Archive for October 2016

Freaks, Radicals and Hippies: Counterculture in 1970s Vermont

PEACE Hand Puppet from Vermont’s Bread & Puppet Theater

NOFA (Natural Organic Farmers Association) established in the 1970s in Vermont to share organic farming practices

Many books & posters from the era on display including Helen & Scott Nearing’s Living the Good Life

Hippie Scare front page story in “The Only Daily Newspaper in the World That Gives a Darn About St. Albans & Franklin Counties

Vermont Historical Society’s current exhibit, Freaks, Radicals and Hippies: Counterculture in 1970s Vermont, suggests that the American local and organic food movement, now so vital across the United States and Canada, had its beginnings, in some good measure, in the back-to-the-land movement, which was a big part of the counterculture in 1970s Vermont. This fascinating exhibit, which opened in late September 2016, will be on display for nearly a year, until September 2017, at the Society’s Vermont Heritage Galleries at the Vermont History Center in the historic Spaulding school building in Barre (Washington County) less than 10 miles from Vermont’s capital city, Montpelier (Washington County).

For the past two years, the Vermont Historical Society has collected objects, documents and memories from the “tumultuous” 1970s in Vermont when many young people, arriving in the state in the late 1960s and 1970s, were “rebelling against the established order.” Anti-Vietnam War sentiment bolstered the rejection of “the system” and propelled a movement back-to-the-land. In the succinct words of Stephen Perkins, Executive Director of the Society: “Three-years-in-the-making, this exhibit and attendant programming brings together research, first-person interviews, material culture, and the indescribable ethos of the time (emphasis added).”

In preparation for the special exhibit, a “counterculture archive” has been created by the Society which will be preserved. Curator Jackie Calder notes that the oral histories, artwork, objects, photographs and documents will become a part of the Vermont Historical Society’s permanent collection and will be accessible to researchers. Over 50 oral history interviews were collected in 2015 and 2016, and are available on-line as part of the Vermont Historical Society’s Digital Vermont project.

A strong case is made that the 1970s in Vermont “was a crucial turning point for food and agriculture in Vermont” and the start of the nationwide movement for “real food” based on organic agriculture, heirloom seeds, locally sourced produce, food buyers’ cooperatives and farmers’ markets. In the Society’s newsletter, History Connections (Summer 2016), it’s noted that “if one single unifying theme could connect the entirety of the counterculture experience in 1970s Vermont, it would be food (emphasis added).”

Still, the three huge objects of “material culture” on display, which grab the visitor’s eye, are not actually food related. On the sloping grounds outside the Vermont History Center’s Spaulding school building is a colorfully painted old Volkswagen bus. You immediately know you’ve come to the right place for an exhibit focused on the 1970s Vermont counterculture.

Inside the entry way, is an extraordinary Peace Hand Puppet from Vermont’s Bread & Puppet Theater. Founded in 1963 on New York City’s Lower Eastside, in 1974 Bread and Puppet moved to a farm in Glover (Orleans County) in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont.

And inside the actual exhibit in the Heritage Galleries is half of a geodesic dome, striking to this visitor who has been intrigued of late by the remarkable Growing Spaces® Growing Dome similarly shaped. It’s a shape that is said to be “the strongest structure in the world” according to information on Growing Spaces website. Udgar Parsons, founder of Growing Spaces, based in Pagosa Springs (Archuleta County), Colorado, in words that echo 1970s Vermont counterculture, notes that his small company’s geodesic dome greenhouse kits “demonstrate a solar self-sufficiency that keeps fresh food on the table, even within the challenge of environmental and economic changes.” It might now be said that the geodesic dome has become “food” related in 21st America with Growing Spaces’ greenhouse kits.

The main exhibit area includes video and listening stations which “showcase” stories and images from the era. This visitor enjoyed particularly the stories and “oral histories” at the video and listening station for Food: Access, Health, Security.

