Twenty-five years ago in 1991, a houndy looking lab, with some golden retriever thrown in, wandered into Ted Kerasote’s campground along the San Juan River in Utah, about 100 miles down the road from Moab. This 10 month old, half-wild mixed breed, named Merle by Kerasote, became his loving companion in a person-dog relationship that would last for a too-short 13 years. Merle died of glial cancer in 2004.

Ted Kerasote, during his four decades career of writing and photography, has written on the interrelationship of people, animals and the natural environment. In this fine writer’s words, he discovered the sweetest remedy for grief by snatching Merle from time’s dissolution and turning him into story. Kerasote sifted through his memories and steadily wrote over a period of nearly three years. His national bestseller, Merle’s Door, Lessons from a Freethinking Dog (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008) touched the hearts of many readers and earned the respect of dog lovers, including Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, author of The Hidden Life of Dogs, who said it could be the best book ever written about dogs.

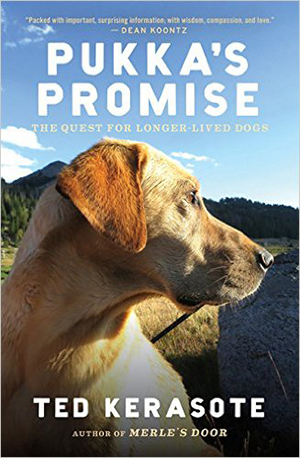

Kerasote writes in his latest book, Pukka’s Promise, The Quest for Longer-Lived Dogs (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) that Merle’s death “had inoculated me against any other dog for years. . .” But in 2008, four years after Merle’s death and after the publication of Merle’s Door, he decided: “I wanted no empty couch. I wanted no silent house, I wanted another dog in my life.” Closely tied to this desire for another canine companion, Kerasote embarked on a mission to learn about the “healthiest ways to raise our dogs and to find my own new dog.”

Kerasote’s quest to find out why dogs die so young (only 1/8th the human life span) was also prompted by the hundreds of e-mails, “many of them heartrending,” he received from readers who had lost beloved dogs. In particular, readers questioned why their dogs were dying of cancer, mirroring Kerasote’s concern:

“Merle’s best friend Brower, a Golden Retriever, was diagnosed with a malignant cancer of the snout when he was six. Another of Merles’s good friends, a black Lab named Pearly, died at seven of a neurofibrosarcoma that began in a nerve root at the base of her neck. Merle himself, though no young dog at fourteen, finally succumbed to his brain tumor.”

Kerasote’s search for his new dog, detailed in his latest book, reflects the laudable work of an accomplished and thoughtful writer, assisted by six researchers. Pukka’s Promise (Pukka meaning “first class” in Hindi) tells not only a terrific story, but, with its 49 pages of footnotes, rises to the level of a reference book for anyone seeking guidance on how to find, raise and love a canine companion. As noted by Jon Katz, the author of A Good Dog, Pukka’s Promise “stirs our hopes for the future.”

Domestic dogs in the United States, estimated to number somewhere between 60 to 77.5 million, share 99.9% of the DNA of wolves. In the wild, wolves live no more than three or fours years, while in the safety of captivity, wolves can live as long as a big domestic dog, from 12 to 14 years.

Kerasote notes the differences in longevity among dogs, with small and medium sized dogs living longer than large ones (which die often before 10 years old) can be genetically explained. In the mid 2000s, it was discovered that all small dogs have a tiny mutation of the gene called IGF1 and produce less of the protein IGF-1, than larger dogs, so that insulin levels of smaller dogs fall and life span increases.

But it’s not only genetics that determines the life span of dogs. The following seven factors, which Kerasote thoroughly examines, affect dog health and longevity. And they provided the basis for his decision on what dog would become his companion and how he would raise his new canine friend: inbreeding, nutrition, environmental pollutants, vaccination, spaying and neutering, the shelter system in which too many dogs end their days and the amount of freedom dogs enjoy.

