Archive for February 2016

Hearty Breakfast at OEB and Dinner at Rouge in Calgary, Alberta

Where.CA, a Travel Planner for Canada, named OEB, Best Breakfast in Calgary

A delicious breakfast presents fewer difficulties, than other meals, when it comes to sourcing local ingredients. The fundamental building blocks of diner-style breakfast food — eggs, meats, and dairy products— are agricultural products more readily procured in a sustainable and ethical manner from local purveyors even in a northern climate. Moreover, in the midst of Canada’s wheat belt, where Calgary’s OEB breakfast co. is located, pastries and breads can be made with locally sourced, organic flour milled from wheat grown on Alberta’s plains. According to owner Mauro Martina, OEB uses organic, unbleached all-purpose flour, made from Alberta-grown hard red spring wheat when possible and preferably from Highwood Crossing.

The central component of breakfast at OEB, open since 2009, is the egg. The restaurant’s use of eggs is so great that it operates two large barns to produce the approximately 3,000 eggs the restaurant uses in a week. Its chickens are “free run,” and the restaurant’s materials boast about the “dark yolk, omega 3 eggs” its chickens produce. OEB is so egg-obsessed that it includes an “eggs cracked” counter at the top of its website. Current reading: 619,467. It’s fun to imagine an egg counter button in the kitchen being pressed with every crack though unlikely for practical reasons (and the counter doesn’t update that often, it seems). On a more serious note, this public tracking and awareness of consumption is very appealing. Although OEB seems proud of its prodigious use of eggs throughout its materials, this counter may lead some diners to realize the amount of agricultural resources required to produce their meal. When OEB’s counter reaches 1 million cracked eggs, will it be cause for celebration or further reflection on sourcing practices? (Editor’s Note: In comparison, McDonald’s stopped updating the number of burgers sold back in 1994 at 99 billion; as of March 2010, a blogger estimated total burgers sold of 247 billion. Yikes! FWB)

Rolling up to the warm, inviting space occupied by OEB on Calgary’s north side was a pleasure on the cool, snowy, dark, and foggy morning we spent in Calgary (where in early February the sun doesn’t rise until almost 8 a.m. and the warm Chinook wind blowing down the mountains creates a dense early-morning fog when it comes in contact with the snow-chilled surface). Just inside the doorway is a sign announcing the local ranchers, farmers, and entrepreneurs who provide a large portion of OEB’s raw ingredients. The sign shares thanks with a thoughtful message to these suppliers: your hard work inspires us daily. The restaurant is decorated in a fun, peppy mid-century mod style that pays updated homage to diners of yesteryear. Upbeat soul and Motown music playing through the sound system added to the joyful vintage vibe.

At the early and dark hour we were seated, both the staff (upbeat, all) and we diners were still waking up; the massive front-and-back menu we were given to choose from presented an intellectual challenge. Every dish on the menu was independently appealing. The menu ranges from standard breakfast fare (waffles, french toast, smoothies, basic egg/meat dishes) to the more elaborate dishes we ordered from the My Blue Plate Special part of the menu.

One diner ordered the braised truffled butternut squash with scrambled egg whites, which the kitchen happily substituted in place of the standard two poached eggs. The dish included a truffled squash compote, the restaurant’s standard twice-fried potatoes (fried in organic duck fat), fresh fruit (decidedly non-local, as one would expect given the winter season – the fruit included dragonfruit, more common than you’d expect as a result of the Asian-inspired culinary scene of Western Canada, and kiwi), a brown butter hollaindaise, and microgreens. The dish was excellent; sweet and savory all at once, and filling without being heavy. The potatoes, given the use of duck fat for shortening, had a rich and complex flavor.

The second diner ordered the Wild Boar Spalla, an almost overwhelming dish for this early in the day. Two thick and large pieces of soft and delicious brioche bread were topped with two hen eggs cooked over medium, six month cured wild boar shoulder charcuterie, arugula, finely grated manchego, and a smoked chipotle aioli dressing. This diner was perhaps a bit overzealous in his breakfast order decision-making, but the dish was just as delicious as it sounds. Wild boar charcuterie is a great pleasure as the meat can have unexpected and sweet flavors – this charcuterie was no exception.

These dishes were priced at $14.99 and $15.99 CAD respectively (current exchange rate is $1.38 CAD = $1.00 USD), which seems quite inexpensive for the quality of the ingredients, preparation, and service, and the quantity of food presented. Our overall experience at OEB (originally called Over Easy Breakfast and renamed in honor of its customers’ preferred nomenclature) was excellent and on our flight out of Calgary we bemoaned our single opportunity to eat there. OEB – keep on crackin’!

