Archive for November 2016

Cranberry Pecan Muffins: Thanksgiving Breakfast Treat

Organic Cape Cod cranberries, star ingredient for Thanksgiving breakfast treat

Bennington Pottery markings underneath stoneware muffin pan

I was recently greeting by the pleasing sight of organic Cape Cod cranberries for sale at the Honest Weight Food Co-op in my hometown of Albany, New York. Last autumn, the co-op’s Produce Department wasn’t able to get a supply of this seasonal fruit from Cape Cod (a popular vacation destination for people who live in the Capital Region of upstate New York), and I settled for organic cranberries from Michigan.

But this year I was able to stock up on Cape Cod cranberries. Now when I add a handful of cranberries to my morning oatmeal as it cooks on the stovetop, I can let my mind wander to the Cape. Breakfast tastes even a little bit better in that state of mind.

With a nice supply of Jonathan’s New England Heritage Organic Cranberries from Cape Cod on hand, I decided to indulge by baking up some cranberry pecan muffins to celebrate the Thanksgiving holiday, the “greatest of all national food fests” in the words of Judith Barter the curator of the terrific art exhibit, Art and Appetite (reviewed a couple of years ago on this website). [At the entrance to this exhibit, on display was Norman Rockwell’s Freedom From Want (1942), on loan from the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, painted at the height of World War II. As pointed out by curator Barter, Rockwell “made the turkey and its holiday a symbol of American values, freedom, and peace.”]

In the mood to celebrate the holiday, it was an easy decision to bake up some cranberry pecan muffins as a special treat for Thanksgiving morning using the Cape Cod cranberries. My starting point was the ever-handy cookbook, Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker, and Ethan Becker (New York, NY: Scribner, 1997). I love the encouragement given in the cookbook: “Remember that muffins invite substitutions and inventive flavoring, and that any coffeecake, quick loaf, or corn bread batter can be made into muffins as well” (p. 782).

The Joy of Cooking’s Basic Muffins With Milk or Cream (p. 783) was the foundation for my “inventiveness” rooted in my desire to use organic and local foods, and of course, Cape Cod cranberries. The following recipe substitutes kefir (Redwood Hill Farm Cultured Goat Milk Kefir) for milk, Sweet Brook Farm maple syrup for sugar, sunflower seed oil (Napa Valley Naturals Organic Sunflower Oil) for butter and includes the flavors of cranberries, pecans, cinnamon, nutmeg, and orange peel. I also substituted a 1/2 cup of organic blue corn meal for 1/2 cup of whole wheat pastry flour.

For some time, I’ve been sprinkling some grated organic orange peel in my morning oatmeal as it cooks, and a recent article in Parade Magazine (11/4/16) by Stacy Colino, Peel Appeal: The Nutritional Benefits of Fruit and Veggie Skins confirms this flavor boost to my breakfast oatmeal. Made sense for me to include orange peel in this recipe for cranberry pecan muffles as well, for the nutritional and flavor boost.

The muffins are tangy and delicious! But if you desire a sweeter muffin, I’d suggest substituting a 1/4 cup sugar for 1/8 cup of the maple syrup in the recipe. (Katie Webster in her cookbook, Maple- 100 sweet and savory recipes featuring pure maple syrup, recently reviewed on this website, recommends that if a recipe “calls for 1 cup of white sugar, use 3/4 cup of maple syrup.” In addition, she suggests decreasing other liquids called for in a recipe by about 3 tablespoons per cup of maple syrup. (Following this latter suggestion, I reduced the amount of cultured milk I used in the recipe to 3/4 cup instead of 1 cup.)

Cranberry Pecan Muffins (makes 6 large muffins)

Whisk together in a large bowl:

1 and 1/2 cups organic Farmer Ground whole wheat pastry flour

1/2 cup organic blue corn meal

1 tablespoon baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon ground organic nutmeg

1/4 teaspoon ground organic cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon of grated organic orange peel

3/4 cup pecans (broken up)

3/4 cup of whole cranberries (if particularly large, cut in half)

In another bowl, whisk together:

3/4 cup plain kefir cultured milk

3/4 cup of maple syrup

2 eggs

4 tablespoons sunflower seed oil

Add the “wet” ingredients to the flour mixture and mix until the dry ingredients are moistened but don’t overmix.