Kerasote notes that a great number of people believe it’s morally wrong to do anything but adopt a dog given that 1.5 million healthy dogs are put to death each year in American shelters. But he knew if he got a dog from a shelter, it would almost certainly be spayed or neutered, “potentially reducing my chances of giving it the longest life possible.” According to his research, spayed and neutered dogs experience more adverse reactions to vaccines, a higher incidence of some cancers, suffer more orthopedic injuries, have a greater propensity to endocrine dysfunction and are more obese. Kerasote is an ardent advocate for vasectomies and tubal ligations, which allow a dog to retain its beneficial sex hormones, as alternatives to spaying and neutering.

Because mixed-breeds or crossbreeds don’t make breeders much money, Kerasote couldn’t find a single breeder turning out a houndy looking lab, and he turned to breeders of labradors. He needed “a big enough dog to join on hikes, climbs and mountain biking trips in summer and big enough not to be coyote bait.” He also sought a dog that would be calm and intelligent, love the cold and high places, and could navigate deep snow without its paws clogging. A labrador could potentially fit the bill for a rangy, athletic dog that could track well (a dog’s extraordinary sense of smell is up to 100,000 times more acute than a human’s) as retrieve. It’s fascinating that Kerasote’s final test in selecting Pukka from a litter of pups is his own sense of smell: “The darker pup smelled rich-like lanolin with a hint of nuts-a faint remembrance of Merle, of hounds, of Golden Retrievers. . . I wondered if on some unconscious level, some pheromonal level, I had been drawn to the darker pup for this very reason. I’ve alway trusted my nose when it comes to decisions of the heart. . . among all our senses the most difficult to fool.”

Given his decision to find a breeder of labradors with a pup that would meet his needs, Kerasote’s discussion of the health consequences of inbreeding were of particular significance:

“Selecting for certain characteristics in dogs. . . not only produced dogs with differing life spans. It also caused dogs of every size and shape to be more inbred and thus prone to a variety of genetically linked diseases. About four hundred of these conditions have now been cataloged in purebred dogs. . . .” One striking example: 100,000s of North American Golden Retrievers are descended from three champions and have received both their sweet dispositions and their hidden time bombs: a survey conducted by the Golden Retriever Club of America and the Purdue School of Veterinary Medicine notes that 61.4 percent of Golden Retrievers die of cancer.

Kerasote discovered that it was “easy to find out,” by calculating the coefficients of inbreeding (COIs), how inbred (and therefore how potentially disease-prone) a litter of pups might be. By using a computer program from PedFast Technologies that cost a little more than $10.00, his goal “was to find litters who had COIs of less than 6 percent.” One nonrandomized survey of Standard Poodles found by Kerasote that contained 349 records showed poodles “who had a COI of less than 6.25 percent lived nearly four years longer than those dogs whose COI was greater than 25 percent.”

Also important when buying a pup is to visit the place where it was bred in order to evaluate the puppy’s temperament. Kerasote writes: Interacting with the parents of your prospective puppy as well as its breeder can tell you more about what sort of dog you’re going to live with.

Of the seven factors, noted above, analyzed insightfully by Kerasote, of special interest to this reader was his advice on a dog’s nutrition. He notes that it is not cheap to provide healthy, nutritious food to a dog. In the first year and a half, as Pukka went from a fourteen-pound puppy to a seventy-pound dog, and when he was “the equivalent of a rapidly growing teenager- he would eat between five and seven pounds of meat, bones, and vegetables in a day . . . or 9 to 13 percent of his body weight.” Kerasote estimates the yearly cost of $2,500 for his preferred commercially prepared, AAFCO-certified raw food diet, “almost all of whose ingredients are free-range and organic.” He understands that, according to surveys by the American Pet Products Association, the average American spends $229.00 per year- 67 cents per day, on dog food, and that a popular kibble from a big-box store certified by AAFCO, would cost even less than that average, at $150 annually. However, that would mean a beloved dog would be fed a kibble “whose first ingredient is corn and which also contains wheat middlings, soybean meal, brewer’s rice, and animal fat preserved with BHA, along with the artificial colors yellow #5, yellow #6, red #40, and blue #2.”