We also enjoyed a very fine farm to table dinner, filtered through French cooking technique and flavor, at the homey restaurant, aptly name Rouge, situated in a small, two-storied house (built in 1891 and which has always been painted red according to our server) in the middle of a residential neighborhood just east of downtown Calgary. We were greeted by a friendly hostess with a French accent – all staff epitomized the unhurried, garrulous, and friendly nature of other Albertans we met on our trip. Diners are distributed throughout several rooms, each with a handful of tables. We were seated in the house’s original dining room, which had windows looking out at the restaurant’s property. The room was decorated with paintings of the nearby Canadian Rocky Mountains.

Between March and November, the restaurant takes advantage of its large property (which takes up 6 city lots) to grow a good amount of the produce used by the kitchen. There are a number of raised beds in the deep backyard where the restaurant grows all sorts of fresh ingredients for use in its dishes. It’s hard to beat a well-managed backyard garden in terms of local sourcing of ingredients. Out of season, the restaurant makes strong efforts to source local ingredients and places an emphasis on root vegetables, sustainably-sourced fish, locally-sourced meats, and complementary starches.

Diners can select a chef’s tasting menu “for the epicurean inspired by adventure and exceptional food,” $115 CAD per person with a recommended wine pairing ($60 CAD for the standard or $100 CAD for the premium pairings). For visitors from the United States, the advantageous exchange rate made the chef’s tasting menu tempting, but we opted instead to order off the á la carte menu.

Our waiter first presented us with an amuse-bouche – a small puff pastry with an herbed cream cheese filling – a pleasing beginning to the meal. House-baked sourdough bread (made with locally-sourced, Highwood Crossing all-purpose and Heritage Harvest red fife flours, both organic) had a delicious sourness, indicative of a good starter or extended fermentation. The bread course included cultured salted butter and fermented butternut squash.

A salad of salt-baked root vegetables accompanied by port-poached pear, hazelnut butter, pear-hazelnut dressing, and winter lettuces provided a delicious first course. Salt-baking is an ancient, although unusual and recently trendy preparation where the food is cooked in a layer of salt that locks in moisture and flavor and also seasons the food inside – our waiter described the process of cracking the root vegetables out of their salt shell after baking. This preparation gave the root vegetables (primarily beets) an even, saline flavor that was pleasing in a dense, but not overwhelming, way. The poached pear and pear dressing provided a sweet compliment to the savory vegetables.

We ordered two entrées. The first diner ordered a lamb loin from Driview Farms, which came with lamb neck confit, root vegetables, gnocchi, hazelnuts, and béarnaise. The dish was well balanced, and the gnocchi were especially delicious. The second diner ordered a piece of Icelandic cod, recommended by the Vancouver Aquarium as an Ocean Wise fish, which indicates the seafood is considered to be ocean friendly. (This certification and its accompanying symbol is featured throughout menus in Alberta and British Columbia as a marker of sustainable fisheries, and many restaurants embrace serving seafood that is sustainably caught, as evaluated by this program.) The cod was served on top of mashed potatoes with some roasted sunchokes, cippolini onions, and fine waffled potato crisps. The cod was flaky and well flavored and the accompaniments added a hearty, and savory balance to the dish.

Even in the wintry month of February, Rouge is well worth a visit. In season, when its backyard garden is providing ingredients for its French inspired menu, the fair weather tourist is in luck given the culinary skills, so ably demonstrated off-season, and Rouge’s friendly and attentive wait staff.

OEB breakfast co., 824 Edmonton Trail NE (just south of 8 Avenue NE), 403.278.3447, All Day Breakfast/Brunch: Mon-Sun 7:00AM-3:00PM (kitchen closes at 2:45PM)

Rouge, 1240 8th Avenue SE, 403.531.2767, Lunch: Mon-Fri 11:30AM-1:30PM, Dinner: Mon-Sat 5:00PM to close

(L. Bregman & D. Barrie, 2/22/16)

Longer Lives for Dogs: Know Where Rover’s Food Comes From

Dogs wear no shoes and put their noses to the ground: appreciative of a pesticide free lawn in the Buckingham Pond neighborhood in Albany, NY

Open field in downtown Albany,NY’s Washington Park where city dogs can enjoy the freedom of running off-leash