Ginny Callan, a student at Goddard College from 1970 to 1974, recounts the founding and running of the Horn of the Moon restaurant in Montpelier (perhaps one of the first farm to table restaurants in the state) and a “cross-cultural meeting ground,” offering local and organic food to Goddard students as well as UPS drivers. An “At The Nation’s Table” restaurant review by Marialisa Calta from 1988 in the New York Times included this telling description of the restaurant’s continuing commitment to political activism a few years into its operation:

One counter holds pamphlets, petitions and leaflets left by patrons. Recently it held a flier calling for the boycott of Chilean wine and fruit; an exceptionally polite petition asking the United States Government to ‘encourage the Chinese Government to stop their human-rights violations in Tibet,’ and campaign literature for Mayor Bernie Sanders of Burlington, Vt., a Socialist candidate for Congress. There was a collection box inscribed with the phrase ‘a quarter a day to keep the Contras away.

Ms. Callan sold the Horn of the Moon restaurant in 1990 and it closed its doors a few years later according to an article by Dot Helling in The Bridge, Montpelier’s independent and local newspaper. Yet as of the date of this post, the Horn of the Moon Restaurant Cookbook is still available on Amazon, a new copy for over $50.00 but some used copies are reasonably priced.

Other stories to hear at the listening station on food related subject matter include Diane Gabriel’s emblematic account on how she moved in 1969, when she was 22, from a Bronx neighborhood near Yankee Stadium to Fayston (Washington County), Vermont. In Fayston, she became interested in new ways of growing and preparing food, including the use of cold frames, canning, drying apples, and cold storage of root crops. Home-made granola and grinding wheat berries to make bread became part of daily life.

Stories are also told on how food buying groups evolved into food co-ops. Onion River Co-op in Burlington (now City Market/Onion River Co-op) was started up first by Larry Kupferman and Susan Schoenfeld as a food buying group. Plainfield Co-op was propelled into existence by Goddard College students. And the history behind the establishment of NOFA (known as the Natural Organic Farmers Association back in the 1970s, and now as the Northeast Organic Farming Association with state chapters today in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont) is fascinating. According to Bob Light, who was involved at the start, the lack of farming knowledge was a challenge in determining ways to grow vegetables organically and to deal with insects and weeds without the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers.

Time is also well-spent hearing the stories related at the listening station for Living Collectively: Founding and Philosophy. The exact number of communes in Vermont during the era “may never be known” since they often didn’t last longer than a few months or years. At most, it is estimated that there may have been as many as 100 communes or collectives, with a year-round population during the early 1970s of up to a few thousand people. Rock Bottom Farm: Study of a Commune, a 32-minute film by Thomas Lane and Gary Osmond from 1972, courtesy of the Dartmouth College Archives, tells the story of a commune started by Woody Ransom in South Strafford (Orange County) Vermont which had pigs, cows, sheep and chickens in addition to growing vegetables.

In its recent newsletter describing the exhibit, the tension between traditional Vermonters, with deeper roots in the state, and the late 1960s and 1970s newcomers is pungently described:

Many people believe that the influx of new people ruined the state forever. Others believe that the state was saved by these newcomers, who brought invigorating ideas, politics, and social mores to a state that had been in serious decline.

The many Vermont listings on this website for CSA (community supported agriculture) farms, cheesemakers, farmers markets, farm to table restaurants, craft bakeries, etcetera, lends support to the more generous view of the “others” noted above. The numbers are stunning: our directories for Vermont include information on 60 CSAs, 41 cheesemakers, over 60 farmers markets, over 60 farm to table restaurants and six craft bakeries using local grains milled into flour. And this explosion of environmentally and socially conscious enterprises are all rooted in the second least populous of the U.S. states, the Green Mountain state of Vermont with its 626,562 inhabitants at latest count.

This inspiring local and organic food culture can be a model for citizens of other states to embrace. In the vanguard in the transformation of the way Americans (who care about their health, environment and local economies) produce, buy and consume their food, Vermont has bushwhacked a path away from the industrial/commodity agriculture system and provides hope for an American agricultural future that sustains the health of people, communities and the environment.

Kudos and gratitude to the Vermont Historical Society for its recognition and preservation of the memories of the back-to-the-land-movement in Vermont of the 1970s and the mounting of its fascinating exhibit.

