Archive for May 2018

Inspiring Vision For Restoring The Soil That Feeds Us: David Montgomery’s Growing a Revolution

David Montgomery’s Growing A Revolution, Bringing Our Soil Back to Life is a clarion call to restore the soil that feeds us all

A roller-crimper can transform a cover crop into an effective mulch, suppressing weeds, by laying the cover crop over in one direction and crimping or crushing its stems

Spring – planting season – isn’t a good time to read David R. Montgomery’s Growing a Revolution (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2017). Not when you live, as I do, in farming country in upstate New York. The plows are at work everywhere, from large green motorized behemoths to the horse-drawn antiques of the Amish. And, according to Montgomery, this is what not only has been destroying farmland around the world, it also probably was responsible for destroying past civilizations.

Montgomery sounded a death-knell over a decade ago in his book Dirt, which took a wide-eyed trip through a history of soil erosion and nutrient eradication, the long-range after-effects of what we thought too easily was progressive agriculture. It stands alongside Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature as a call for action falling largely on deaf ears, so Montgomery has revisited the topic in an encouraging, inspiring way. The needed changes can be made, he argues, and are being made – and in the unlikeliest places.

Growing a Revolution follows the author from country to country, climate to climate, to look at successful examples of no-till farming. As Montgomery is quick to observe, farmers generally aren’t given to change anything unless confronted with evidence of success, and that success needs to be seen in the harvests.

The key to Montgomery’s argument is conservation agriculture, the three components of which are (1) minimum disturbance of the soil; (2) growing cover crops and retaining crop residue so that soil is always covered; and (3) use of diverse crop rotations. These principles can be applied anywhere, on organic or conventional farms, with or without genetically modified crops.

The invention of the plow gave us cheap, reliable weed suppression, even as it destroyed the teeming world of earthworms and fungi and micronutrients that keep soil viable. Plant roots, Montgomery explains, are two-way streets through which carefully negotiated and orchestrated exchanges occur. Plants absorb nitrates and other soluble nutrients, and release carbon-rich molecules to feed fungi and bacteria that draw nutrients from the soil. You can learn much more about this from Montgomery’s previous book, The Hidden Half of Nature, co-authored with his wife, Anne Biklé, and reviewed here.

The large-scale manufacture of fertilizer worsened the problem, creating a dependency cycle that keeps those factories humming – and the dark secret behind them is that those factories can quickly be converted to munitions production, which ensures that they get federal financial support. Thus have we degraded a third of the world’s agricultural land – and it’s a failure that resonates through history.

Examining the archaeological record for ancient Rome, it’s clear that after the conquest of Carthage, when slave labor became plentiful, the landscape changed from small family farms to huge plantations, with the result of tremendous soil erosion and the eventual collapse of a civilization. There was massive soil erosion in colonial America thanks to tobacco farming, but that was at a time when there seemed to be no end of fresh land. It turns out, argues Montgomery, that there is an end.

Thus the simple, straightforward message of his conversational, well-crafted book, backed by centuries of common-sense farming. But we’re dealing with decades of quick-fix evangelizing, which keeps the chemical-fertilizer and herbicide makers wealthy, and the aforementioned class of stubborn individualists, whose plows large and small are in gear at the start of the 2018 growing season. So Montgomery takes us on a tour of farms where no-till techniques have been proven.

We meet third-generation no-till farmer Guy Swanson in a Kansas workshop, who notes that companies that control the fertilizer industry are functional monopolies. In the United States … Koch Fertilizer dominates production of nitrogen fertilizers, and the Mosaic Company (a spinoff of Cargill) is the largest producer of phosphate and potash fertilizers. He also focuses attention on Monsanto, makers of Roundup (glyphosphate), which has a monopoly on patented seeds for glyphosphate-resistant crops.

Writing about Swanson, Montgomery observes, On an irrigated no-till farm with a corn-corn-wheat-corn-sunflower rotation, his system reduced a $200-per-acre conventional fertilizer bill to less that $100 an acre. And it saved $25 to $60 an acre on dryland fields planted half in wheat and half in corn. If applied to a 10,000-acre farm, this adds up to an annual net savings of more than a quarter-million dollars a year. These are the dollars-and-cents figures farmers need in order to be persuaded, and they’re here in the book, calculated at each of Montgomery’s stops.

Wes Jackson founded the Land Institute in 1976, and is a celebrity pioneer of the sustainable agriculture movement. What he’d like to see on the prairies is an herbaceous polyculture founded on perennial grains instead of animals, in a bid to fight perennial erosion. After years of development, he’s now marketing one such grain called Kernza, which eventually should have a yield on a par with annual wheat.

A visit to Dwayne Beck, director of Dakota Lakes Research Farm near Pierre, South Dakota, looks at crop rotation. There’s no single best way, according to Beck – you have to develop your own based on location. His advice: Water use must match water availability. Crop diversity and ground cover are necessary for fending off weeds, pests, and disease. Crop rotations must not be consistent in either interval or sequence.

