetables. The Meze section is described as being tapas-like, to make the experience at the table last as long as possible. It’s long on salads and other vegetable-based items. One of my favorite crops from my husband’s garden are his fall carrots, writes Sortun, explaining that the sugars are more concentrated in them at that time of year. And the recipe for Persian-Style Carrots and Black-Eyed Peas is built around them, a fairly simple sauté that only requires some care in the black-eyed peas prep. It also features a seasoning dubbed Persian Spice, also known as advieh, which enhances both savory and sweet dishes and features nutmeg, coriander, cinnamon, black pepper – and dried rose petals.

(You’ll find recipes for that and many other evocative blends in the Pantry section, which covers not only spices but also pickled turnips, pumpkin or rose petal jam, and one of my all-time favorites, toum, a garlic paste that Sortun has modified slightly by sweetening it with milk.)

There’s potential for fresh ingredients throughout: Dragon Bean Plaki uses fresh wax beans; Barley and Chickpea salad depends on locally harvest barley (along with parsley, mint, and dill, a threesome that appears frequently); fresh tomatoes are featured in a bulgur-based salad and many other recipes.

And then there’s hummus. Sortun hopes the recipes herein inspire you to consider hummus as a blank canvas for many different toppings and prove that hummus is not just a dip for vegetables. You’ll be introduced to Warm Buttered Hummus, Spicy Lamb, and Pine Nuts; Walnut Hummus, Pomegranate, and Cilantro; and Buttermilk Hummus with Celery Root and Pumpkin Seeds, but these also point the way to your own hummus recipes.

You’ll meet more meat in the Flatbreads section, where lamb and chicken shawarma are described – or a Red Lentil Durum with Pickled Peppers for a veggie version. As next year’s garden begins to produce, I have my eye on the Summer Vegetable Lamejum, kind of cross between a soft taco and a pizza, with a topping of roasted eggplant, onions, and tomato flavored with haloumi cheese (a sheep’s-milk variety) and pomegranate molasses.

This spirit carries into the Savory Pies, where the familiar Spanakopita is turned into a spiral, where ground lamb is mixed with tomato paste, cumin, and orange zest before being baked inside grape leaves; where manouri cheese (made from the cream-enhanced whey of the feta-making process) is mixed with honey and walnuts before going into a tart shell.

The danger in this book is that it devotes two chapters to sweets. First the cookies. Two difficulties inform the Syrian Shortbreads: first, the prep time. You have to clarify a cup of butter and then refrigerate it for an endless couple of hours. The first mixing stage requires another two hours in the fridge. Then you mix it some more and leave it in the icebox overnight! As if that doesn’t tax the patience enough, there’s another hour and a half of refrigeration needed as you form the cookies, after all of which the half-hour in the oven seems like nothing. The second difficulty is keeping any of these cookies in the house. It wouldn’t be any safer with the Marzipan Cookies with Figs and Walnuts, I suspect, although I haven’t had the chance to make them yet. I’ll be making the Sesame Cashew Bars first.

The fusion aspect of these recipes is exemplified by the Brown Butter Pecan Pie with Espresso Dates. As Kilpatrick explains, they took an American classic and eased it into the Sofra repertoire by having some fun with ingredients, namely dates. And not just that – the dates are soaked in espresso before they line the bottom of the crust. A Greek custard called bougasta becomes Milk Pie in Kilpatrick’s hands, thickened with semolina flour, and with phyllo top and bottom. You can make baklava on your own; here, you’re offered recipes for a Milky Walnut-Fig Baklava or a Chocolate Hazelnut version.

I’ve whisked you towards the back of the book because I know you’re going to be hung up at the first recipe section – Breakfast. One of the best spreads in all of Istanbul is a breakfast where the olives, tahini, stuffed flatbreads, egg dishes, vegetables, and cheeses cover the entire table. You can go simple with Shakshuka – baked eggs with spicy tomato sauce. Or you can soft-boil those eggs, roll them in flour and egg wash, and wrap them in kataifi (shredded phyllo), then fry them alongside cubes of feta.