Divide the batter among the six muffin cups. I lined my beautiful Bennington Potters stoneware muffin pan with If You Care jumbo baking cups (certified compostable, unbleached and totally chlorine-free), which made for an easy clean-up.

Bake in an oven, preheated to 375 degrees (slightly reduced from 400 degrees recommended in Joy of Cooking) on the advice of cookbook author Katie Webster, who notes that maple syrup may cause baked goods to brown more quickly and decreasing the oven temperature by 25 degrees will usually help prevent that from happening.

The Joy of Cooking cookbook also notes that muffin pan sizes vary, and baking times vary with them. For a jumbo muffin, after 25 minutes, check for doneness by inserting a toothpick in 1 or 2 of the muffins and if it “comes our clean,” the muffins are done.

Let cool for 5 minutes before removing from the pan. Enjoy a special breakfast treat for Thanksgiving.

(Frank W. Barrie 11/23/16)

Lunch at Hilltop Café on The Temple-Wilton Community Farm in New Hampshire

Veggie omelette with spinach, caramelized onion, grated carrot, avocado & cheddar cheese served with home fries & toast, plus side order of bacon

Farm store open to the public, also sells Plowshare Farm organic oatmeal raisin cookies, perfect for the long drive home

Darcy Drayton’s wonderful watercolors, a teacher at Pine Hill Waldorf School, adorn the walls of the café, including a landscape of farm fields in Herefordshire, England

On a grey, mid-November day, with post-Election Day malaise prompting anxiety about the future, lunch at New Hampshire’s Hilltop Café in a cozy restored 1765 farmhouse on Abbot Hill (at 923 feet, the highest elevation in the rural town of Wilton in Hillsborough County) raises the spirits and rewards the taste buds. Committed to “using fresh, local and organic ingredients to create nourishing meals,” the Hilltop Café has a special relationship with the historic Temple-Wilton Community Farm which has been “Growing Food in Community since 1986.”

Christie and Ben Reed, who operate the café, are two members of the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. The farm assisted the Reeds in getting the local zoning board to approve their plan to operate the Hilltop Café, as a “natural extension” of a well-established farm stand according to an article by Amy Traverso in Yankee magazine (May/June 2014). The café opened in February 2011 and on its website notes that it is “a proud partner of the Temple-Wilton Community Farm.”

Before describing my wonderful lunch at the café, a few words are in order about the Temple-Wilton Community farm, “the oldest continuously operating CSA in the United States.” A diversified farm of 200+ acres, it grows and produces “everything from raw milk and cheeses to biodynamically-grown vegetables, pastured-raised meat chickens, pastured pigs, laying hens, grass-fed beef and veal and grass-fed lamb.”

An important mission of this website is the promotion of CSA farms, rooted in our strong belief that what we choose to eat requires that we know where our food comes from and how it’s produced because our food choices have serious consequences not only for an individual’s health, but also for the health of our communities and the planet. The Temple-Wilton Community farm is an enviable “community of people who care for each other as they care for the land that sustains us all” as noted on the farm’s home page. Moreover, this historic CSA farm places a special emphasis and faith in “community.”

Nearly all CSAs are seasonal and have a fixed price for a fixed share in the harvest. For example, this writer belongs to Roxbury Farm, a Hudson Valley CSA in Kinderhook (Columbia County in upstate New York), where for approximately $600, a shareholder receives weekly deliveries of freshly harvested, organic vegetables for 24 weeks.

The unique Temple-Wilton Community Farm CSA does not maintain “a direct relationship between the money needed to operate the farm and the produce that comes through the bounty of nature.” Instead, it asks its members to meet the expenses of operating the farm “by having each family pledge to contribute as much as they could manage.”