Kerasote’s two childhood dogs came from animal shelters and he struggled with his decision to find a houndy looking lab from a breeder

A food co-op committed to a “food policy” which considers “moral & ethical production, environmental stewardship, healthy living and safety,” like Honest Weight in Albany, NY is a good place to shop for a dog’s food

Twenty-five years ago in 1991, a houndy looking lab, with some golden retriever thrown in, wandered into Ted Kerasote’s campground along the San Juan River in Utah, about 100 miles down the road from Moab. This 10 month old, half-wild mixed breed, named Merle by Kerasote, became his loving companion in a person-dog relationship that would last for a too-short 13 years. Merle died of glial cancer in 2004.

Ted Kerasote, during his four decades career of writing and photography, has written on the interrelationship of people, animals and the natural environment. In this fine writer’s words, he discovered the sweetest remedy for grief by snatching Merle from time’s dissolution and turning him into story. Kerasote sifted through his memories and steadily wrote over a period of nearly three years. His national bestseller, Merle’s Door, Lessons from a Freethinking Dog (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008) touched the hearts of many readers and earned the respect of dog lovers, including Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, author of The Hidden Life of Dogs, who said it could be the best book ever written about dogs.

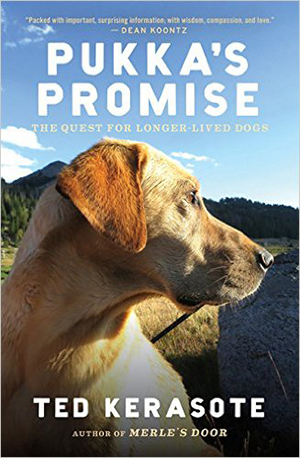

Kerasote writes in his latest book, Pukka’s Promise, The Quest for Longer-Lived Dogs (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) that Merle’s death “had inoculated me against any other dog for years. . .” But in 2008, four years after Merle’s death and after the publication of Merle’s Door, he decided: “I wanted no empty couch. I wanted no silent house, I wanted another dog in my life.” Closely tied to this desire for another canine companion, Kerasote embarked on a mission to learn about the “healthiest ways to raise our dogs and to find my own new dog.”

Kerasote’s quest to find out why dogs die so young (only 1/8th the human life span) was also prompted by the hundreds of e-mails, “many of them heartrending,” he received from readers who had lost beloved dogs. In particular, readers questioned why their dogs were dying of cancer, mirroring Kerasote’s concern:

“Merle’s best friend Brower, a Golden Retriever, was diagnosed with a malignant cancer of the snout when he was six. Another of Merles’s good friends, a black Lab named Pearly, died at seven of a neurofibrosarcoma that began in a nerve root at the base of her neck. Merle himself, though no young dog at fourteen, finally succumbed to his brain tumor.”

Kerasote’s search for his new dog, detailed in his latest book, reflects the laudable work of an accomplished and thoughtful writer, assisted by six researchers. Pukka’s Promise (Pukka meaning “first class” in Hindi) tells not only a terrific story, but, with its 49 pages of footnotes, rises to the level of a reference book for anyone seeking guidance on how to find, raise and love a canine companion. As noted by Jon Katz, the author of A Good Dog, Pukka’s Promise “stirs our hopes for the future.”

Domestic dogs in the United States, estimated to number somewhere between 60 to 77.5 million, share 99.9% of the DNA of wolves. In the wild, wolves live no more than three or fours years, while in the safety of captivity, wolves can live as long as a big domestic dog, from 12 to 14 years.

Kerasote notes the differences in longevity among dogs, with small and medium sized dogs living longer than large ones (which die often before 10 years old) can be genetically explained. In the mid 2000s, it was discovered that all small dogs have a tiny mutation of the gene called IGF1 and produce less of the protein IGF-1, than larger dogs, so that insulin levels of smaller dogs fall and life span increases.

But it’s not only genetics that determines the life span of dogs. The following seven factors, which Kerasote thoroughly examines, affect dog health and longevity. And they provided the basis for his decision on what dog would become his companion and how he would raise his new canine friend: inbreeding, nutrition, environmental pollutants, vaccination, spaying and neutering, the shelter system in which too many dogs end their days and the amount of freedom dogs enjoy.