[Freaks, Radicals and Hippies: Counterculture in 1970s Vermont, Monday-Friday 9AM to 4PM (Open until November 2017), Vermont Heritage Galleries at the Vermont History Center, 60 Washington Street, Barre (Washington County), Vermont]

(Frank W. Barrie 10/26/16)

Delicious Breakfast Wraps In The American Heartland: Lincoln, Nebraska

Maggie’s Nut Meat Tacos, made with farmstead cheddar, tomatoes, onions and topped with an avocado cream sauce & served with a delicious green salad

On a cross-country trip from Vermont to Oregon, friends invited us to break up the trip midway with a stopover at their home in Lincoln, Nebraska. Our friends, who belong to a local CSA farm and love good food (and even have a clay oven to prepare delicious meals), knew that breakfast or lunch at Maggie’s Cafe would fit our desire to experience the local, good food movement.

Maggie’s Café is also known in Lincoln as Maggie’s Vegetarian Café (AND Maggie’s L.O.V.E. for Local, Organic, Vegetarian, Ethical). Our friends’ enthusiasm for Maggie’s was well-placed, and our delicious meal at this Nebraska café was clear evidence that farm-to-table dining options have taken root, not only in the green republic of Vermont and in Portland, Oregon, but in the American heartland.

In fact, our expectations were met with what may be the best breakfast wrap in Nebraska especially for those of us who care about where our food comes from and how it’s produced. The deliciousness of ultra-fresh local ingredients was manifested in this outstanding vegetarian café’s offerings.

A brick-faced store front which is eclectically decorated and cozy, Maggie’s reminded me of a food stall at Philadelphia’s famous Reading Terminal Market. In business for 16 years, Maggie’s is no newcomer to satisfying the public palate.

The café offers more than a half dozen different wraps, which are prepared with 12″ flour tortillas (for an additional $1.00, whole wheat is available). We opted for the Three Cheese Melt wrap which combines Jisa Farmstead cheddar, provolone and mozzarella cheeses, roasted sunflower seeds, Shadow Book Farms mixed greens, spinach, garden tomatoes, and roasted red pepper dressing. A smear of dressing and a sprinkle of parmesan adorned it, setting the mouth to water just from the pretty picture before the scents of bubbling cheese, fresh greens and tomatoes even hit my nose.

We also shared Maggie’s Nut Meat Tacos made with Jisa Farmstead cheddar, tomatoes, onions and dolloped with avocado cream sauce. The tacos were accompanied by a beautiful fresh salad with Shadow Brook Farms greens, carrots and cucumber. Often prepared with ground and seasoned walnuts, the delicious nut meat tacos on the day we ate at Maggie’s were made with ground pecans.

Other menu options included a Free Range Frittata, Southwest Black Bean Casserole, and Roasted Veggie Pizza. And the café’s 2012 Food Network Magazine award winning Avocado Melt Wrap is a favorite of customers.

According to the café’s website, Maggie “is one of the founding members of Slowfood Nebraska” and has attended the Terra Madre conference in Turin, Italy as a delegate of Nebraska. The café notes its “pride” in working with local farmers and organizations which support sustainable agriculture. With impressive plating and ultra-fresh flavors, Maggie’s delivers a taste of the Slow Food vision in the heart of America.

And the café deserves praise for its ever-growing network of local food businesses and farmers that work to support one another. Maggie’s sources ingredients from many local producers by utilizing Lone Tree Foods (an innovative food distributor which connects its members, who are “sustainable farmers”- well defined on its website, with buyers, particularly in Lincoln, as well as Omaha, the largest city in Nebraska, and Council Bluffs in Iowa), Robinette Farms (for eggs), Le Quartier Baking Company (for pizza crusts), Wise Oven Bakery (for sourdough breads), and Marlene Tortilleria (for corn tortillas), in addition to Jisa Farmstead and Shadow Brooks Farm noted above.