Kohlrabi is picked spring and fall at Siena Farms, and inspired one of the favorite dishes at Sortun’s restaurants: Kohlrabi Pancakes with Bacon and Haloumi Cheese. Don’t even get close to thinking in terms of diner-fare flapjacks: these are savory wonders. There’s an assortment of brioche variants here, all made with a tahini dough. There’s even a recipe for Olive Oil Granola with dates and almonds.

As noted earlier, some of the procedures are complicated but none looks especially difficult, especially considering the ease of the prose that describes them. But providing ingredient amounts by weight (as well as by volume) would have been helpful.

Soframiz: Vibrant Middle Eastern Recipes from Sofra Bakery & Café is valuable both as a recipe collection and a kitchen inspiration, opening flavor vistas and describing fresh approaches to cooking techniques. As the book’s title suggests, dining is about hospitality, and it’s celebrated nicely here.

(B.A. Nilsson, 12/20/19)

Blending Spices to Share This Holiday Season: Homemade Herbes de Provence

The Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY, with its nearly 1000 bins of bulk food, also has an area in the store for herbs and spices where customers can buy as much, or as little, as desired

The Honest Weight offers Frontier Co-op’s Herbes de Provence as a ready-made blend of herbs but the ingredients are conventional and not organic

Nearly half of the herbs and spices sold at the Honest Weight are organic and the price differential is not that great given that herbs and spices do not “weigh” heavily and an ounce or two often fills up a small jar (and to avoid any possible residues from pesticides/fertilizers when conventionally grown is priceless)

A spice bag filled with 3 tablespoons of a homemade and organic blend of Herbes de Provence makes for a sure to be appreciated holiday stocking stuffer for a homecook (and a jar filled with the leftover for longer-term storage for the gift-giver!)

In the 1970s, commercial blends of dried herbs, typical of the Provence region of southeast France, became popular and successfully marketed as Herbes de Provence. According to the Wikipedia article on this mixture of spices, Provençal cuisine has traditionally used many herbs which were often characterized collectively as herbes de Provence, but not in specific combinations, and not sold as a mixture.

The commercial blends commonly include rosemary, thyme, oregano, savory and marjoram. The entry in Wikipedia elaborates that homogenized mixtures were formulated by spice wholesalers and for the North American market, lavender leaves were also typically included due to American association of Provence with fields of lavender.

A recent article in Heirloom Gardener (Fall 2018), Homemade Spice Blends by Haley Casey, caught this home cook’s eye. With a turkey to roast for Christmas, a recipe for homemade Herbes de Provence seemed a handy way to make a customary main course, flavorful and special for the holiday celebration. And blending organic herbs (including some grown in a backyard garden as well as some from this past season’s CSA farm share) into homemade Herbes de Province would also make for appreciated seasonal gifts.

In addition to the six herbs commonly included in the commercial blends as noted above, the recipe in Heirloom Gardener includes basil, mint and fennel seeds. With basil home grown in the backyard garden and also part of a CSA farm share (and dried for use as a seasoning throughout the year), and peppermint also homegrown and dried for tea and use as a seasoning, little question that these two flavorful herbs would be added to my homemade blend.

Fennel seeds were not a familiar seasoning, but on a visit to the herbs and spices section of the bulk foods department of my hometown Honest Weight Food Co-op, it took only a sniff of the container of fennel seeds and its fragrant licorice-like aroma to decide to include the spice in the home crafted mixture.

Heirloom Gardener’s Haley Casey notes in her article that the suggested blend of herbs is often adjusted based on household preference, so the precision of the measurements or the addition of some tarragon or sage is up to you.

Classic Herbes de Provence (adapted from a recipe by Dana Goldstein and included in the Fall 2018 issue of Heirloom Gardener)

3 tablespoons thyme

2 tablespoons basil

2 tablespoons savory

2 tablespoons oregano

2 tablespoons marjoram

2 tablespoons rosemary

1 tablespoon fennel seeds

1 tablespoon lavender

1 tablespoon mint

Thoroughly combine ingredients.