Jerome Rodale created Organic Gardening and Farming magazine in 1942, offering information about what he’d already put into practice at his Pennsylvania farm. His son Robert now runs the Rodale publishing empire and the 333-acre Rodale Institute, where they practice what they preach. Farm manager Jeff Moyer identifies weeds as the biggest problem, and uses a roller-crimper to crush the cover crop and thus block weed growth. Used with a planter, it allows the farmer to drop seeds into fresh mulch. Because of the persistence of perennial weeds, Moyer tills about every third year, terming it rotational tillage.

The US Department of Agriculture and a handful of universities saw the Rodale results and set up their own organic test farms. A 2015 review … found that organic practices proved economically viable (comparably or more profitable) and resulted in improved soil quality, greater soil carbon capture, and better pest suppression. But, as Moyer observes, farmers aren’t converting to organic methods because of the perceived protection of crop insurance.

The roller-crimper works best with a flowering cover crop, says North Dakota farmer Gabe Brown, but his growing season is too short for his cowpeas to flower before the corn has to go in. So he uses cattle to tear up the foliage. The aboveground chewing, tearing, and trampling by livestock grazing creates wounds that the plants must heal, writes Montgomery. “But the plants don’t do it alone. They need soil micronutrients and microbial metabolites – both of which will be delivered only if they pump a steady supply of carbon-rich exudates out of their roots to recruit microbial assistants.”

Montgomery’s world tour included a visit with Rattan Lal, a native of Punjab who earned his Ph.D. at Ohio State University in 1965 at the age of 24. After conducting successful experiments at the University of Sydney, Lal was hired by Nigeria’s International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, where he introduced no-till farming. Although the board chairman called it madness, within five years, Lal was vindicated by success.

Herbert Bartz experimented with reduced tillage in southern Brazil in 1970s, and kicked off what became a conservation agriculture movement in South America – which now is approaching total no-till in Argentina and southern Brazil. Ironically, it was helped by Monsanto’s Roundup for weed control, although many farmers are now adopting the other two conservation agriculture principles.

In Ghana, Kofi Boa runs the No-Till Center, where he’s known as Mr. Mulch for the cover crops he grows – green manure, he calls it. He’s fighting a history of studies in Africa that don’t see no-till as an effective solution – but the studies are flawed insofar as they don’t reflect all three components of conservation agriculture. In Costa Rica, Montgomery meets coffee farmers using biochar, a charcoal produced in smoldering fires, as a soil amendment. Inert but highly porous, it’s excellent for holding water and providing a microbial habitat. Peter Kring, an expatriate American who has lived in Costa Rica for many years, turned an abandoned cacao farm into a thriving one, with additional fruits and spices.

Also at issue is the matter of returning organic matter from cities to farms, which merits its own chapter. Milwaukee has been selling biosolids to farmers for a century; Denmark recycles more than half its sewage sludge, while Canada is recycling a fifth and the U.K. twice that amount. Montgomery visits a Tacoma sewage treatment plant visit that produces TAGRO, a microbially digested fertilizer, mixing biosolids, sawdust, and sand.

Controversy bubbles over what’s in such biosolids and how it’s applied, especially regarding heavy metal and pathogen content. Montgomery is fairly dismissive of the contamination potential, but he seems to be guided by a pair of reports that asserted low risk potential – although the studies themselves aren’t summarized. This issue hit home recently, as my hometown of Glen (Montgomery County) in upstate New York, recently was approached by Canada-based biosolids company Lystek to install a treatment facility in a nearby industrial park. This led to a very vocal outcry from some residents, a huge hearts-and-minds campaign by Lystek, and, ultimately, a rejection on the basis of legal technicalities.

Much of the information in Growing a Revolution grows repetitious – don’t till, plant cover crops, rotate, repeat – but Montgomery clearly is aware of this, and thus dresses his chapters with good humor and diverting anecdotes. I can’t see how he otherwise could write so persuasively about the subject.

At this point, only about 11 percent of global cropland is under conservation agriculture. Three-fourths of that is in the Americas. Very little of it is in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The revolution is coming more and more to the mainstream, as in a New York Times Magazine piece titled Can Dirt Save the Earth? (4/18/18) by Moises Velasquez-Manoff, and covers much of this ground. But it needs to spread to the fields, until the day we can all celebrate spring with the sight of lush, arable, unplowed fields.