It’s easy to understand how these relationships are flourishing in Lincoln: when I inquired of the manager about their food sources he was open and forthcoming, with an enthusiasm to chat with me about them. Our tastebuds, to use the words from Maggie’s website, indeed, did “appreciate the freshness of the harvest sourced from Nebraska family farms.” [Maggie’s, 311 North 8th Street, 402.477.3959, Breakfast & Lunch: Mon-Sat 8:00AM-3:00PM, Sun 11:00AM-3:00PM www.maggiesvegetarian.com]

(Lucas Knapp 10/21/16)

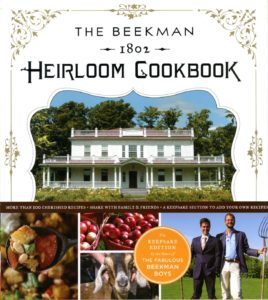

Seasonal Recipes from the Beekman Boys: The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Cookbook

It’s not surprising that a cookbook from the Beekman Boys would be a classy, useful tome: everything they present they present with commendable style. The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Cookbook (Sterling Epicure, New York, NY 2011) collects over a hundred recipes, nicely described and beautifully photographed by Paulette Taormina arranged by season and encouraging you to make the most of what’s available nearby. (Photographer Taormina is a fine art photographer known for her series, Natura Morta, which features imagery inspired by 17th century old master still life painters.)

Brent Ridge and Josh Kilmer-Purcell fled (more or less) the wilds of Manhattan to live in the wilds of rural Sharon Springs, NY, on a two-centuries-old farm where they quickly began raising goats and tomatoes, an effort chronicled in a television series that helped establish their renown. Kilmer-Purcell has written best-selling memoirs; husband Ridge is a physician who spent a few years as Vice President for Healthy Living for Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia. It’s no surprise that their Beekman 1802 brand has become synonymous with good taste. And the food products taste good. Quite good.

Fall recipes: Havest Beef Chili With Pumpkin & Beans, Leek & Potato Gratin, Butter Crumb Cauliflower, and Macaroni & Cheese with Mushrooms & Kale

Can you achieve a similar result with their recipes? The book, co-written with Sandy Gluck (former food editor for Martha Stewart’s Everyday Food magazine), is quartered into seasons, with each season further divided into courses. Spring’s starters, for example, include a dandelion salad and asparagus torte, with a main dish of lamb burgers with cucumber-yogurt sauce. There’s a starter of a cucumber cooler for summer, whose main dishes include stuffed peppers with fresh corn and a grilled summer squash pizza. And jumble berry pie (with blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries) for dessert.

But with fall upon us, I turned to the section of the book that’s color-coded orange and selected a main dish of Harvest Beef Chili with Pumpkin and Beans. I’m fortunate enough not only to live on a farm that produces almost the entirety of my produce for summer and fall, but also to have farms nearby from which I can source other ingredients. Thus I visited Windrake Farm to secure a cut of beef, a four-pound round marbled with the yellow fat characteristic of a Jersey cow.

The recipe warns you away from round, preferring the more-marbled and therefore more-tender chuck, but I wasn’t too worried: I could afford a little extra oven time. The pumpkin, onion, garlic, and bell peppers came from my own gardens. Because I had more than twice the beef the recipe called for, I more than doubled the recipe. This earns me significant points from my wife, who needs lunches for workdays.

Flour-dredged beef chunks are browned in and removed from a Dutch oven, the onions, peppers, and garlic gets a sautée, then a sauce is developed. The recipe suggests adding water, but I substituted a bottle of Saranac Ale for some of it. With no ancho chili powder on hand, I substituted a little smoked paprika; otherwise, I followed the recipe’s plan of coriander, cumin, and cocoa powder, the last-named a nice touch.

With the meat returned to the pot and chunks of raw pumpkin added, it’s supposed to cook in a 350-degree oven for an hour and a half. My round needed an extra 45 minutes to get tender. Canned pinto beans are added shortly before the finish. The verdict: a keeper. We’ll try it next time with beef chuck to compare.

A dish like this begs for potatoes, and there’s a side-dish recipe for Leek and Potato Gratin just a few pages away. With a bounteous late crop of leeks and some potatoes still waiting in cellar storage, I increased the recipe enough to move it from a ten-inch to a twelve-inch cast-iron skillet. It’s the first recipe I’ve seen for this dish that doesn’t call for cheese, which seems heretical, but I tried it this way, using only cream and half-again as much milk for its sauce.

