Archive for December 2015

Delicious Farm to Table Dining in Orlando, Florida

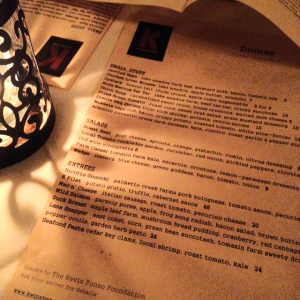

Roasted half of beef marrow bone piled up with ruby red tar tar as described on the menu (tartare?).

With 62,000,000 visitors annually, Orlando, Florida is the most visited tourist destination in the United States. But while its theme parks beckon millions, our listings of farm to table dining options in Florida are not many in number. But there is one particular dining destination in the Orlando metro area that deserves kudos for its commitment to local food sources and the good food movement: K restaurant, located just north of downtown Orlando, in the heart of the College Park neighborhood.

K restaurant (named for its chef/owner Kevin Fonzo, who trained at the renown Culinary Institute of America [C.I.A.] in Hyde Park in the Hudson Valley of upstate New York) is worthy of a special trip for the visitor as well as a destination for an Orlando area resident. A farm to table restaurant, located in a freestanding house with a wrap around porch and space on the grounds for a sizable vegetable and herb garden, this Florida restaurant is an inviting destination for diners who desire delicious food prepared with ingredients that are carefully sourced. The restaurant’s website includes information on the farms which provide ingredients used for the dishes on the restaurant’s menus, which change daily.

On entering, a shelf of unwrapped soaps, which look like miniature Jackson Pollock paintings, attract close attention. “Those are hand-made by one of our servers,” chimes the hostess who noticed our interest. If it weren’t for the bar and tables, the warm greeting, hospitable homey environment, and hand-made soaps made me think I was stepping into a creative friend’s home for a family dinner.

Chef/owner Kevin Fonzo has created a dining atmosphere that reflects a generous spirit, which extends to his home community. Notably, he volunteers at the Orlando Junior Academy, a small school in the College Park neighborhood, as a committed participant in the Chefs Move to School program, an initiative started by First Lady Michelle Obama to enlist chefs in the fight against childhood obesity. [Editor’s note: One of our favorite books in recent years is Michelle Obama’s American Grown, The Story of the White House Kitchen Garden and Gardens Across America (Crown Publishers, a Division of Random House, Inc., New York, New York 2012). A beautifully designed book, full of wonderful photographs (many by photographer Quentin Bacon), provides a lively history about the White House gardens and landscape, much insight on how to grow your own food, and a positive plan for addressing our nation’s obesity epidemic, and was previously reviewed on this website (FWB).]

The Chefs Move to School program assists chefs in adopting a school and working with teachers, parents, school nutrition professionals and administration to help educate children about food and to show them that healthy eating can be fun. One school year, chef Fonzo worked in the Orlando school’s cafeteria every day, preparing fresh, healthy lunches utilizing ingredients from the school’s garden. He continues to share his knowledge and skills at the school, and now every Thursday volunteers for a full teaching schedule for the day. He uses cooking instruction as an integrated education method, where the students learn about nutrition, biology, chemistry, practice math skills and the cleanliness and discipline necessary for a culinary career.

Freshly chopped garlic and herbs tease the nose as we’re led through the gently lit dining room to our table. Our server continues the familial treatment, suggesting his favorite dishes and informing us that the seasonings we smell are from the bountiful backyard garden. His favorite phrase to describe the food is “on point,” and he’ll get no debate. The dishes served at K restaurant will perfectly satisfy our search for excellent, “spot on” farm to table dining in the Orlando, Florida area.

My dining companion and I start with three appetizers. A delicious seafood appetizer of green tomatoes fried in a cornmeal crust and layered with sweet crab salad is lightly sweet, with a touch of savory grain mustard. The crab is divine and uncompromisingly fresh. Our server notes that K restaurant doesn’t have a walk-in cooler or large freezer system like most restaurants and most ingredients arrive at the beginning of the day. Arancini (fried rice balls) stuffed with Palmetto Creek (a family owned and operated farm, which “started as a family 4H project that totally changed our lives for the better”) pork sausage follows. These delicious treats burst with flavor. Kale and roast garlic accentuate the risotto in perfect proportion. A third appetizer of bone marrow tartare, made with beef from Lake Meadow Farm, is a truly inspiring dish consisting of a colossal beef bone sliced in half and roasted. The buttery marrow is topped with gorgeous ruby tartare, diced tomatoes and herbs. We slather the accompanying crostini with the beef bounty and finish off every morsel. These appetizers could have easily been enough for two as dinner, given the generous size of the servings.

We refresh our palate by sharing the kale caesar. Sourced from the backyard garden, the salad is dressed lightly in a sumptuous, classic Caesar dressing. It’s the perfect respite between our rich first courses and the main events, wild Pacific Northwest salmon and duck breast.