(B.A. Nilsson, 5/29/18)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): A study recently published in Science Advances, the on-line publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (the world’s oldest and largest general science organization), has found that rising carbon dioxide levels this century will alter the protein, micronutrients and vitamin content of rice, which two billion people worldwide rely on as a primary food source. According to reporter Brad Plumer in a recent article in the NY Times (5/23/18), With More Carbon Dioxide, Less Nutritious Food, this recent study builds on a major study published in Nature in 2014, finding that elevated levels of carbon dioxide reduced the amount of zinc and iron found in wheat, rice, field peas and soybeans. This recent study bolsters the case for regenerative agricultural methods spotlighted by David Montgomery in Growing A Revolution. Bringing our soil back to life can heal damaged environments, improve farmers’ bottom lines and ensure the nutritional quality of food. And thanks to David Montgomery for making the very strong case for a path forward for agriculture that can be simply put. No-till farming: Allow plants to put down roots so they can absorb CO2 from the atmosphere.]

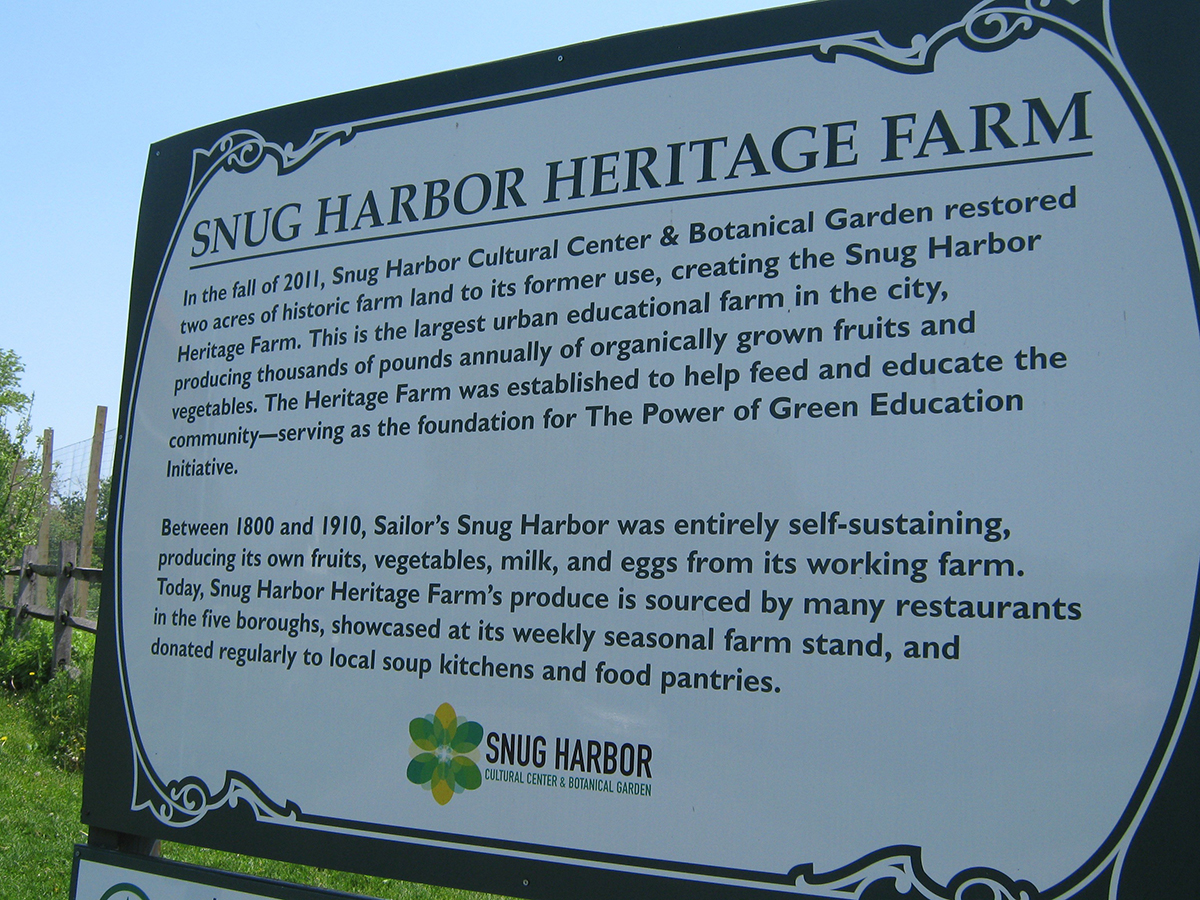

A 2.5 Acre Heritage Farm Grows In NYC: Producing 45 Tons of Produce In Past 6 Seasons & Growing Community Spirit

Historic farmland was restored in NYC to create the bountiful Heritage Farm at Snug Harbor on Staten Island

The feathery leaves of fennel plants signal a future summer harvest of this mildly anise or “licorice” flavored vegetable, a favorite of connoisseurs

The Heritage Farm is also a compost demonstration site for NYC’s Compost Project

A ride on the Staten Island (which is free!) from lower Manhattan to NYC’s island borough, plus a 15 minute City bus ride takes a visitor to The Heritage Farm at Snug Harbor

This spring. farmer Jon Wilson’s plan to plant 500 tomato seedlings was delayed by the heat of a day in mid-May that felt summer-like. The planting by a team of four farmers (two full time, two part-time) would have to wait until the cooler evening.