Two layers of par-boiled potatoes are laid out in the skillet with layer of well-sautéed (and well-washed) leeks and garlic between, and it’s baked until potato edges start to brown, which took nearly an hour. Again, a winner – and the leftovers vanished almost instantly.

I’ve shared two of the more complicated recipes in the book; you’ll find far fewer steps to follow in much of the rest, and the side-dish of Butter-Crumbed Cauliflower I prepared to accompany this dinner was startlingly simple. I cut my last-remaining head of cauliflower into florets, steamed them until tender, then tossed them in a sautée pan of butter with a sprinkle of nutmeg. The recipe calls for panko; I used regular bread crumbs. The point is to add a butter flavor to the crunch, and this it did. Cauliflower doesn’t need much more, but if you’re adventurous, add chopped hard-boiled egg to the mixture and you have a classic Polonaise.

There’s usually some leeway when straying from a recipe, but not in baking. It was my fault for making a poor assumption. I assumed that the yeast in my fridge was too old and the amount should be increased. Also, I took the lazy way out and used a bread machine, which may have inflicted its own vagaries upon the process. At any event, my loaf of Pumpkin Cheese Bread went nuts, bursting its middle and cascading down the sides of the pan. It still tasted fantastic, the mixture of puréed pumpkin and lots of cheddar cheese giving it an autumnal flavor and a texture that reminded me of Yorkshire pudding. We’ll try it again soon with the correct amount of yeast.

Finally, a dish borrowed from the book’s winter pages, but one that gave us a chance to use up some kale by putting it in a casserole with macaroni and cheese.

I have to confess that, out of pure snobbery, I’ve never before made any version of macaroni and cheese. It seems a silly enough dish that not even a heap of kale ought to be able to ruin it. Which it didn’t, at least not quite, but kale has such a distinctive characteristic of its own that it never seemed to mix with the rest of dish. You’d get a big spoonful of macaroni and cheese. With some intrusive fronds of that green stuff. The Beekman Boys’ Macaroni and Cheese with Mushrooms and Kale recipe fills it out with mushrooms, calling for the porcini and cremini varieties, but my local supermarket finds it challenging enough to carry portobellos. At any rate, I went for the cheaper white mushrooms, and sautéed them separately with butter and lemon juice before mixing them into the dish. Good thing I have smoked paprika on hand, because in this recipe it’s actually called for. Once again I used regular old bread crumbs instead of panko, but I think the result more than suited the recipe’s premise.

Clearly, there’s a long way to go before I make any kind of dent in this book, but each of the dishes I prepared came out nicely enough to encourage me to look ahead. We have a long, cold winter threatened, so a dish of Pasta with Cabbage, Bacon, and Chestnuts not only will add inner warmth but also get rid of some of our overabundance of cabbage. And I’m also anticipating meals of Pork Roast with Root Vegetables, of Bourbon Roast Turkey with Cornbread Stuffing, and, for dessert, the cream cheese-frosted Spiced Carrot Cake.

There’s a succinct, effective narrative to each of the recipes, and many sidebars that tie in with what you’re preparing. Alongside the many finished-product photos are views of the farm, giving a good sense of moving through the seasons as you page through the book. All of which makes this cookbook not only a great keepsake, but an excellent, year-round appropriate gift.

(B. A. Nilsson, 10/12/16)

[Editor’s Note: The Beekman Boys were on hand to sign The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Cookbook at the Forever Farmland supper held this past summer at Hand Melon Farm in upstate New York’s Washington County. This supper prepared by the Chefs Consortium was a fundraiser for the Agricultural Stewardship Association, which preserves farmland in upstate New York’s Rensselaer and Washington Counties). Given B.A. Nilsson’s thumbs-up review of the Beekman 1802 Heirloom Cookbook, we will be sure to check out the Beekman Boys’ two subsequent cookbooks: The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Vegetable Cookbook (Rodale, New York, NY 2014) and The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Dessert Cookbook (Rodale, New York, NY 2013). (FWB)]

Who Eviscerates The Turkeys Processed For The American Plate?