Yields about 1 cup.

The two tablespoons of basil I used in the recipe were a blend of basil grown organically in my backyard and from my CSA farm share from Roxbury Farm in Kinderhook (Columbia County), NY which I dried for use throughout the year. The peppermint was also home grown and similarly dried for use as tea and as an herb. (Last year, we shared our method of drying herbs by using an oven at 170 degrees for a couple of hours.) Other organic herbs were purchased at the Honest Weight Food Co-op, with its remarkable 1000 bins of bulk foods and a large herbs and spices section. Although the co-op offers Herbes de Provence as a blend of herbs ($24.40/lb), the herbs are conventionally grown and with more thyme and rosemary than the blend of herbs in this recipe. I was pleased to be able to purchase the individual organic herbs at the co-op to make my own blend.

I filled four spice bags, with 3 tablespoons of homemade Herbes de Province, for holiday gifts. The leftover I stored in a small glass jar.

Regency Naturals Spice Bags, made of 100% cotton, available at The Cook’s Resource, Different Drummer’s Kitchen Co. in my hometown of Albany, NY were handy to use.

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/14/18)

Marketing Campaigns By Coca Cola & Jamba Juice Challenged In Court By Center For Science In The Public Interest

Dr. Peter G. Lurie, the president of the Center For Science In The Public Interest (CSPI), summarized (in a year-end appeal for member support), the three immutable principles guiding the organization’s work: (i) People deserve honest, reliable nutritional information about the food they eat; (2) Our government must protect its citizens from dishonest marketing practices (emphasis added), dangerous food additives, and invisible, sometimes deadly pathogens; and (iii) Decisions about what goes into our food – and more importantly what is kept out – must be based on the best, most reliable science, not on maximizing the profits of big food corporations.

Dr. Peter G. Lurie, the president of the Center For Science In The Public Interest (CSPI), summarized (in a year-end appeal for member support), the three immutable principles guiding the organization’s work: (i) People deserve honest, reliable nutritional information about the food they eat; (2) Our government must protect its citizens from dishonest marketing practices (emphasis added), dangerous food additives, and invisible, sometimes deadly pathogens; and (iii) Decisions about what goes into our food – and more importantly what is kept out – must be based on the best, most reliable science, not on maximizing the profits of big food corporations.

When the government fails to protect its citizens from dishonest marketing practices, the CSPI has pioneered the use of civil litigation to stop deceptive, false and misleading advertising. Nonetheless, Dr. Lurie observes that sometimes “just a phone call or letter from our lawyers can effect marketing changes.”

But when a phone call or letter is insufficient, the organization uses the power of litigation to win more honest marketing. Current litigation maintained for that purpose includes two recent lawsuits.

The CSPI has filed a lawsuit on behalf of Pastor William H. Lamar IV, Pastor Delman L. Coates, and the nonprofit Praxis Project against The Coca-Cola Company and its trade association, the American Beverage Association. They allege that the defendants are engaged in an unlawful campaign of deception to mislead and confuse the public about the health harms related to sugar drinks.

According to the plaintiffs, credible science linking the consumption of sugar drinks to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease is undermined by the defendants’ marketing and advertising campaigns which promote lack of exercise as the primary driver of these diseases. Plaintiffs also complain that the defendants’ marketing and advertising leads consumers to believe that all calories are the same, when science indicates that sugar drinks play a distinct role in obesity and related epidemics, since such drinks have no nutritional value beyond calories.

The CSPI has also maintained a class action lawsuit against Texas-based Jamba, Inc. and its California subsidiary Jamba Juice Co. This lawsuit alleges that the chain is misleading customers about the ingredients and nutritional value of its smoothies.