Farmer Wilson’s favorite tomato of the 36 varieties that would be planted this season is a big and wide Striped German, described by the experienced grower as low acidity, high brix, and citrusy flavored. The rich soil of a New York City farm, Snug Harbor’s Heritage Farm, on the western side of Staten Island (not far from where the Staten Island ferries dock in St. George after traveling over from lower Manhattan) would be demonstrated, later in the 2018 growing season, by the tastiness of eating a locally grown tomato.

Jon Wilson’s description of his favorite tomato reminded this backyard gardener that too few folks appreciate that tomatoes come in a multitude of varieties with varying flavors, and that freshness, ripeness and terroir (a characteristic taste and flavor imparted by the environment in which vegetables are grown) also impart qualities to a tomato, lacking in nearly all supermarket ones.

Farmer Jon Wilson and his team nurture the small city farm. This season, 20,000 square feet of cover crops (oats, peas and rye) were grown to enrich naturally the land.

Chefs from over a dozen New York City restaurants (in Staten Island, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, including Chef Thomas Keller’s internationally famous and very expensive Per Se (in the Time Warner Center on Columbus Circle in the heart of Gotham) who value the variety of flavors of heirloom tomatoes and other produce, have partnered with Snug Harbor’s Heritage Farm to make its 2.5 acres a local, agricultural success story.

And it’s not only big city chefs who benefit from the rich farmland. The small farm is committed to producing accessible, locally-grown produce for the community.

Seasonal produce is sold at the Heritage Farm Stand on the south side of the Snug Harbor campus, between the farm and the South Meadow. The farm stand is open 10:00AM-3:00PM every Saturday from mid June until Thanksgiving.

Snug Harbor’s Heritage Farm also deserves praise for its educational programs for the local community. Last season, farm staff worked with over 100 volunteers and educated over 2,280 children on sustainable farming, food sources, and plant biology at the farm. The farm also has a partnership with the New York City Department of Probation’s Youth WRAP Program, which serves young people on probation by providing life skills and job training.

According to a succinct history, which includes some photographs, on its website, Snug Harbor was founded in the early 19th century as a haven for aged, decrepit, and worn-out sailors by the will of Robert Richard Randall, the heir to a shipping fortune who died in 1801. It became a campus of 50 structures and 900 residents from every corner of the world, and by the early 20th century, was reputedly the richest charitable institution in the United States and a self-sustaining community with a farm, dairy, bakery, power plant, chapel, hospital, concert hall, dormitories, and a cemetery.

But the Randall endowment started to run out and the historic buildings began to deteriorate. New York City was persuaded by local activists and artists to purchase the property with the objective of transforming it into a cultural resource. The Heritage Farm is a very successful part of that 21st Century transformation.

(Frank W. Barrie, 5/23/18)

Mom’s Popovers: Brought Back to Mind By A Maine Soup Kitchen’s Awesome Community Building With Popovers Hot Out of the Oven

Easy to make popovers with a few basic ingredients: milk, flour, eggs, salt and some butter to melt at the bottom of the popover pan’s wells

Lofty and delicious popovers, with two wells left unfilled and the one in the center of the front row slightly less lofty since the well was only half-filled with batter instead of three-quarters filled

Indulging in big-time comfort food: flaky, eggy & tender popovers with a serving of flavorful bilberry fruit spread

In the current issue of Yankee Magazine, which for decades has been a welcome sight in the mailbox, a recipe for the summer specialty of popovers, at the non-profit Common Good Soup Kitchen in Southwest Harbor (a town on Mount Desert Island in Hancock County), Maine, was a reminder of my mom’s popovers cooked up once a year at Thanksgiving. I have held my mom’s memory close for more than 25 years, and on Thanksgiving Days in the past, I can recall her little bit of anxiety on timing the popovers to be hot out of the oven, just as the roast turkey was ready to be carved up for the annual feast. But I haven’t had a popover for decades, so the story in Yankee Magazine prompted some nostalgia for mom’s popovers.

Coastal Maine’s inspirational Common Good Soup Kitchen’s popovers, as described in Yankee Magazine, are hot and golden, with a perfect crunch on the outside, airy and tender on the inside- and even better with a dollop of house-made blueberry or strawberry jam. Mom’s were too and this recent Mother’s Day, this aging baby boomer decided to bake up some popovers.

And Common Good Soup Kitchen’s amazing all-volunteer staff, which bakes 400 to 500 popovers every day from mid-June through Columbus Day weekend for locals and summer people, is a story that deserves to be spread and perhaps become a model for other community soup kitchens. There are no prices set at the Maine soup kitchen, with customers invited to donate whatever they feel is appropriate.