Dozens of men from Texas, with intellectual disabilities (guys with IQs of 60 and 70 in the words of their employer), wound up living for 30 plus years in virtual servitude in the small Iowa town of Atalissa (Muscatine County). They were there, a thousand miles from Texas, in order to provide grossly underpaid labor to a turkey processing plant in the nearby and larger Iowa town of West Liberty (a word that is mightily ironic in this instance). Dan Barry in The Boys in the Bunkhouse, Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland (HarperCollins, New York, NY, 2016) tells a riveting story of these men, called “boys” by nearly everyone in their hard-working lives, in his non-fiction account of rescue and resilience. His powerful and emotional narrative isn’t simply focused on allocating blame but rises to an inspiriting level by finding the light in a tale of much darkness.

Dozens of men from Texas, with intellectual disabilities (guys with IQs of 60 and 70 in the words of their employer), wound up living for 30 plus years in virtual servitude in the small Iowa town of Atalissa (Muscatine County). They were there, a thousand miles from Texas, in order to provide grossly underpaid labor to a turkey processing plant in the nearby and larger Iowa town of West Liberty (a word that is mightily ironic in this instance). Dan Barry in The Boys in the Bunkhouse, Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland (HarperCollins, New York, NY, 2016) tells a riveting story of these men, called “boys” by nearly everyone in their hard-working lives, in his non-fiction account of rescue and resilience. His powerful and emotional narrative isn’t simply focused on allocating blame but rises to an inspiriting level by finding the light in a tale of much darkness.

The ghastly exploitation of the labor of “the boys in the bunkhouse” began with arguably good intentions to give purpose to the lives of the intellectually disabled, who were mostly institutionalized in Texas state schools in the early 1970s. In Barry’s words, the boys “wanted liberation from state school life.”

Hill Country Farm, Thurman Harley (TH) Johnson’s turkey ranch in Goldthwaite (Mills County) in east Texas, raised thousands of turkey hens. When they grew to be about thirty pounds in about 28 weeks, they were ready for artificial insemination because the top heavy turkey toms would damage the turkey hens during mating and were “not as efficient delivering semen.” In eye-opening detail, Barry describes the laborious procedure from milking the ranch’s toms, “with syringes filling up with semen and ‘extenders,’ a combination of saline solution and nutrients” to the insemination of the hens. The turkey ranch would become successful in training the men from the state schools to expertly assist in this task: “They caught these birds. They milked the ornery toms. They held down the terrified hens.”

The labor of the men from the state schools was especially appreciated as a result of the termination of “a mostly forgotten government arrangement that allowed countless Mexicans to cross the border to work on American farms and ranches” known as the bracero program. The program had been regulated to some degree: “The Mexican guest workers could be hired only during a labor shortage; they could not be used to break strikes; and they had to be provided with decent food and housing, as well as free transportation to the border when their contracts lapsed.” But the program “more than fulfilled its great potential for abuse,” and Barry notes that the former US Department of Labor official who oversaw the program would call it “legalized slavery” explaining its termination in 1964.

In the 1970s, Barry writes that the turkey market was shifting away from east Texas, and TH Johnson and Kenneth Henry decided “the time had come to send the boys of Henry’s Turkey Service out into the wider world, beyond the Texas border.” They had been trained to be “turkey-savvy laborers” at Hill Country Farm and now could be contracted out “to do those high-turnover jobs no one else wanted to do, because the work was hard and low-paying and repetitive, a bloody, filthy, feathery mess.”

Henry’s Turkey Service had its employees “work turkey” in Missouri, Illinois, South Carolina and Iowa, and Barry tells the story of the 31 Henry “boys” who worked in the West Liberty, Iowa turkey processing plant and lived in the “bunkhouse” in Atalissa (whose welcoming sign on the road into the small Iowa town noted “POP. 271 & 2 GRUMPS“).

Dan Barry is a master observer of details and his description of the evisceration process for a turkey on the industrial-style assembly line worked by the “boys” in West Liberty is explicit, and to a reader who is unaware of what goes into “processing” the various turkey products sold in a conventional American supermarket- likely shocking. Barry writes:

As each truck pulls to a stop in the bay, some of the men . . .reach into the crate, grab the forty-pound toms by the legs, and hang them by their feet on V-shaped metal shackles that dangle along an overhead conveyor. . . they fight back with their surprisingly powerful wings. The trick is to grab a foot with one hand, swing that plump body almost behind you, grab the other foot, and hook it.