Pukka’s Promise includes nearly 70 pages focused on a dog’s diet organized into four insightful chapters. Kerasote cites to the writings of three veterinarians, Dr. Ian Billinghurst, the Australian founder of the raw food movement, Dr. Marty Goldstein, a champion of raw-food diets, and Dr. Karen Becker, who started the widely read website Mercola Healthy Pets, as well as Ann N. Martin, the author of Foods Pets Die For (who it has been said by Dr. Michael Fox “is to the pet food industry what Rachel Carson was to the petro-chemical-pesticide industry”).

Chapter 12, Carnivore to Monovore, begins by noting what real wolves eat: the answer short and simple, wolves are 98% carnivore. Then applying a fascinating, historical perspective to his analysis, Kerasote cites the 19th century, Scottish-born medical doctor and dog fancier Dr. William Gordon Stables, who cautioned against overfeeding grains. But Stables didn’t limit a dog’s diet to meat, and was “adamant” that “dogs needed vegetables at least three times a week: cabbage one day, kale the next, then turnips, and so on.” Kerasote’s description of the beginnings of the commercial pet food industry shows that “marketing and advertising” early-on justified replacing a diet of raw meat, bones and vegetables with manufactured biscuits and specialized dog foods made with “what other industries considered their waste products-grain husks, meat trimmings, worn-out livestock, dying draft animals.”

With a critical eye applied to the over $15 billion dollar pet food industry, as well as vivid descriptions of his visits to rendering facilities and his frustrated attempts to tour the facilities of major manufacturers of dog food kibble, Kerasote rejects high-carbo, corn-based kibbles, which raise blood glucose levels quickly. He cites research that demonstrates that reducing the amount of starch in canine diets helps to manage problems of canine obesity and diabetes. Reducing “the inflammatory chain reaction,” which leads to degenerative diseases associated with aging (such as cancer, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, allergies and autoimmune disease), can be achieved with a diet that includes, for example, raw meaty bones, chicken carcasses, and ample green leafy vegetable citing the advice of Dr. Billinghurst.

In a later chapter, Real Food, Many Forms, Kerasote’s summarizes his decision to feed Pukka an AAFCO-certified raw food diet, with one major caveat. He describes testing three commercial kibbles, five commercial, frozen raw-food diets and two dried ones for lead, and found no detectable level of lead in only three. His concern about heavy metals in foods, dog or human, confirmed by this testing, reinforced the wisdom of what Dr. Joe Bartges, on the faculty of The College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Tennessee, told Kerasote: to rotate a dog’s food so as “minimize the risk of feeding the same heavy metals year after year.”

The Cornucopia Institute, which supports ecological principles and economic wisdom as it advocates for sustainable and organic agriculture, deserves much credit for developing a Pet Food Guide. In a recent newsletter, the Institute pointed out that “Pet food quality varies significantly and all too often includes dangerous chemical additives.” Kudos to the Institute for its “thorough analysis of the pet food industry” and its report and guide to pet food. Also appreciated is the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) recent bid to regulate animal food (reported in the New York Times by Sabrina Tavernise), acting for the first time, after recall and deaths. Since 2007, the FDA has counted about 580 pet deaths, nearly all dogs connected to jerky treats, nearly all imported from China. Dog lovers can remember well the biggest pet food recall in history in 2007 when a Chinese producer contaminated dog and cat food with melamine, a compound used in plastics, causing the deaths of animals across the United States.

As a closing note, this past summer, Ted Kerasote announced to his “friends and readers” that the “moment may happen soon” for Pukka to sire a litter, and he is seeking a suitable mate: “a dark yellow or fox-red Labrador Retriever, who has completed all her health certifications.” He has created a website, www.breedingpukka.com, which contains all the relevant information needed for breeders to see if Pukka is a good match for their female. Might a new book be gestating in Kerasote’s mind too? For his readers, let’s hope so.

(Frank W. Barrie 2/9/16)