So with the soup kitchen’s recipe in hand from Yankee Magazine as well as the popover recipe from the latest edition of Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker, and Ethan Becker (New York, NY: Scribner, 1997), an earlier edition of the cookbook was a favorite of dear mom, I decided to give it a try. I will confess, the first batch turned out like biscuits, not popovers, because I failed to use all purpose flour and in error used 100% pastry flour.

Brochures printed up by the National Co+Op Grocers, available at my hometown food co-op, Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY, include one on Flour. The descriptions provided under Types of wheat flours for all-purpose flour and whole wheat pastry flour provided the explanation why the first batch did not rise up into high, crusty, hollow beauties in Joy of Cooking’s terminology.

Pastry flour or soft whole wheat flour is milled from soft winter wheat berries, a different variety of wheat than the one used for bread baking. It has the ability to absorb more fat making it ideal for pastry and cake making. All-purpose flour is a blend of pastry flour and refined bread flour, and the bread flour which is ground from hard red spring or hard red winter wheat berries made all the difference in turning out high, crusty, hollow beauties the second time around.

Despite this culinary error, baking up a batch of popovers is extraordinarily easy with simple ingredients if you have a popover pan. And The Cook’s Resource, Different Drummer’s Kitchen in Albany, NY had the perfect popover pan, USA Pan’s (A Bundy Family Company) six Wells, Commercial Bakeware. With its deep, conical wells, this pan produced beauties, though the wells are so deep, the soup kitchen’s recipe for 6 popovers only filled 3 of the wells with the proper amount of batter, according to the Joy of Cooking’s recommendation of two-thirds to three-quarters full. The soup kitchen’s recipe recommended filling the wells one-half full, and also noted that a muffin tin is fine-the results are just a little less lofty. But I decided to stick with lofty, and I was able to fill three of the wells about three-quarters full of batter, and a fourth well, almost one-half full. All popped over the pan, but three were truly lofty, and all delicious: flaky, eggy and tender inside (big-time comfort food).

Common Good Soup Kitchen serves up its popovers with a dollop of house-made blueberry or strawberry jam. I used delicious bionaturæ organic Bilberry Fruit Spread. (Bilberry fruit, similar to blueberries and blackberries, has been considered multi-nutrient rich, and particularly useful for the maintenance of eye health.)

The recipe below tweaks Common Good Soup Kitchen’s with some additional tips from the Joy of Cooking’s recipe. I also used locally sourced ingredients as noted.

Ingredients

2/3 cup all-purpose flour [Farmer Ground organic whole wheat, all purpose flour from Trumansburg (Tompkins County), NY]

2/3 cup milk [Maple Hill Creamery’s plain kefir from 100% grass-fed cows kefir milk (adding a little savory tang) from Kinderhook (Columbia County), NY]

3 large eggs [Skyhill farm eggs from Seward (Schoharie County), NY, whose 300 hens of 26 heritage breeds are free to wander and fly unrestricted, except on coldest, windiest days]

1/4 tsp salt [freshly ground, with a mortar and pestle, Himalayan pink sea salt crystals]

1 and 1/2 tablespoons butter, cut into 4 thin slices [Kriemhild Meadow butter made with milk from the Hamilton (Madison County, NY) dairy farm’s grass-fed cows]

Preheat oven to 450 degrees.

Put popover pan in the oven while preparing the batter.

In a bowl, whisk together flour, milk, eggs and salt. (The recipe in Joy of Cooking specified only 2 eggs, but I used the extra egg and indulged in the eggier popovers.)

Remove the hot popover pan from the oven, and put a slice of butter into each well to melt. (I used only 4 of the pan’s 6 wells, so I put a sliver of butter in only 4 wells. Fill any unfilled cups one-third full with water so that the pan does not burn.

Divide the batter among the cups, filling them two-thirds to three-quarters of the way. (The soup kitchen’s recipe specifies filling the cups about halfway with batter, but I wanted loftier popovers and followed the Joy of Cooking direction, which resulted in two unfilled wells)

Bake for 15 minutes at 450 degrees, then reduce the heat to 350 degrees and bake for 20 minutes more until popovers are puffed and golden brown.

(Joy of Cooking notes: Do NOT open the oven to check the popovers until the last 5 minutes to avoid deflating them. I didn’t open the oven door until the baking time was complete. Instead, I turned on the oven light, and looked through the oven door’s glass window to gauge doneness and loftiness.)

The total baking time of 35 minutes specified above was just right: Perfect popovers.