Another unique feature: members take what they need rather than a specific portion of the harvest. All members of the Temple-Wilton community farm accept responsibility for the agricultural use of the land and become “farmers.” They either farm directly, by planning and doing the farm work as “Active Farmers” or pledge to contribute to the operation of the farm based on “the ability to pay.” The farm’s Principles of Cooperation details the standards for the operation of this remarkable CSA “community.”

This community farm’s form of CSA is “rooted deeply in the social and economic ideas of Rudolf Steiner” in the words of Robert Karp, Co-Director of the Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association. Mr. Karp notes that farmers and eaters are not in a relationship of buying and selling produce. Rather members “are making gifts to support the continued existence of the farm as a whole and that the produce they receive in return is a gift.” Abbot Hill, where the farm is located, is also the home of two Waldorf Schools, based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, Pine Hill School (birth through Grade 8th) and High Mowing School (founded in 1942, the only Waldorf boarding school in North America).

Onward now to my pleasure in partaking of a delicious lunch at the Hilltop Café. With its appealing “Breakfast Staples” which are served all day, an omelette, made with two eggs, served with home fries and a slice of toast was a not-so-easy choice given the omelette possibilities. Instead of the delicious sounding one made with “eggs whisked with yogurt and herbs, filled with toasted pecans and feta,” I opted for the café’s veggie omelette made with an intriguing combo of spinach, caramelized onion, grated carrot, avocado and cheddar cheese. Delicious. And I’ll admit to ordering a side of two crispy slices of bacon which added to the pleasure of the meal.

The broccoli cheddar soup of the day, served with another couple slices of thinly sliced and toasted “sandwich French” bread from Orchard Hill Breadworks, added to this diner’s sustenance before a close to three hour drive, back home to Albany, NY. The café uses A&E Coffee Roastery’s organic espresso blend “shots”, added to hot water, for its Americano “espresso drink” which provided a boost in energy for the road trip. Served in a Voice of Clay coffee mug made by local potter, Wendy Walter, in Brookline (Hillsborough County, NH), it was a cup of muddy water worth savoring.

After the “surprise outcome” of the presidential election, Richard McCarthy, the Executive Director of Slow Food USA, sent a message to Slow Food members suggesting the need to pay attention to current politics but not to get “absorbed by them.” Instead, he reminded Slow Food members “to focus on the regenerative values of food and community.” It’s fair to say that in Wilton, New Hampshire, the Hilltop Café and the Temple-Wilton Community Farm are doing just that.

Not far from Nashua’s suburban sprawl and only 33 miles east of Keene, N.H., a drive into New Hampshire farm country to enjoy a meal at the Hilltop Café is highly recommended.

[Hilltop Café, 195 Isaac Frye Hwy, 603.654.2223, Breakfast & Lunch: Tues-Sun (closed Mon) 8:00AM-2:00PM, Also closed Tuesdays in winter; click on link to confirm operating hours, www.hilltopcafenh.com]

(Frank W. Barrie 11/18/16)

Food and Farm Conference Confronts Challenges Posed by Climate Change

Colonial Revival stone barn at Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, NY, one of the oldest rural life museums in the country

Dr. Laura Lengnick, keynote speaker at Food & Farm conference and author of Resilient Agriculture

Dr. Michael Hoffman, Cornell professor who researches “pest biology & ecology in vegetable crop systems”

For its third annual conference in its Celebration of Our Agricultural Community series, the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown (Otsego County in upstate New York) addressed Climate Change and Its Impact on Farming in Central New York. The bad news, of course, is that we are on an irrevocable path to an ever-greater crisis, a crisis that will be aggravated by unscientific responses to climate change likely to be embraced by the new political administration in Washington. The good news is that central New York – as with much of the northeast – won’t initially be as badly affected as the rest of the country, and already has made strides to address these problems.

“The experience of climate change is different in different parts of the country,” said Dr. Laura Lengnick, the keynote speaker at the all-day event held earlier this month. It’s not changing the weather the same amount in all parts of the United States. She noted that the frost-free season length has increased in the northeast by ten days, while the southwest has gained nearly twenty. “The growing season is increasing, but pests are also increasing,” she added. “Dormancy in plants is changing. So is the level of heat stress on both plants and humans.”