While Jamba’s marketing states that its smoothies are healthful and made from whole fruits and vegetables, the complaint states that the drinks are in fact high in calories and sugar and made with fruit juices from concentrate. In addition, it’s alleged that many of the smoothies are made with sherbet or frozen yogurt that contains substantial levels of sugar and corn syrup with a single drink having up to 30 teaspoons of total sugars- bearing little resemblance to the healthful snack advertised. The marketing by the defendants of its smoothies as containing no raw sugar or high-fructose corn syrup is forcefully challenged.

A few years ago in reviewing Fed-Up, a documentary film narrated by Katie Couric, we noted that the maxim, move more, eat less, is not the easy remedy for the extraordinary obesity epidemic that is raging in the United States and which has spread world-wide. Instead, as Fed-Up makes plain in following the personal stories of four obese young Americans, a sugar addiction has taken control of their eating habits.

Hats off to the Center For Science In The Public Interest for challenging food corporations that deceptively market food products and beverages containing added sugar at the root of the obesity epidemic given its addictive nature.

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/8/18)

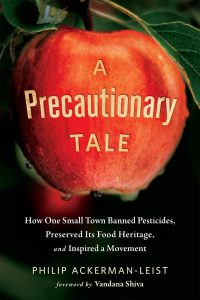

How to Fight the Pesticide Giants Revealed In An Inspirational Story of Local Activism

Preaching precaution (caution employed beforehand or prudent foresight) isn’t the same as practicing it. And the ounce of prevention principle, seemingly instilled in us at birth, has long gone out the window where pesticide use is concerned. Touted as the farmer’s salvation before risks were revealed, pesticides spawned a massive and profitable industry that flourishes, like any drug dealer, by keeping its users hooked.

Preaching precaution (caution employed beforehand or prudent foresight) isn’t the same as practicing it. And the ounce of prevention principle, seemingly instilled in us at birth, has long gone out the window where pesticide use is concerned. Touted as the farmer’s salvation before risks were revealed, pesticides spawned a massive and profitable industry that flourishes, like any drug dealer, by keeping its users hooked.

As a political device, the Precautionary Principle – so named in the late 1980s – found a more secure footing in the European Union than it has in the United States or Canada:

In Europe the precautionary principle serves as a fundamental basis for generating sound public policy; public health and safety generally trumps potential threats to it. In the United States, however, dangers have to be established through what is generally termed risk analysis, meaning that ‘acceptable levels of risk’ are established. … Precaution tends to be more of an afterthought than a guiding principle in the United States, and more of a guiding light in Europe.

The quote comes from Philip Ackerman-Leist’s A Precautionary Tale, How One Small Town Banned Pesticides, Preserved Its Food Heritage and Inspired a Movement (Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, 2017) which tells the story of the small European village that took on and bested a corporate assault that would have spelled doom for family-scale subsistence farmers – which was pretty much everybody not growing pesticide-anointed apples.

Mals is a town of 5300 inhabitants in the South Tyrol, technically in Italy’s Trentino-Alto Adige region, but with a history that aligns it with the bordering countries of Austria and Switzerland. Owing to its ruggedly mountainous terrain, this Alpine region tends to pursue its own distinct identity, so when Big Apple began to move in and take over more and more of the area’s scant farmland, there was a sense of live and let live among most of the neighbors – but a few of them initially saw reason for concern.

Günther Wallnöfer, for example. He’s the first of several residents we meet during the course of this book, and he may have been the first to feel the ill effects of apple-spraying. Supporting a family on his 47-acre dairy farm would be easier if his operation were certified organic, he decided, what with the revenue increase such certification provides. He made the change in 2001; a decade later, his crop samples, which required annual testing to maintain his certification, sported pesticide residue.

Wallnöfer buttonholed Ulrich Veith, the young, newly elected mayor of Mals, to complain of the problem. Veith was the right person to consult, because they shared one thing in common: a deep passion for what they both dubbed a sustainable future for Mals.

This kicks off a saga that introduces the people who would launch the anti-pesticide movement, alongside historical portraits of the region. From medieval times through World War Two, it’s been an area prone to siege. Its mountains and valleys have offered natural defenses, while aiding its climate in a limited amount of specialized growing. But that climate is warming, allowing a longer growing season, bringing with it this brand-new siege.