(Frank W. Barrie, 5/17/18)

3 Cheers for Woodberry Kitchen’s Spike Gjerde & His Canned Maryland Tomatoes: Know Where Your Tomatoes Come From

Maryland tomatoes grown on small farms can now be processed/canned in Baltimore thanks to efforts by Spike Gjerde of Woodbury Kitchen

The Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY sells three brands of canned organic tomatoes: two from Italy, Jovial and Bionaturae and Muir Glen’s California tomatoes

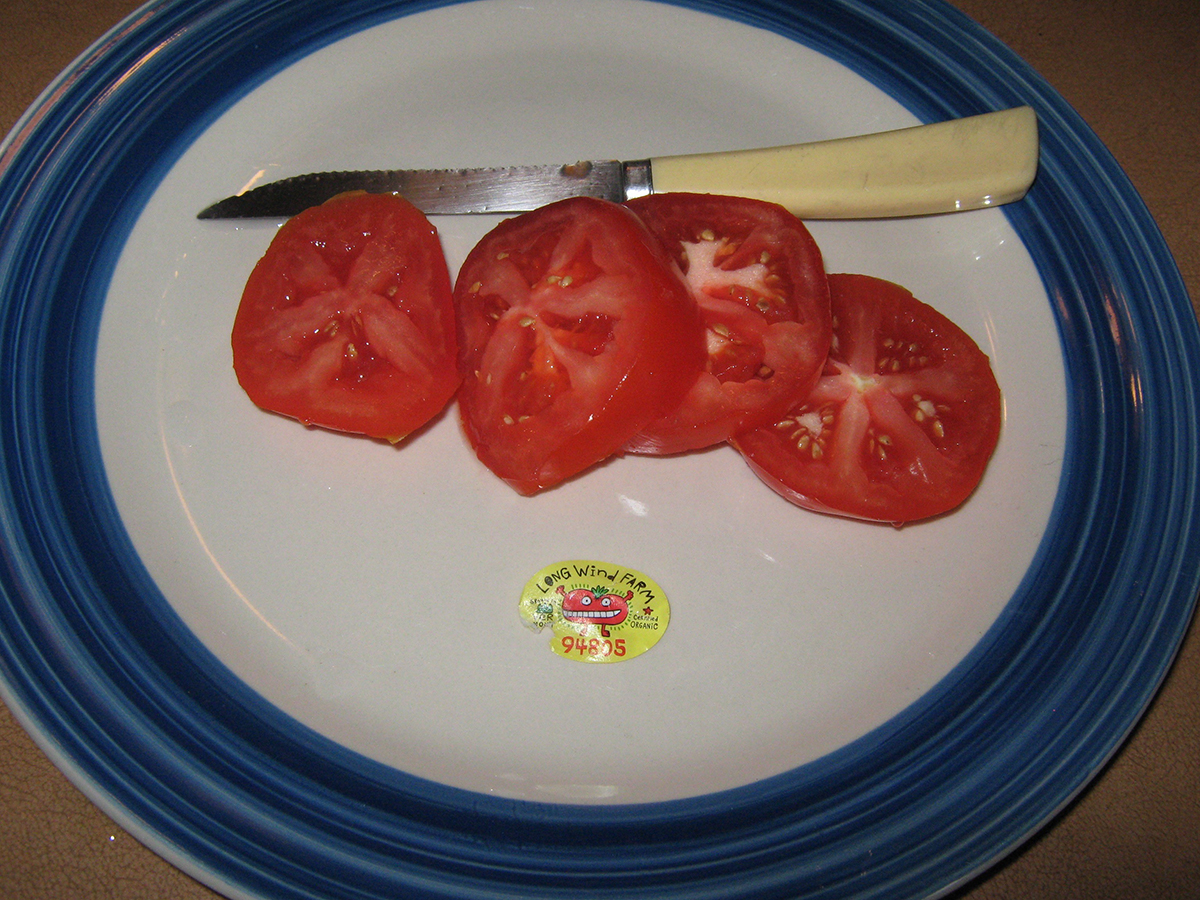

A fresh organic tomato in early spring, that tastes like a tomato should, and grown in soil (not hydroponically) from praiseworthy Long Wind Farm in Thetford, Vermont is a delicious (and nutritionally dense) treat

4 tomato seedlings get a head start on the growing season, with protection from cool nights and backyard ravenous squirrels, by use of Tomato Accelerator cages

The website for the farm to table restaurant Woodberry Kitchen in Baltimore, Maryland includes this impressive representation at its About Us tab:

All of the food on our menu was sourced directly from a local farmer or waterman. All of our spirits are from the US and their materials are thoughtfully sourced. All of our wines are organic, biodynamic or local, leaning towards the latter two. All of our beers are from farm breweries in Maryland.

This commitment to source food from growers of the Chesapeake for its menu has expanded with the growing success of the restaurant’s Woodberry Pantry, a Maryland State approved canning facility, which creates products with the same commitment, as the restaurant, to Maryland farmers. The Pantry operation now supports a whole local economy of tomato growing and processing/canning in Baltimore, Maryland. Kudos for Spike Gjerde and the effort to develop new revenue sources for, in his words, our farmers.