Lengnick has spent over three decades as a researcher and educator – and, not incidentally, a farmer. She spent ten years leading the sustainable agriculture program at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina, which she left to found the firm Cultivating Resilience to offer planning services to communities, businesses, and government. She’s also the author of Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate (New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2015).

“We as a species have never had to deal with a challenge like this,” she said. “We’re an adaptable species, which gives us hope – but the changes we’re facing may be the most dramatic we’ve ever seen. One source of hope is that we’ve spent the last forty years building a foundation of ecologically sound sustainable agriculture, tying it in with local economies.”

Asked how to deal with people who question climate change, she emphasize how much human beings love stories. “Sharing stories is how we make sense of things. Beliefs are far more easily changed through stories than with facts. Finding common ground, where values are shared, is the way forward. The stories have to be localized, personalized.”

Dr. Jason Evans addressed the issues from a policy angle. “Environmental damage is an external cost of production and consumption,” he said, “and when producers don’t take this kind of thing into account – as they won’t – they’ll overproduce. And that’s a waste of resources.”

Based at SUNY Cobleskill, the West Virginia native teaches courses in agricultural economics, agricultural policy, marketing, sales, and quantitative methods. He demonstrated the need and cost, undergirding policy decisions, by asking how many in the crowded conference room would pay a dollar a year to keep a polar bear alive. All hands, it appeared, went up – but as the annual price went up, the hands went down. “It’s hard to calculate value when you’re attaching that value to a feel-good concept.”

What does good policy look like? A Powerpoint slide gave some examples: It addresses the cause of the problem, leads to a more efficient allocation of resources, and exemplifies the most cost-effective approach. “But even without policy,” he said, “pure economics and better information will lead farmers to adopt better ecological practices.”

Drilling down to specifics, Dr. Todd Walter pointed out that in addition to getting warmer, we’re getting wetter. “And we have more extreme precipitation,” he said. But it doesn’t necessarily serve us when we need it, as the recent headlines-prompting droughts have shown. Thus, drought resilience is becoming another climate-change challenge.

Walter is director of Biological and Environmental Engineering at Cornell, and is able to turn theories into experiments, as in the work he’s doing with cover crops to stave off the effects of droughts and heavy rains, as well as enriching the soil. “We have opportunities to reimagine the system as a whole, and with that the potential for more positive solutions. For example, we have to look at more diversity of farming as a way of spreading the potential for risk, which can only be examined as part of a whole system.”

The conference’s afternoon session kicked off with a more comprehensive look at the science of climate change. Dr. Michael Hoffman, executive director of Cornell’s Institute for Climate Smart Solutions, emphasized the need for greenhouse gases, but showed some sobering slides describing the soaring measure of excess and its fallout.

Our temperature average has increased a degree and a half Fahrenheit, making it warmer at the poles. “Glaciers worldwide are retreating. The acidification of the oceans and the rise in sea levels are already having disastrous effects.”

With scientific analysis come reasonable prognoses, but the topic of climate change brings none of a reassuring nature. A mega-drought is so called when it lasts at least 35 years, “and there’s a 99 percent probability of a mega-drought in the southwest before 2100,” Hoffman assured us. “It’s no longer business as usual. With more variability comes more risk, and local impacts have global consequences.”

Meeting these challenges, he said, will require more resilient crops, which even now are being studied through the use of drones that can record the height, reflectiveness, and starch content of plants in a field, along with renewable energy sources and other sophisticated tools – a number of which can be found at http://climatesmartfarming.org including calculators for Growing Degree Days, Water Deficit, and Nitrogen Management.

“In general terms,” he concluded, “local is better, but even lettuce coming here by rail from California has a relatively small footprint. And – you won’t like this – try to eat less meat.”

The finish of the conference became much more technical, offering practical advice for the farmers among the crowd. Lengnick returned with strategic approaches to managing climate risk, dividing it into three basic strategies: resistance, resilience, and transformation. Resistance calls for using financial and physical assets to reduce exposure risks, while the more potentially successful resilience practices include a diversification of production and better management of a farm’s ecosystem processes. Transformation, the most radical, includes moving from annuals to perennials or, at least, inter-cropping them, and moving from a concentrated animal feeding operation to a more integrated approach that includes pasture-based and even multi-species grazing.

