Archive for April 2016

Rotate Your Baby’s Food, Just Like Your Puppy’s

Baby Food aisle at the Honest Weight Food Co-op: store’s food policy considers “moral & ethical production, environmental stewardship, healthy living & safety”

Baby food for sale at Honest Weight: Earth’s Best baby food in jars & its whole grain rice cereal and oatmeal cereal & Little Duck Organics’ Mighty Oats Cereals

In Pukka’s Promise, The Quest for Longer-Lived Dogs, (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, NY 2013), Ted Kerasote’s decision to feed his puppy Pukka an AAFCO-certified raw food diet has one major caveat. In his wonderful, memoir-like guide to caring for a dog to ensure a long life, he describes testing commercial kibbles, as well as commercially available raw-food diets (frozen and dried ones) for lead, and found no detectable level of lead in only three. His concern about heavy metals in foods for dogs, confirmed by this testing, reinforced the wisdom of what Dr. Joe Bartges, on the faculty of The College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Tennessee, told Kerasote: to rotate a dog’s food so as “minimize the risk of feeding the same heavy metals year after year.”

This wisdom also applies to humans and especially babies. Like puppies, the body weight of babies increases substantially over time, and the effect of heavy metals on a small baby is disproportionally greater than on weightier adults.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently acted on this concern. Along with its recent proposal to set limits for inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal of 100 parts per billion, the FDA has “urged parents to vary the kinds of iron-fortified cereal they feed their babies by using those made of oat, barley and multigrain” according to an article, F.D.A. Offers Arsenic Limit In Rice Cereal For Babies by Catherine Saint Louis in the New York Times (4/2/16). In support of its action, the FDA emphasized that “national intake data show that people consume the most rice (relative to their weight) at approximately 8 months of age.”

According to reporter Saint Louis, the FDA tested 76 rice cereals for infants “and found that about half had more inorganic arsenic than the proposed limit.” She notes that the FDA’s limit of 100 parts per billion earned the approval of Keeve Nachman, a professor of environmental health sciences at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who studies arsenic in food. According to Prof. Nachman, “having a line in the sand where there wasn’t one before at least gives companies something to work with.”

In addition, FDA officials recommended that pregnant women also vary the grains they consume. As rice plants grow, they absorb more arsenic than other crops. According to Plant Biologist Jody Banks of Purdue University quoted in Deborah Blum’s The Trouble With Rice (NY Times, 4/18/14), “The issue with the rice plant is that it tends to store the arsenic in the grain, rather than in the leaves or elsewhere.” In its press release, the FDA noted that although arsenic occurs naturally in soil and water, fertilizers and pesticides also contribute to arsenic levels.

In its “Advice for Consumers,” included in the FDA press release, like Dr. Joe Bartges’ recommendation to Ted Kerasote on his dog’s diet, the federal agency advises “all consumers to eat a well-balanced diet for good nutrition and to minimize potential adverse consequences from consuming an excess of any one food.” In sum, rice cereal shouldn’t be the only source, and does not need to be the first source, of nutrients for your baby.

The website Momtastic Wholesome Baby Food offers “easy, fresh & nutritious homemade baby cereal recipes” using whole grains, including a rice cereal made from brown rice. In making the various baby cereal recipes, the whole grains are first ground (in a blender or food processor) into a powder. It would be advisable to use organic whole grains since as noted by the FDA, fertilizers and pesticides contribute to arsenic levels.

(Frank W. Barrie, 4/22/16)

Spring Treat: Cranberry Pecan Waffles With Seasonal Maple Syrup

Maple sugar open house at Five Rivers Environmental Education Center outside Albany, NY: Tapping a sugar maple the old fashioned way

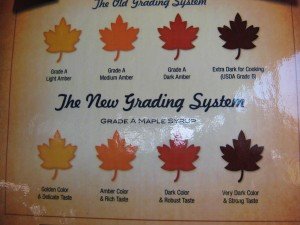

USDA revised grading of maple syrup in 2015: 1) US Grade A Golden, delicate flavor; (2) US Grade A Amber, rich flavor; (3) US Grade A Dark, robust flavor and (4) US Grade A Very Dark, strong flavor.