Kerasote notes that a great number of people believe it’s morally wrong to do anything but adopt a dog given that 1.5 million healthy dogs are put to death each year in American shelters. But he knew if he got a dog from a shelter, it would almost certainly be spayed or neutered, “potentially reducing my chances of giving it the longest life possible.” According to his research, spayed and neutered dogs experience more adverse reactions to vaccines, a higher incidence of some cancers, suffer more orthopedic injuries, have a greater propensity to endocrine dysfunction and are more obese. Kerasote is an ardent advocate for vasectomies and tubal ligations, which allow a dog to retain its beneficial sex hormones, as alternatives to spaying and neutering.

Because mixed-breeds or crossbreeds don’t make breeders much money, Kerasote couldn’t find a single breeder turning out a houndy looking lab, and he turned to breeders of labradors. He needed “a big enough dog to join on hikes, climbs and mountain biking trips in summer and big enough not to be coyote bait.” He also sought a dog that would be calm and intelligent, love the cold and high places, and could navigate deep snow without its paws clogging. A labrador could potentially fit the bill for a rangy, athletic dog that could track well (a dog’s extraordinary sense of smell is up to 100,000 times more acute than a human’s) as retrieve. It’s fascinating that Kerasote’s final test in selecting Pukka from a litter of pups is his own sense of smell: “The darker pup smelled rich-like lanolin with a hint of nuts-a faint remembrance of Merle, of hounds, of Golden Retrievers. . . I wondered if on some unconscious level, some pheromonal level, I had been drawn to the darker pup for this very reason. I’ve alway trusted my nose when it comes to decisions of the heart. . . among all our senses the most difficult to fool.”

Given his decision to find a breeder of labradors with a pup that would meet his needs, Kerasote’s discussion of the health consequences of inbreeding were of particular significance:

“Selecting for certain characteristics in dogs. . . not only produced dogs with differing life spans. It also caused dogs of every size and shape to be more inbred and thus prone to a variety of genetically linked diseases. About four hundred of these conditions have now been cataloged in purebred dogs. . . .” One striking example: 100,000s of North American Golden Retrievers are descended from three champions and have received both their sweet dispositions and their hidden time bombs: a survey conducted by the Golden Retriever Club of America and the Purdue School of Veterinary Medicine notes that 61.4 percent of Golden Retrievers die of cancer.

Kerasote discovered that it was “easy to find out,” by calculating the coefficients of inbreeding (COIs), how inbred (and therefore how potentially disease-prone) a litter of pups might be. By using a computer program from PedFast Technologies that cost a little more than $10.00, his goal “was to find litters who had COIs of less than 6 percent.” One nonrandomized survey of Standard Poodles found by Kerasote that contained 349 records showed poodles “who had a COI of less than 6.25 percent lived nearly four years longer than those dogs whose COI was greater than 25 percent.”

Also important when buying a pup is to visit the place where it was bred in order to evaluate the puppy’s temperament. Kerasote writes: Interacting with the parents of your prospective puppy as well as its breeder can tell you more about what sort of dog you’re going to live with.

Of the seven factors, noted above, analyzed insightfully by Kerasote, of special interest to this reader was his advice on a dog’s nutrition. He notes that it is not cheap to provide healthy, nutritious food to a dog. In the first year and a half, as Pukka went from a fourteen-pound puppy to a seventy-pound dog, and when he was “the equivalent of a rapidly growing teenager- he would eat between five and seven pounds of meat, bones, and vegetables in a day . . . or 9 to 13 percent of his body weight.” Kerasote estimates the yearly cost of $2,500 for his preferred commercially prepared, AAFCO-certified raw food diet, “almost all of whose ingredients are free-range and organic.” He understands that, according to surveys by the American Pet Products Association, the average American spends $229.00 per year- 67 cents per day, on dog food, and that a popular kibble from a big-box store certified by AAFCO, would cost even less than that average, at $150 annually. However, that would mean a beloved dog would be fed a kibble “whose first ingredient is corn and which also contains wheat middlings, soybean meal, brewer’s rice, and animal fat preserved with BHA, along with the artificial colors yellow #5, yellow #6, red #40, and blue #2.”

Pukka’s Promise includes nearly 70 pages focused on a dog’s diet organized into four insightful chapters. Kerasote cites to the writings of three veterinarians, Dr. Ian Billinghurst, the Australian founder of the raw food movement, Dr. Marty Goldstein, a champion of raw-food diets, and Dr. Karen Becker, who started the widely read website Mercola Healthy Pets, as well as Ann N. Martin, the author of Foods Pets Die For (who it has been said by Dr. Michael Fox “is to the pet food industry what Rachel Carson was to the petro-chemical-pesticide industry”).