“All of it is completely do-able,” she said. “It’s already being done all over the country, and it’s being done in some way or other with all the types of food we eat.” Lengnick’s book, Resilient Agriculture, is the result of time she spent with over two dozen farmers around the country, “farmers who made changes on their own, with no government help, but wth their own supportives families to depend on.” It’s that combination of science and local innovation that’s going to save us in the years ahead.

(B.A. Nilsson 11/11/16)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): We previously reported on food activist and writer Mark Bittman’s appearance last year at the State University of New York at Albany’s Writers Institute where he noted that success for him would be to get every American to eat rice and beans at least once a week. A goal that comports with Dr. Michael Hoffman’s suggestion to “try to eat less meat.”]

Sweet & Savory Recipes Featuring Pure Maple Syrup

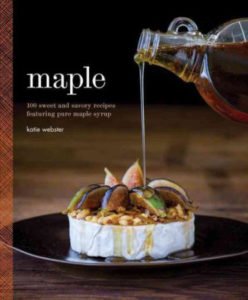

Katie Webster’s Maple, 100 Sweet and Savory Recipes Featuring Pure Maple Syrup

One of North America’s gifts to the world is maple syrup. The earliest history of the process of boiling down maple sap to extract sugar is unknown but early European explorers and settlers observed native Americans do so and soon emulated them.

By the early 18th century the conversion of sap to rock maple sugar was common in Canada and the northern states. In the early 19th century production had become so widespread that Quakers and abolitionists urged the use of maple sugar as an alternative to plantation sugar cane produced by slave labor. The initiative was supported by Thomas Jefferson who planted maples at Monticello in an effort to produce his own sugar (he was not successful).

The 20th century produced the invention of flexible tubing and vacuum pumping as well as enhanced methods to extract water from the sap which realized greater efficiencies and increased production. The process remains, however, relatively straightforward and today most maple syrup is produced by small, family-run businesses.

Which brings us to Maple, 100 Sweet and Savory Recipes Featuring Pure Maple Syrup by Katie Webster (Quirk Books, Philadelphia, PA, 2015). As pointed out in the book’s foreward by Molly Stevens, food writer and cookbook author, what could be better than a sweetener that comes directly from the woods, is naturally sustainable and contains nothing but fresh sap boiled down to a delicious syrup? If more persuasion is needed, Katie Webster points out that maple syrup is not stripped of its micronutrients during production (unlike refined sugars). For those concerned about sugar intake, the good news is also that less maple sugar than white sugar is required to sweeten a recipe, a point reinforced throughout the book.

Maple abounds with not only breakfast recipes, as one might expect, but also a wide range of maple-flavored recipes for appetizers, soups, salads and main courses. The latter include dishes such as maple/ginger chicken thighs, maple pork loin roast and sweet and sour cabbage rolls. Who knew there was so much more to pure maple syrup than serving as a delicious accompaniment to pancakes or glazing for yams?

Not surprisingly there are several cookie and dessert recipes – and even a couple for drinks such as maple peach old fashioned and the charmingly-named mapletini – which comes nowhere near a classic martini but, if Katie Webster is to be believed, should make no apologies for that.

Each recipe is clearly and simply set out with Katie Webster’s own superb food photography illustrating the recipes. Webster’s photos are complemented by Kristy Dooley’s natural light, on location photographs of the late winter tapping of maples in the still snowy state of Vermont, well-known for its maple sugaring tradition.

Every recipe includes a friendly hint or advice from the author. An example, a recipe for a classic French dessert, clafoutis, counsels against panic when it threatens to puff out of its pan while baking: it won’t but will fall back into place as it cools. That’s the sort of reassurance that will alleviate the worry of many unfamiliar with the exuberant behavior of clafoutis in the oven.

Although this is not a book that tilts towards science, there is an informative chapter on the chemistry of maple sugar, which is useful to develop an appreciation of how it reacts differently from refined sugar. It also contains a handy guide to the different grades of syrup as well as helpful pantry notes and a list of resources.