When the sap begins to run and boiling kettles start producing sweet and savory maple syrup, my mind turns to waffles, hot off the iron, topped with maple syrup. I love the combination of sweet and sour, and maple syrup and tart cranberries are a perfect combo. This recipe for cranberry pecan waffles is a special treat in early spring.

In the late fall, just after Thanksgiving, I stock up on fresh organic cranberries and over the years have been able to obtain Cape Cod cranberries at my local food co-op. Unfortunately, this year the Honest Weight Food Co-op in my hometown of Albany never offered cranberries from the Cape and I settled for organic Canadian cranberries from Notre-Dame de Lourdes in the Lanaudière region of Quebec marketed by Fruit d’Or.

By early April, I was down to one 8 ounce package of fresh cranberries, out of the dozen or so purchased at the end of 2015. With a handful sprinkled into my morning oatmeal as it cooks on the stovetop, cranberries are a part of my daily diet in season and my cache of fresh cranberries goes fast. (Off season, if the craving strikes, I settle for a handful of Stahlbush frozen cranberries, “sustainably grown in the United States,” also sold at the Honest Weight, sprinkled in the oatmeal as it cooks.) A light bulb moment provided the perfect way to utilize my remaining fresh cranberries by cooking up a batch of cranberry pecan waffles topped with this season’s maple syrup.

I take special care in sourcing the few ingredients needed for these delicious waffles and though a sweet treat, they have nutritional value from the organic, stone ground whole wheat pastry flour from Farmer Ground in Trumansburg (Tompkins County, NY), organic raw pecans from The Green Valley Pecan Company in Sahuarita, Arizona, Cowbella plain kefir (cultured milk with its probiotics) from nearby Jefferson (Schoharie County, NY), and Skyhill Farm Eggs from Seward in Schoharie County, NY (no gmo, no soy, certified organic feed from heritage hens hand-raised and free-roaming in garden and pasture). For vegetable oil, I like to use sunflower oil with its mild flavor and Spectrum Organics’ sunflower oil is a 100% mechanically (expeller) pressed refined high oleic oil (with higher concentrations of healthier monounsaturated fats). This naturally refined variety has not been exposed to chemicals like cheaper oils, and has a high “smoke point” making it ideal for the high heat of the waffle iron.

Cranberry Pecan Waffles (makes 7 or 8 waffles)

2 cups whole wheat pastry flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 and 1/2 cups plain kefir cultured milk

2 large eggs

6 tablespoons vegetable oil

3/4 cup pecans (broken up)

3/4 cup of whole cranberries

Heat up 1/4 to 1/2 cup of water in a small sauce pan and add the whole cranberries to cook down into a sauce (about 5 minutes, stirring occasionally).

Place other ingredients in a large mixing bowl and combine until smooth. Add the cranberry liquid/sauce and stir. Batter should sit for a few minutes before using.

Heat up the waffle iron. I use setting 3 of the 5 settings on my iron and cook the waffles for 2 minutes or so until they are golden brown.

Serve topped with seasonal maple syrup and not just any maple syrup! Maple syrup has terroir and there is no doubt that there is variation in its taste and flavors. According to Rowan Jacobsen in his American Terroir, the only suitable terroir in the world for maple syrup is the Greater Northeast, described as a triangle running from Michigan to New Brunwick (Canada) to West Virginia. He explains in fascinating detail how only sugar maples have flowing sap with a “miraculous formula of high sugar content, a few flavor compounds and nothing nasty.”