Ackerman-Leist has his own connection with area, one that goes back to 1983, when he spent a semester abroad at the Brunnenburg Castle and Agricultural Museum. This was housed in a 13th-century structure in the South Tyrol, a few miles west of Mals. Ackerman-Leist returned to the castle a few years later to work at its orchards and vineyards. While he loved the agricultural diversification of the area, by 1994 he’d had enough of spraying pesticides on crops. Back in the U.S., he developed the sustainable agriculture curriculum at Vermont’s Green Mountain College, where he continues to farm and teach. He also takes his students to Brunnenburg to study its farming practices and museum. It was while preparing for such a tour in 2014 that he learned of the upcoming Mals referendum, and he was floored: It was the first time the citizens of any town in the world had ever voted on whether to eliminate the use of all pesticides in their community.

The history of apples in the valley is relatively recent; by 1945, the leaders of fruit cooperatives in the area formed its own organization to help the area growers produce their annual one million tons of apples, from a province about half the size of Connecticut with an average family orchard size of 6 to 7.5 acres. But they proved to be part of the problem. A well-established farming practice (in this case spraying pesticides to ensure a bumper crop of marketable apples) produces a strong sense of entrenchment.

The author’s journey to learn the history of this revolution included visits to Urban and Annemarie Gluderer, who switched from apple growing to an organic herb farm in the valley. They had to take action when the apple-growers on three sides of their property persisted in reckless spraying, and even after spending $200,000 for a fully-enclosed greenhouse setup to protect them from the drift, their harvests were showing contamination.

We also meet Edith and Robert Bernhard, who created a valuable seedbank and sought to protect that legacy; veterinarian Peter Gasser, a longtime member of a local environmental protection group who recognized the imminent pesticide peril; Franz and Pius Schuster, the fourth generation to operate the Bäkerei Schuster in the village of Laatsch, who felt the effects of climate change and pesticides on the local grain; and Johannes Unterpertinger, the pharmacist who became a spokesman for the effort, but whose outspoken manner brought personal threats and property vandalism.

Early in 2013, over 70 Mals residents formed the Advocacy Committee for a Pesticide-Free Mals, but the effort truly picked up steam when Martina Hellrigl and Beatrice Raas enlisted a group of area women to make their feelings known through a display that appeared overnight of banners hung throughout Mals. (If your German is good, you can read about their ongoing efforts at hollawint.com. Hollawint is an exclamation of warning in Tyrollean dialect.)

While the satisfying conclusion is (more or less) foregone, nonetheless efforts to fight the measure prohibiting pesticide usage continue. Most important, the trip we take through this book to get there is a fascinating study of how local activism, from people who never would have imagined themselves to be activists, can make a significant and life-bettering difference. And it finishes with advice on how to do just that in your own locality.

Plus, A Precautionary Tale is a discursive book, but in a good way, filled with engaging bits of history that help with understanding the subject region – however tangential those connections may be. Thus we get a chapter on Ötzi, the frozen, remarkably intact corpse discovered high in the Ötzal Alps, a corpse that had lain there for several thousand years. His digestive-tract contents provided an unprecedented look at the diet and travels of early man; the tools he carried offered new insight into the development of such. [Editor’s Note (FWB): Ötzi is credited with the first meal known to have been eaten by a human (a 5,000 year old meal) which was recreated and on display at the American Museum of Natural History’s exhibit, Our Global Kitchen, Food, Nature, Culture.]

Ackerman-Leist’s writing style has the casual, informative feel of good journalism, although his sometimes too-forced puns and wisecracks can prove distracting. But it’s more than a precautionary take: it’s an inspiring one. And it’s a story that’s not finished yet in Mals even as it begins to play out in other parts of the world. It should prove to be a valuable handbook as we all fight the necessary fight against the pesticide Goliaths.