There is also an index that employs the symbols G, V and P to identify specific recipes for the guidance of those on gluten-free, vegan or paleo-friendly diets. For the very adventurous, there are even hints on backyard production, including a reminder that it takes about 40 gallons of sap to make a gallon of syrup: it is thus not an operation for the faint-hearted. Finally, a comprehensive conversion table of US measures to metric (volumes, weights and oven temperatures) would make the book an ideal gift from America to overseas.

Maple provides a straightforward overview of maple sugar in its various forms and uses, delivered in a very attractive package. Not to mention that it makes for an exquisitely mouthwatering read!

(Eidin Beirne 11/10/16)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): In an earlier book review, we noted that Rowan Jacobsen in his instructive and entertaining American Terroir leads off with a chapter on maple syrup because it is so uniquely American and, like wine, has remarkable “terroir.” Jacobsen writes of his discovery of a maple syrup which is “rich, creamy and sweet but not cloying” as if “somebody had melted a pad of sweet butter in it.” We also reported last year on the revised grading of maple syrup by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) which now categorizes Grade A maple syrup in four color and flavor classes: golden and delicate; amber and rich; dark and robust; and very dark and strong. And also encourage a visit to our web page for Maple Syrup, which includes a link to Sugarbush Info, which maintains listings of over 500 maple syrup producers (sugar bushes) in the U.S. and Canada, as well as listings for 13 maple syrup festivals in Canada and 14 in the U.S.]

Food Festival’s Moveable Feast Fortifies Local Farm Economy & Community Rebuilding

60 guests dined at homes of participating hosts including Schoharie village home of Emily Davis & Mike Warner

Kuhar Family Farm hosted a dinner at Middleburgh’s Dr. Best House and Medical Museum, which had historical artifacts on display

There’s no good time for a flood, but late August has to be the worst for a farming community. The Schoharie Creek ran up over its banks when Hurricane Irene hit during that time of year in 2011, punishing the area in and around the town of Schoharie in upstate New York, with a disaster that killed livestock, ruined crops, and left homes and business under water. Along with governmental assistance came help from the community, and one group, calling itself Schoharie Recovery, plunged into the thick of the disaster with food for the displaced residents. It was a successful enough program to suggest that there was cause to continue even after the damage had been cleared, and Schoharie Area Long Term (SALT) Development was formed.

“Five years later, we’re still looking for new ways to move forward,” said Emily Davis, one of the dinner hosts participating in the Savor Schoharie Valley local food festival’s moveable feast, which raises funds for the continuing effort to rebuild and develop the rural economy in Schoharie County of upstate New York. “The valley has always been oriented towards food. We have the Carrot Barn, the Apple Barrel Country Store, and so many individual farmers.” SALT held its third annual Savor Schoharie Valley festival on Saturday, October 22, a blustery evening laced with rain that reminded us of the area’s seasonal volatility.

The festival is a fund-raiser that introduces people both to the county’s food and to its hospitality. The event began and ended at Schoharie’s Lasell Hall. This is an imposing 18th-century tavern in the village center, a building now owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution who, several decades ago, established the town’s first library here, and who more recently restored the lower-level of the house from the damage it sustained in the flood.

Like most houses of that age, it’s a warren of small rooms and many hallways. The main gathering room, to the right of the hallway, featured a number of appetizers that included meatballs from Hubie’s Restaurant & Pizzeria, crudité from the Apple Barrel Country Store, bruschetta from Chieftains Restaurant, and fast-vanishing potato balls from the Bull’s Head Inn.

Smaller rooms both downstairs and up shared photos and souvenirs from several Schoharie County towns, with historians on hand to further your acquaintance with these places – like Blenheim, a town in the southern part of the county that boasted the longest (210 feet) single-span covered bridge until Irene’s flooding completely destroyed it. “It’s being rebuilt,” historian Gail Shaffer explained. “We have the original blueprints, and it’s going to be re-created as accurately as possible.”