At the Honest Weight, there are 3 or 4 maple syrups sold in the bulk food department; all produced by Bruce Roblee Adirondack Maple Farms of Fonda (Montgomery County), New York. and the friendly co-op workers, if asked, permit a tasting of the varieties. One always stands out as preferable to my taste buds.

This maple sugaring season, a beautiful drive from my home in Albany, over the Petersburg pass to Williamstown in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, ended at Sweet Brook Farm and a short hike through the farm’s sugar bush before stocking up on a couple bottles of the farm’s delicious maple syrup. How satisfying to know where the syrup for my latest batch of cranberry pecan waffles was sourced!

The northern Berkshires are one of the most scenic spots in the Greater Northeast and Sweet Brook Farm is in the heart of maple syrup country. An added benefit of the farm’s location: just down the road is the renowned Clark Art Institute in Williamstown.

A little over ten years ago, the Institute mounted a memorable exhibit called Sugaring Off, The Maple Sugar Paintings of Eastman Johnson. Johnson, who lived in Fryeburg, Maine, as a child, used the sugaring off season to celebrate New England ingenuity, ruggedness, independence, and community spirit.

Check out our webpage for maple syrup producers and for information on maple syrup festivals. Enjoy knowing where the syrup for your waffles and pancakes comes from.

(Frank W. Barrie, 4/13/16)

Michael Pollan & Alex Gibney Discuss the Making of the Netflix Series Cooked

Pollan contends in his new book that taking back control of cooking may be the single most important step to make the American food system healthier.

The NY Times started up TimesTalks in 1998; many held at The TimesCenter, an auditorium in its new Manhattan headquarters.

While the newspaper business in the 21st century may still be struggling to find a solid financial footing, the New York Times, at least, seems to have found one revenue stream that entertains, enlightens, and also brings home the bacon: TimesTalks, live and webcasted conversations (now in its 18th year) between its journalists and “21st century talents and thinkers.”

In a recent TimesTalks held last month at the Directors Guild of America Theater (an auditorium somewhat larger than The TimesCenter) in midtown Manhattan, best-selling author (and America’s advocate for eating food, mostly plants, and not too much) Michael Pollan and documentary film director Alex Gibney revealed their thinking behind the new Netflix documentary series, Cooked (general admission: $40). The lively, wide-ranging, and nearly 90 minute conversation which included some Q and A, on the pleasures and politics of cooking in an industrial age was time well spent, and well-worth the price of admission.

The four-part Netflix series, based on Pollan’s book, Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation (Penguin Group, New York, NY 2013), makes the case for a return to home cooking and homemade foods by examining and comparing the health implications of several traditional food cultures against our own industrialized food system, in a narrative woven together with Pollan’s detective-like voiceover and scenes from his own journey to become a better cook. In the book, Pollan explored the four classical elements of fire, water, air, and earth, to transform “the stuff of nature into delicious things to eat and drink.” Pollan masters four recipes: (1) pork shoulder barbecue (fire); (2) Samin Nosrat’s meat sugo, a classic Italian meat sauce, and pasta (water); (3) Chad Robertson’s whole-wheat country loaf (air); and (4) Sandor Katz’s version of sauerkraut (earth).

The series similarly explores this process of transformation through in-depth interviews with a handful of artisans who are still making foods in traditional ways; some even came to the talk: the cheese-making nun from episode four, Sister Noella Marcellino; Berkshire Mountain Bakery’s Richard Bourdon from episode three, and South Carolina BBQ master Ed Mitchell from episode one (who would be BBQing with the kitchen crew at Manhattan eatery, Blue Smoke, the next day). And like the book, the Netflix series has a very serious focus, spending significant time showing how the industrialized food system has worked for half a century to make us equate a successful modern life with the freedom from the labors of cooking. But Pollan asks, what better way to spend time is there? What good is saving all that time if we just use it to watch TV and fill ourselves with processed food as we get disconnected from the world and people around us?