Chapter 12, Carnivore to Monovore, begins by noting what real wolves eat: the answer short and simple, wolves are 98% carnivore. Then applying a fascinating, historical perspective to his analysis, Kerasote cites the 19th century, Scottish-born medical doctor and dog fancier Dr. William Gordon Stables, who cautioned against overfeeding grains. But Stables didn’t limit a dog’s diet to meat, and was “adamant” that “dogs needed vegetables at least three times a week: cabbage one day, kale the next, then turnips, and so on.” Kerasote’s description of the beginnings of the commercial pet food industry shows that “marketing and advertising” early-on justified replacing a diet of raw meat, bones and vegetables with manufactured biscuits and specialized dog foods made with “what other industries considered their waste products-grain husks, meat trimmings, worn-out livestock, dying draft animals.”

With a critical eye applied to the over $15 billion dollar pet food industry, as well as vivid descriptions of his visits to rendering facilities and his frustrated attempts to tour the facilities of major manufacturers of dog food kibble, Kerasote rejects high-carbo, corn-based kibbles, which raise blood glucose levels quickly. He cites research that demonstrates that reducing the amount of starch in canine diets helps to manage problems of canine obesity and diabetes. Reducing “the inflammatory chain reaction,” which leads to degenerative diseases associated with aging (such as cancer, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, allergies and autoimmune disease), can be achieved with a diet that includes, for example, raw meaty bones, chicken carcasses, and ample green leafy vegetable citing the advice of Dr. Billinghurst.

In a later chapter, Real Food, Many Forms, Kerasote’s summarizes his decision to feed Pukka an AAFCO-certified raw food diet, with one major caveat. He describes testing three commercial kibbles, five commercial, frozen raw-food diets and two dried ones for lead, and found no detectable level of lead in only three. His concern about heavy metals in foods, dog or human, confirmed by this testing, reinforced the wisdom of what Dr. Joe Bartges, on the faculty of The College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Tennessee, told Kerasote: to rotate a dog’s food so as “minimize the risk of feeding the same heavy metals year after year.”

The Cornucopia Institute, which supports ecological principles and economic wisdom as it advocates for sustainable and organic agriculture, deserves much credit for developing a Pet Food Guide. In a recent newsletter, the Institute pointed out that “Pet food quality varies significantly and all too often includes dangerous chemical additives.” Kudos to the Institute for its “thorough analysis of the pet food industry” and its report and guide to pet food. Also appreciated is the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) recent bid to regulate animal food (reported in the New York Times by Sabrina Tavernise), acting for the first time, after recall and deaths. Since 2007, the FDA has counted about 580 pet deaths, nearly all dogs connected to jerky treats, nearly all imported from China. Dog lovers can remember well the biggest pet food recall in history in 2007 when a Chinese producer contaminated dog and cat food with melamine, a compound used in plastics, causing the deaths of animals across the United States.

As a closing note, this past summer, Ted Kerasote announced to his “friends and readers” that the “moment may happen soon” for Pukka to sire a litter, and he is seeking a suitable mate: “a dark yellow or fox-red Labrador Retriever, who has completed all her health certifications.” He has created a website, www.breedingpukka.com, which contains all the relevant information needed for breeders to see if Pukka is a good match for their female. Might a new book be gestating in Kerasote’s mind too? For his readers, let’s hope so.

(Frank W. Barrie 2/9/16)

Field Goods Celebrates Its New Distribution/Warehouse Facility in NY’s Hudson Valley

Fresh foods from small farms is the praiseworthy tagline for Field Goods, a direct-to-consumer, food distributor in upstate NY’s rural Greene County. On a late January day, in a remarkably mild upstate New York winter, this locally grown business (supported by an Empire State Development grant through the Capital Region Economic Development Council) celebrated its new 18,000 square foot home in a renovated warehouse. The new space, which includes 4,000 square feet of refrigerator and freezer storage, ensures the continued growth of Field Goods, which delivers food grown by small farms to consumers in a service area that “spans 13 eastern New York State counties from Queensbury (Warren County) in the north to the Bronx, as well as Connecticut’s Fairfield County, in the south.”