With the centralization of so much of the area’s farming and manufacturing, these towns tend to embrace whatever history persists in old ledgers and faded photos. At the upstairs table where Jefferson historian Ingrid Zeman sat were two program booklets from that village’s Maple Festival, which began on a green surrounded by 120 maple trees. But, even as Jefferson shared a table with Cobleskill, so too was the Maple Festival sent several years ago to the larger Cobleskill fairground. If there’s a single lesson to be learned from this evanescent history, it’s that nothing remains the same.

But this is being turned into an asset by SALT’s project director, Laura Morace, who is spearheading the country’s Trails to Tales project. “It’s a website and mobile app that showcases creative and recreational assets throughout the county,” she noted, “exploring the bounty that’s found along the Route 30 corridor.” It’s a bounty that includes plenty of food, and the Savor Schoharie County participants showed their partisanship. “We’re trying, on a regular basis, to use only food that we can find within fifteen miles,” said Davis, adding, with a laugh, “although I’m not prepared to give up bananas or coffee.”

My wife and I dined at the home that host Davis shares with Mike Warner, located on a high-enough hill to have escaped damage five years ago, although they nevertheless helped to spearhead the area’s food relief back then. And they’re still cooking: squash for the soup that started off our meal came from nearby Schoharie Valley Farms (known to locals as the Carrot Barn), which also supplied the potatoes (mashed with Cowbella Dairy butter from Jefferson), carrots (more butter), cabbage for the salad, and onions for everything. Even the meat was local, with beef short ribs from Schoharie’s Wrighteous Organics. Garlic and herbs were supplied by Fox Creek Farm in Gallupville, and apples for the cider were harvested right on the property.

It was a similar story at the other hosting houses. Paul Turner & Dee Pendell cooked and served a meal at the Schoharie home of Georgia VanDyke that included chicken from Cobleskill’s Abbas Acres, corn (for chowder) from Cold Spring Farm (Lawyersville), bacon from Sap Bush Hollow Farm (West Fulton), potatoes and onions from Summit Naturals (Summit), Sharon Orchards McIntosh apples (Sharon Springs), Buck Hill Farm maple syrup (Jefferson), peppers from Shaul Farms (Fultonham), and KyMar Farm Winery apple wine (Charlotteville).

Abbas Acres also supplied the chicken served with the gluten-free fare prepared by David Chancey and Doug Guevara, with Chancey’s own garden the source of produce served both fresh and pickled, and free-range eggs from right next door. Richard & Marilyn Wyman showed that local can be exotic by preparing a cream of shiitake soup with their own mushrooms, and moussaka with eggplant from Barber’s Farm (Middleburgh) and lamb from Hessian Hill Farm in Berne.

Kuhar Family Farm is across the county line in Rensselaerville (Albany County), but that didn’t stop them from participating. They offered a choice of pork sausage or meat-free lasagna at the historic Dr. Best House and Medical Museum in Middleburgh, where guests dined in a beautiful, dark-paneled room that featured, as a table decoration, a skull from Dr. Best’s collection of anatomical examples.

Back at Lasell Hall, we compared notes with other guests – there were about 60, not counting hosts and historians – and sampled a range of tasty sweets, including chocolate cupcakes, made with stout from Middleburgh’s Green Wolf Brewing Company, by Lucky Clover Artisanal Bakery, who also use organic flour from the northwest part of the state. Zucchini from Schoharie Valley Farms went into sweet zucchini bread and the apple cake had fruit from Schoharie’s Terrace Mountain Orchard. And even if the coffee beans are from afar, they were roasted in Middleburgh by Democracy Coffee, a company with a mission. Its People’s Empowerment Project is dedicated “to restoring democracy by eliminating the corrupting influence of money in our political system.”

Of course, buying any of your food locally has a political component because you’re fortifying the economy of your neighborhood. It also tends to be healthier and, as this event proved, there are fascinating resources and history to be discovered in and around those nearby farms.

(B.A. Nilsson 11/1/16)

[Editor’s note (FWB)- Many of the farms and local food producers noted above are associated with Schoharie Fresh, an on-line farmers market based in Cobleskill.]