In asking such questions, the book and the series arguably can be viewed as equating Pollan’s cause with an almost Buddhist philosophical stance on the nature of mindful living. The audience, a roomful of about 400 New Yorkers, were attentive to the stimulating and thoughtful conversation on the forces that have led to Americans cooking less than half as much as they did in the 1960s, and sympathetic to the need for change.

Moderator and New York Times Food Editor, Sam Sifton, emphasized this main theme early in the night, asking Pollan what those of us with long commutes and long work hours are to do even if we recognize the benefits of returning to the less-processed and more traditional food preparation methods that the series espouses. Pollan’s response was characteristically thoughtful and holistic, showing that he’s spent a lot of time wrestling with the topic and that its answer really is central to tackling many of the crises we face as a society and actually as much about our culture as our cuisine.

Beyond the familiar facts that Pollan is so adept at pulling from disparate fields and weaving into strikingly coherent arguments (and not to mention, catchy mantras) for weaning ourselves off factory farmed and processed food and all its deleterious health effects, Pollan’s latest effort to reach the mainstream differs vastly from his previous works in that it’s anchored in his own effort to be a better cook and it’s focused on the pleasures—not just the health wisdom—of home-cooked foods.

It came as some surprise that someone as food-focused as Pollan, wouldn’t already be a master chef in the kitchen. But from his attempt to feed his friends by slow smoking a pig in an oddly rigged backyard barbeque in episode one to scenes about making beer with his son and overcoming his fear of making bread, Pollan shows us that he practices what he’s preaching and that we too can joyfully retake our kitchens, led by nothing more than our animal senses and humble curiosity. By pushing for a kitchen renaissance rooted in experience and process, he’s not only demonstrating how to reclaim some of the power we’ve handed over to industries that aren’t always looking out for our best interests, but he’s also subtly arguing for a new poetics of living.

To make the series, Pollan entrusted Gibney and his all-star team (who’ve recently produced a string of acclaimed documentaries on Scientology, Steve Jobs, and Enron among others) to find ways to capture these pleasure principles and quite literally bring us back to our senses through evocative and artistic cinematography (not to mention some expert investigative work).

Gibney explained to Sifton that his team intentionally avoided a lot of gratuitous eating shots and standard editorializing, opting instead for a quieter approach that let powerful visuals of the cooking processes leave an impression and give the viewers a chance to make their own conclusions. “The beautiful landscapes and shots of food speak for themselves–as do the industrialized landscapes created by our own unwillingness to cook,” Pollan added, noting that it’s far more effective to lure people into cooking than to lecture them into it.

Despite the many inevitable glamor shots (like the slow movements of smoke wafting from a barbecue in a verdant southern forest that still lingers in my mind), Sifton noted that the series was decidedly not your typical “food porn” style cooking or culinary adventure show. Far from it, Pollan and Gibney said they intended to throw off the usual balance and neatness by including some less filtered moments like the vegetarian who awkwardly tried meat at Pollan’s BBQ along with more visceral footage like the gutting and cooking of a lizard in Australia in episode one, or the Peruvian women, in episode four, who make their traditional alcoholic beverage by chewing yucca root and spitting the pulpy mash back out into fermenting pots (also the subject of a recent National Geographic article by Mollie Bloudoff-Indelicato). In doing so, the series leaves many loose ends but this kind of untidy approach gets precisely at the sometimes contradictory and strange things one encounters on the kind of personal journey and transformation Pollan is espousing.

During the talk, Pollan seemed genuinely pleased by the results of the Netflix documentary and how the material was given a new life and opportunity to expand in the hands of talented filmmakers. For example, he marveled how in episode two, the filmmakers were granted unprecedented access to Nestle’s food labs in India, where they were able to witness the “willful destruction of a great food culture” as food technologists simulate tandoori chicken in a powder.