(B.A. Nilsson, 12/3/18)

The Carrot Project Grows the Local Farm Economy

The Carrot Project assists small New England and Hudson Valley farms and local food businesses in becoming economically sustainable

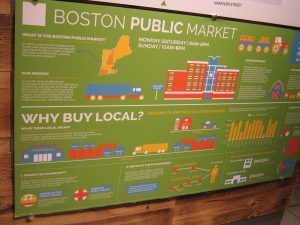

The Carrot Project’s fundraiser was held at The Kitchen of the Boston Public Market, an indoor, year-round market offering fresh, locally sourced food from nearly 40 New England farmers, fishers & food entrepreneurs

Siena Farms which supplies Sofra Bakery, recently reviewed here, coincidentally operates a farm stand at The Boston Public Market

The Carrot Project views as clients the farmers and businesses it works with directly. For over ten years, it has helped to build the financial management skills of its clients, and it takes pride in its 2017 Outcomes: 72 clients (whose service ended in the year) averaged an increase in net income of $28,500, 1767 farmland acres in production, and 47.5 jobs supported. And in 2017, it oversaw loans totaling $467,000 to current borrowers.

To meet its mission of increasing the number of profitable, viable farm and food businesses, The Carrot Project collaborates with various lending institutions. Earlier this month, its Ready to Grow fundraiser at the Boston Public Market was sponsored by Farm Credit East, SlowMoney Boston, Fresh Pond Capital, Eastern Bank, Honeybee Capital Foundation, and Trillium Asset Management.

The fundraiser, A Meet + Eat with Local Farmers, spotlighted two small farms, Three Maples Market Garden in West Stockbridge (Berkshire County, MA) and Ironwood Farm in Ghent (Columbia County, NY).

Three Maples Market Garden was started by Cian and Amanda Dalzell as a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm share, noting that they loved knowing the families who were eating our produce. They grow an impressive array of crops: squash, kale, carrots, cucumbers, peppers, eggplant, cabbage, tomatoes, turnip, rhubarb, zucchini, daikon, scallions, potatoes and radishes, as well as herbs, basil, sorrel, parsley, cilantro, dill, celery herb, tarragon, rosemary, and thyme. Cian Dalzell took a Making It Happen farm financial management course with The Carrot Project and has also trained to work as an instructor and business advisor to pay it forward.

Ironwood Farm is an impressive organic farm, certified organic by the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) of New York, on ten acres of leased land. The farm sells its produce at farmers markets, wholesale to restaurants, shops and resellers in New York’s Hudson Valley, and it also offers CSA farm shares. This certified organic farm is the collaboration of three women working together for seven years who hoped to achieve more together than apart and now make an income for each of their three households.

In addition, The Carrot Project at its recent fundraiser honored Scott Budde, who worked with the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MORGA) and Maine Farmland Trust to found the first credit union (Maine Harvest) focused on improving a local food system by lending to small farms and food producers, opening January 2019, with a capitalization of $2.4 million.

Investors and lenders helping to sustain the good food movement, rooted in small farms and local food producers, deserve gratitude for helping to counteract corporate gigantism, as evidenced by recent data released by the Open Markets Institute, showing increasing market share of the largest companies in many American industries, including the production of various agricultural products. For example, four giant enterprises, JBS SA, Tyson, Cargill and Smithfield have a market share of 53% (a 250% increase from their 21% market share back in 2002) of the Meat Processing Industry’s revenue (noted to be $123.2 billion in the data released by the Open Markets Institute).

Investors and lenders mindful of the ideals that monopolies undermine- like market competition, economic dynamic and individual freedom (in the words of David Leonhard in his op-ed, The Monopolization of America, NY Times, 11/26/18) deserve recognition.

Kudos for The Carrot Project in building the financial management skills of small farms and agricultural businesses and bringing together lenders and investors with well-managed small farms and local food businesses. The Project’s special recognition of two successful small farms and a caring investor/lender at its fundraiser earlier this month was a very special occasion worth celebrating.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/27/18)