Field Goods founder and president, Donna Williams (a former investment banker and business development consultant with an MBA from Columbia University and family roots in Greene County), in her opening comments at the ribbon-cutting for the new facility, noted that the business just had its biggest sales week ever, delivering 2200 bags of produce from small farms to its subscribers. The business offers weekly deliveries of fresh local produce to consumers at two types of delivery locations, private sites (generally workplaces) and open-to-the-public sites (such as gyms or libraries, where anyone can stop by to pick up a bag).

Group deliveries help the operation keeps prices low. Four sizes of fruit and vegetable subscriptions are available, at a cost of $15, $20, $25 and $30 per week for (1) fruit and vegetable subscription, designed for one person; (2) fruit and vegetable subscription, designed for 1 to 2 people; (3) fruit and vegetable subscription, designed for 2-3 people; and (4) fruit and vegetable subscription, designed for 3-5 people, respectively.

Field Goods has been successful in marketing its delivery of fresh food to employers as “a valuable wellness program and employee benefit.” A creative 10-week program, priced as little as $50 per employee, includes the weekly delivery of 6-8 local produce items, a weekly educational newsletter, and an introductory group presentation. Also of value (in addition to encouraging employees to improve their diets) is the support demonstrated for small farms and sustainable agriculture by participation in the program.

During the week of January 25th in the darkness and cold of winter (when Field Goods had its biggest week ever), the following small farm, local products were delivered to subscribers (in all bag sizes): frozen broccoli and fresh brussel sprouts from Shaul Farm, frozen sweet corn from Dustry Lane Farm, carrots and fingerling sweet potatoes from Juniper Hill Farm, and fuji apples from Yonder Farm. In small, standard and family bags, these additional items were included: greenhouse grown mix of crisp red and green romaine lettuce, kale, spinach, tatsoi and komatsuna from Radicle Farm and red onions from Minkus Farm. Subscribers had the option to include in their food bags for the late January week, at an additional cost, the following items: rosemary, leeks, Asian pears, mozzarella cheese from R & G Cheesemakers, bread from Bread Alone, fresh pasta from Knoll Krest Farm and yogurt from North Country Creamery.

On its website, Field Goods notes that “our farmers use a variety of farming methods, all of which are designed to produce the most nutritious, delicious and sustainable products possible.” Specific information is provided to consumers showing whether the particular product in the weekly bag are either certified organic, organically grown but not certified, IPM (Integrated Pest Management), or conventional small farm methods. For example, in the bags delivered during the week of January 25th, the fingerling sweet potatoes and greenhouse mix were noted as certified organic, the frozen sweet corn was IPM, and the other products were grown with conventional small farm methods. Special mention should be made concerning how Radicle Farm, in the upstate city of Utica, by growing greens, on 16 acres under glass, has helped to create a substantial economic presence in a post-industrial, small rust-belt city.

Present at the ribbon cutting were state and local lawmakers, as well as writer Molly O’Neil, a former New York Times food columnist who shared information on the Long House Food Revival (known as the Woodstock of Food), cooknscribble (an online teaching platform for food media professionals), and her current involvement in the revitalization of the small, rural village of Rensselaerville (Albany County, NY), as well as Modern Farmer editor Sarah Grey Miller. O’Neil made introductory remarks for a roundtable discussion by a panel of farmers, which was moderated by editor Miller and Todd Erling, the Executive Director of Hudson Valley AgriBusiness Development Corporation based in Hudson (Columbia County, NY). Topics ranged widely and included (i) food safety, (ii) utilizing the CSA model to support the economic sustainability of farms, (iii) the need of more traditional farms for migrant labor and (iv) GMOs.

The outpouring of support for Field Goods from Greene County and neighboring Hudson Valley communities demonstrates the appeal of an enterprise that has the potential to stimulate economic activity in a geographic area (as well as improve the diets of consumers). According to an insightful report prepared by Dr. Rebecca Dunning, the Project and Research Coordinator for the Center for Environmental Farming Systems at North Carolina State, numerous studies indicate that fruits and vegetables produced and consumed locally create more economic activity in an area than does comparable food produced and imported from a non-local source. Perhaps this is obvious, but the reach of the increased economic activity may not be so simple: in addition to income generated directly by farm sales or at nearby farmers markets (or in the case of Field Goods by a creative entrepreneurial business providing a consumer market for 50 small, local farms), income is also generated locally from “induced income that results when money that is retained in the local system is re-spent locally.” Further, the resulting increases in employment, from the local production and consumption of food, supports and sustains “small family businesses engaged in building the entrepreneurial culture of a community” as noted in Dr. Dunning’s report.

(Frank W. Barrie, 2/1/16)