The breadth of the series gives Pollan ample opportunity to explore and investigate all kinds of food research and traditions, including a few touchy topics that sometimes got him in hot water. Case in point: when “hackles were raised across the nation” (as he put it) when he claimed in episode three that many of the people who believe they are gluten-intolerant would probably be fine if they just switched to eating traditional long-fermented sourdough breads. The logic behind the statement is that, during long ferments, more of the hard-to-digest long-peptides break down than they do in modern fast-fermented breads. Some research suggests these kinds of compounds may be causing digestive inflammation and allowing more gluten to pass into our blood than ever before. One can certainly understand the sensitivity at his self-assured directness but by positing a honest interpretation of the new research, Pollan advances the conversation.

Pollen deftly handled another potentially thorny topic broached by one audience member: the gender implications of Pollan’s call for a return to the kitchen. Would going back to the kitchen represent a step back for women and the decades long struggle to get equal pay and opportunities in the workforce? Foregoing the kind of measured talk I would have expected (given how close the question was to an accusation), Pollan engaged with the topic and also brought up some relevant and revealing bits of oft-overlooked advertising history.

His answer went something like this: It was precisely when the women’s liberation movement was gaining momentum that the food industry began to double down with their pitch for processed foods–positioning them as the solution for working moms to keep their families fed even while their work lives took on increasing prominence (and time). The success of this sales pitch essentially let men off the hook and stopped a new conversation about the division and allocation of household labor from ever really happening. Challenging one of the traditional definitions of male masculinity, Pollan contends that everyone needs to cook–men and boys included (and not just at the primal temple to manly meats that is the grill).

In response to one audience member who asked if he’d ever run for political office, Pollan demurred and offered some persuasive reasons for avoiding the political life and remaining an independent voice for change. After watching Obama’s tenure in office and the tremendous efforts the first lady has made to promote gardening and healthier eating in schools despite “extraordinary” opposition [Editor’s note: Michelle Obama’s American Grown is a book we love], Pollan thinks that there just isn’t enough political capital to fix the problems facing our food system at the deep level that they need right now because, essentially, the game is still rigged.

For example, he explains that someone as seemingly influential as the Secretary of Agriculture is actually captive to the industrial food system because the agriculture committees in Congress that set the department’s budgets and priorities are still exclusively populated by people from states producing food and receiving farm subsidies. Until those committees have representatives from both the food making and the food eating states, the government won’t have much power to change its contradictory status quo of both subsidizing the making of cheap and unhealthy foods on the one hand and subsidizing the treatment of its health effects on the other. It’s a paradoxical and frustrating situation that Pollan explains has resulted in the cost of most processed foods having actually gone down since the 1980s, while the cost of fresh produce has risen by around 40%. Pollan seems content being the outsider voice and making his waves in other more personal ways.

But the night wasn’t all heavy stuff. As a moderator, Sifton kept things moving along with silly asides and by finding ways to lightly rib Gibney and Pollan about some of the series’ controversies and contradictions.

In Cooked, Pollan has yet again succeeded in bringing critical food issues to a much wider audience, who are compelled to confront the modern dependence on industrially processed foods. And, while it’s a tad ironic that he’s telling people to get off the couch and start cooking from the pulpit of a TV show, he makes a powerful case that the myriad problems that Cooked addresses all have one simple solution that we can all do: cook for ourselves. It may seem simplistic but it’s really not: The logic being that when you do, you’ll tend to make healthier food, you’ll tend to eat less, you’ll tend to use better ingredients, and you’ll tend to appreciate your food more.

Far from being mindless drudgery that enslaves us, Pollan wants us to see that growing, preparing, and eating real foods are among the most mindful and meaningful activities we, as humans, can engage in. “We’ve been led to think that these things are in the way of life, but in fact,” Pollan says, “they are life.” After all, Pollan asked the TimesTalk crowd, “Who gathers around the microwave?”

CLICK HERE to link to a video of the Pollan/Gibney/Sifton conversation on the TimesTalks website

(Matt Bierce, 4/1/16)