The conveyor carries the shackled turkey inside the plant to be stunned in a shallow pool of electrically charged water, after which a device slits their throats to make them ‘bleed out.’ The carcasses are then immersed into a vat of scalding water, so hot that fans are needed to at least stir the humid air, and then pass through a series of mechanized rubber fingers to beat away the feathers. A worker called a ‘cutter’ removes the hocks [two hind legs], while others, called ‘pinners,’ pluck away any stubborn feathers.

The birds, fat and pink, plop onto tables, and the evisceration begins. Workers called ‘rehangers’ attach the carcasses by the legs to the shackles of a second conveyor-a critical moment in the process, dictating the pace of the assembly line. A missed shackle means idle moments, lost revenue.

Next in line, the ‘three-pointers.’ These workers grab the tail with one hand, the neck with the other, and put the head in the V of the shackle. Then a cutter slices a hole under the breast.

Once cut, the shackled turkey moves on to the ‘drawers,’ who reach into the carcass to pull down the viscera-the heart, intestines, liver, gizzard, and spleen . . .

A worker with the evocative job title of ‘heart cutter’ grabs the heart, still attached to the viscera, and cuts away the organ and the valve stem with air scissors. The heart is then sent down a pipe to join its visceral mates in the ‘giblet cooler,’ while the valve is thrown in the ‘river,’ the water-fed trough that carries away the offal.

The turkey then swings to the ‘croppers,’ who remove the bird’s feed-filled digestive system. . .

There was a trick to pulling crop- or pulling guts, as it was sometimes called. [One of the boys who became an expert in this task, Henry Wilkins, explains] ‘Take this finger up there, pull the skin apart, take both your fingers up there, pull it straight down. The crop’s out and you throw it in the trough.’ (pp. 88-89).

When Dan Barry saw the news reports in the spring of 2013 about the landmark $240 million judgment for 32 former employees of Henry’s Turkey Service, awarding each of them $7.5 million for emotional harm and punitive damages, he knew he had an extraordinary story to investigate and tell. (The award was the largest in the history of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.) No surprise then, that Boys In The Bunkhouse climaxes with a riveting retelling of the trial and the pursuit of justice by government attorney Robert Canino, who invested his body and soul in the litigation.

But Dan Barry does not end his story there. Rather, two of the social workers involved in aiding the men who had worked in the turkey processing plant in Iowa realize that a brother of Carl Wayne Jones, one of the rescued Iowa “boys,” was “still working turkey” at a plant in Newberry, South Carolina. Barry continues his narrative and follows the social workers to “a collosal gray-concrete meatpacking plant operated by Kraft Foods, the owner of the Rich brand.” Through the efforts of the two social workers and the assistance of white hat EEOC lawyer Robert Canino, Leon Jones (the brother of the already rescued Carl Wayne Jones) is removed from the South Carolina “bunkhouse” by county and state officials of that southern state and provided with “proper housing and services,” along with the opening of “several investigations.”

Still, is the story truly over? Out of the corner of his eye, Barry observed “a young man sprawled on a Barcalounger and watching a Spanish-language television program at high volume (emphasis added).” This small detail caught this reader’s attention and brought to mind Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation, the bestseller that was made into a film by Richard Linklater which shined a light on the exploited immigrant labor in the meat packing industry.

In this reviewer’s opinion, the story is never ending and it is fair to place some responsibility on the consumer to know where their food is coming from and how it is being produced. No simple task, but there is one particular way that it can be more easily accomplished: participation as a shareholder in a community supported agriculture (CSA) farm.

It’s with some sense of relief to end this review by noting that the “good food movement” has reached into the small town of Atalissa, Iowa. The Tygrett family’s Oakhill Acres CSA farm is a source for certified organic produce, small grains, herbs, honey and eggs (and is included in this website’s directory of Iowa CSA farms). Atalissans and others in the eastern Iowa county of Muscatine can choose to know where their food comes from and the labor that went into producing it. (And for a turkey this Thanksgiving holiday, Eatwild’s directory of 1,400 pasture-based farms is an excellent resource.)

(Frank W. Barrie 10/1/16)