This consumer purchased on a recent visit to the Washington, DC area at Little Red Fox, a market and coffee shop (which serves up a delicious breakfast), a 20 oz. can of Spike’s Maryland Tomatoes which details these Farm Facts for the tomatoes in the can: Smithburg, Maryland’s Hawbaker Farm, Harvested September ’16; Yield: 240,000 lbs from 4 acres. Ingredients clearly noted: Plum Tomatoes, Salt. And these growing practices specified: no synthetic fertilizers, non-GMO seed, vine-ripened without ethylene glycol added. Plus, the can has non-BPA lining.

On return home to upstate New York, some googling around for information on Hawbaker Farm did not disclose to what extent, if any, pesticides might be used in growing tomatoes on this farm near Smithsburg, Md. in Waynesboro, Pa. Yet a can of tomatoes with a state’s name proudly worn on its label, which demonstrates support for local agriculture and a small farm, and not some distant corporation focused on ever-increasing profits, is so unusual and praiseworthy, no regret for my purchase of Spike’s Maryland Tomatoes.

But with tomatoes appearing #9 on The Dirty Dozen, the Environmental Working Group’s ranking of fruits and vegetables to avoid because of pesticide residue levels, this consumer is cautious when purchasing canned tomatoes, and fortunately, the Honest Weight Food Co-op in my hometown of Albany, NY offers canned organic tomatoes, albeit not canned Hudson Valley New York tomatoes, but certified organic, from afar: two brands of tomatoes from Italy, Bionaturae and Jovial, and Muir Glen’s from California. On its label, Bionaturae describes its tomatoes as grown on small family farms and naturally ripened in the Mediterranean sunshine. Jovial’s label notes its sweet & pure tomatoes are grown on small farms in Tuscany and packed on the very same day they are harvested. Muir Glen describes its tomatoes as grown on organic farms where they’re drenched in California sunshine.

In this era when it’s wise to be skeptical about food labels, are these 3 brands of canned organic tomatoes really grown in soil? Vegetables grown in rich soil, full of micronutrients and microbial life, are superior (there are some 1030 microbes on Earth – that’s a nonillion of them, and rich soil contains abundant microbial life, not so with hydroponic agricultural practices).

Bionaturae on its website notes that the sun, soil and tomato varieties provide the best tomatoes in the world. Jovial states on its website that our organic tomatoes are grown on just one organic, family farm in Italy, lovingly cared for during the hot summer months. No mention of soil but a review of the tab on Jovial’s website for Our Story and the concern for farming and tradition suggests that its tomatoes are rooted in rich soil. Muir Glen’s Field to Can in 8 hours slogan also suggest that its tomatoes are grown in soil and on its website where it describes Our Principles, the company emphasizes that Caring for the earth while growing great tomatoes is just part of what we do every day and illustrates these words with a farmer’s hand holding dirt.

Inspirational and perhaps even approaching a little bit of magic, is to savor a fresh and organic tomato in early spring (especially after an extremely long winter in upstate New York) from a farm in even a colder climate zone than the Hudson Valley of upstate New York, and located nearly 150 miles northeast of Albany. This fresh tomato was one of very few in number, perhaps a dozen, spotted in the produce department of the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany. Let us praise Long Wind Farm (certified organic) in Thetford (Orange County), Vermont. Located in the northern reaches of the Connecticut River Valley, Long Wind Farm emphasizes that its certified organic tomatoes are grown in Vermont soil and taste like a tomato should (but seldom do).

In this era of ungrounded and manipulative marketing claims, Long Wind Farm deserves credit and praise when it notes:

Our tomatoes taste so good because we select our varieties based on flavor rather than appearance. Then we grow them with tender love in rich soil (rather than the hydroponic way in a bag of coconut coir). The result is the best tomato you can buy.

Best tomato you can buy? I buy that claim. And the one tomato I savored in early spring cost $1.61, but worth every cent.

Most of the “organic” fresh tomatoes now sold in the supermarkets of the Northeast are actually hydroponically grown, usually in Mexico and Canada, with all of the tomato’s nutrition derived from a liquid feed, much like an IV tube, as noted by Long Wind Farm on its website. In fact, most of the world (including Canada and Mexico) doesn’t allow hydroponic produce to be certified as organic, but in our United States they can be certified organic, as a result of a recent vote of the National Organic Standards Board. (Members of the NOSB voted 8 to 7 to reject a proposal that would disallow hydroponic and aquaponic farms from being certified organic.) Now the Keep the Soil in Organic movement is focusing on determining next steps and discussion focuses on creating a different label: Some want an add-on label that would stand for real organic. Some want a stand-alone label that has nothing to do with the National Organic Program. Some want to pursue the Regenerative Organic Label that Rodale is promoting.

With tomato weather approaching, this backyard gardener has gotten an early start, setting out four organic tomato seedlings early in the growing season. The seedlings from Farm At Miller’s Crossing in Hudson (Columbia County, NY) are a range of varieties: Red Zebra (dark red fruit, gold streaked), Costoluto Genovese red paste type, Sun Gold cherry, and Lucky Tiger cherry, all for sale at the plant department of the Honest Weight Food Co-op. With nights still chilly, pop-up Tomato Accelerators (from Gardener’s Supply Company) get zipped up as the sun goes down in order to start the growing season early before hot tomato weather arrives.

Here’s to summer’s bounty and fresh, organic tomatoes grown in rich soil!

(Frank W. Barrie, 5/10/18)

How to Grow, Harvest & Cook Whole Grains: Clear Advice From An Expert

Sara Pitzer’s expert advice on how to Grow, Harvest & Cook Whole Grains in an updated edition, beautifully illustrated by Elayne Sears

With nearly 1,000 bins of bulk food, the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY offers all of the grains covered in the nine Chapter Headings of Sara Pitzer’s Homegrown Whole Grains: 1) barley, 2) buckwheat, 3) corn, 4) heirloom grains (amaranth, quinoa, spelt, emmer faro, einkorn), 5) millet, 6) oats, 7) rice, 8) rye and 9) wheat. And all are organic: Wow!

If you are an avid baker, wanting to take your bread baking to the next level or perhaps a locavore looking for the next food frontier in taste . . . or if you’re simply interested in learning more about the grains we take for granted, then Sara Pitzer’s Homegrown Whole Grains, Grow, Harvest & Cook Wheat, Barley, Oats, Rice, Corn & More (Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA, 2009) deserves a place in your library.

We don’t think twice about growing green beans, sweet corn or tomatoes in a vegetable garden. So why not wheat or rye or spelt?

While reading Amy Halloran’s The New Bread Basket, How the New Crop of Grain Growers, Plant Breeders, Millers, Maltsters, Bakers, Brewers, and Local Food Activists Are Redefining Our Daily Loaf for purposes of a book review on this website, I became curious about growing grains in my backyard garden in rural Albany County in upstate New York. After all, upstate New York was the breadbasket of America until the Erie Canal in the early 19th century opened up the vast and fertile Midwest to cultivation. In our time, the fertile midwest has become the locus for the industrial-sized, mono crop growing of commodity wheat, corn and soy, with the main focus on economics and profits overwhelming concerns for taste, freshness, and bio-diversity.

In Sara Pitzer’s introduction to Homegrown Whole Grains (which is actually a new, updated edition of her Whole Grains, Grow, Harvest & Cook Your Own, written nearly thirty years ago and published by Garden Way, Inc. in 1981), she explains that the first version was written during the back-to-the-land era when “hippie food” was long on nutrition and short on taste. This new, updated edition was written for a new generation of local food enthusiasts. It is a concise manual for growing, harvesting, and cooking homegrown grains.

Organized by type of grain, Pitzer outlines seed sources, culture requirements, possible pests and diseases, best ways to process the harvest, and a collection of kitchen-tested recipes. Her descriptions and yield expectations are based on a modest-size plot of 100 square feet, right-sized for many backyards. She cautions that while growing grain is fairly easy, threshing, winnowing, and hulling take lots of energy, verging on brute force.

Some gardeners may prefer to plant grains as cover crops, or simply to buy unprocessed organic grains in the bulk department of a local food co-op. Wherever you enter the process, Pitzer has clear, practical advice and sources for buying, storing, grinding, and cooking a wide variety of grains: barley, buckwheat, corn, amaranth, quinoa, spelt, emmer farro, einkorn, millet, oats, rice, rye, or wheat. Between each well-organized grain section are inspirational profiles of grain “enthusiasts” from around the country.

The final Resources section includes sources for seeds, hand mills, advocacy groups, and more books. Though I probably won’t be growing grains in my backyard any time soon, I do plan to keep Homegrown Whole Grains on my cookbook shelf for its simple and clear recipes and nutritional information.

A perfect companion to The New Bread Basket, Sara Pitzer deserves much credit for providing guidance in Homegrown Whole Grains on what to do with all those mystery grains in the bulk food department of a food co-op, like that of the remarkable Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY, with its nearly 1,000 bins of bulk food.

(Laura Shore, 5/1/18)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): Coincidentally, the current issue of New York Archives magazine (Spring 2018) includes an article by Amy Halloran, whose The New Bread Basket is spotlighted above, on how the Erie Canal “changed patterns of farming and milling in early America.” In her well-researched article for the magazine, Daily Bread, The Erie Canal Forged A Path For Amber Waves Of Grain, on New York’s history of grains, Halloran noted that the Erie Canal “set the stage for a centralized food system and industrial scale agriculture.” Referencing Andrew F. Smith’s Eating History: Thirty Turning Points in the Making of American Cuisine (Columbia University Press, New York, 2009), Halloran pointed cogently to the moment when she was able to wrap her head around the realization that the efficacy of the transportation grid, starting with the Erie Canal in the early 19th century, cast aside the idea that food had to be purchased from nearby farms or farmers markets. The habit of buying locally was replaced early-on in American food history by a mandate of buying cheaply from afar.]