The salmon prepared medium-rare upon recommendation by our server, rests atop buttery parsnip purée. A bacon salad, featuring Frog Song Organics’ radish, garnishes the fish. An impeccable dish! I debated between it and the snapper, the local day boat catch. Though inclined to try the east coast Florida fish, our server’s enthusiasm and the promise of bacon salad tempted me otherwise. I will have to try the snapper on my next visit. The duck breast from Maple Leaf Farm (based in Indiana) accompanied by a mushroom bread pudding, red cabbage, and cranberry, was cooked to perfection and its cranberry tartness especially pleased my dining companion.

For dessert, the pecan pie and creme brulée were delicious sweet endings to the meal.

After dinner, we take a stroll to the garden out back (a wonderful setting for the restaurant’s wine tastings, pig roasts, oyster roasts, and even weddings). Serendipitously, chef/owner Kevin Fonzo, watering the garden, graciously offers us a quick tour, pointing out lemon verbena and rosemary, the sweet potatoes he has just dug up this week, recently harvested grape vines, bushy kale plants, and plump pumpkins. Offering us a glass of white wine, we sit at a patio table and this remarkable man shares the history of K, from its conception 15 years ago to its expansion and its eventual move to its current location. His volunteer work at the local school will soon expand to include beehives, a second garden plot, compost pile, and a worm farm; how awesome, like our meal! With its impressive food and the congenial, laid-back atmosphere, K restaurant is a destination restaurant worthy of return visits.

[K Restaurant, 1710 Edgewater Drive (across from the post office), Orlando, 407.872.2332 Lunch: Tues-Fri 11:30AM-2:00PM, Dinner: Mon & Tues 6:00PM-9:00PM, Weds-Sat 6:00PM-10:00PM]

(Lucas Knapp, 12/21/15)

The Art of the Farm: Lavern Kelley’s Folk Art

Retrospective solo exhibit of Lavern Kelley’s folk art at the Fenimore Museum on display until 12/31/15

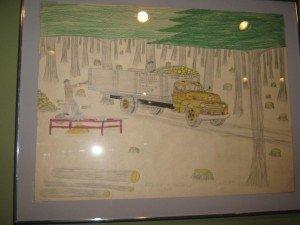

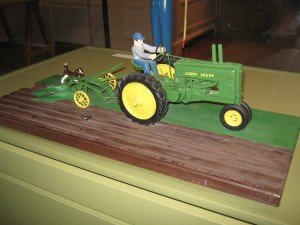

Kelley, who never learned to drive a car or had a license, loved the John Deere tractor; Note the carved dog & bird in this farming vignette

Farmer artist Lavern Kelley (1928-1995) and his brother Roger, neither of whom married, lived their entire lives on a 230 acre dairy and livestock farm, in the village of Laurens just outside Oneonta (Otsego County) in upstate New York, which had been their family’s farm since the late 19th century. Twenty years after his death, Lavern Kelley’s art is now on display (until 12/31/15) in a retrospective exhibit, Lavern Kelley: The Art of the Farm, at the Fenimore Museum in Cooperstown (Otsego County, NY).

Patterson Sims, the Guest Curator, in his essay accompanying the exhibit, notes that Kelley “never had any formal artistic training, nor wanted it.” Kelley’s art, according to Mr. Sims, is rooted in his “deep conviction in the fundamental verities, values, and historic centrality of farming and rural small town and community life.” It wasn’t until the 1980s when Kelley was in his 50s, that he began to understand he was “an artist,” and in 1989, his art was the subject of a solo exhibition at Hamilton College’s Emerson Gallery (now the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art). Nearly three decades later, the art of Lavern Kelley has earned this second museum show. Farmer artist Lavern Kelley also received recognition in the late 1980s when he was invited to demonstrate his woodcarving techniques at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. To do so, Kelley took his first and only train ride, traveling between Albany (a long hour’s car-drive from his Oneonta area farm) and New York City, where he flew on to Santa Fe.

Lavern Kelley was a teenager when farming in the 1940s in upstate New York changed from horse to mechanical power, and he was fascinated, if not obsessed, with John Deere tractors. In his words: “Plowing with one of these tractors was actually an event to look forward to, whereas doing so with horses was usually, at least by me, dreaded.” Little surprise that his artistic accomplishment would include (by the mid 1970s) over 450 painted carved trucks and tractors, which he displayed in a special shed near the family farmhouse. The hundreds of trucks and tractors “in tight formation,” according to Patterson Sims, “looks like a folk art, sculptural version of an Andy Warhol Pop-Art painting with massed Coca-Cola bottles or Campbell’s soup cans.”

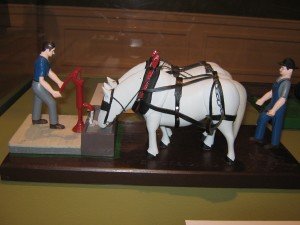

By the mid 1980s, Kelley’s subjects for his skillful wood carving had expanded from trucks and tractors to include animals (cows, pigs, horses, dogs, cats and birds) and human figures as well as farming vignettes. Although plowing with horses was “dreaded” by Kelley, one of his farming vignettes on display, A Drink Before Going to Work (1990) is a throw-back to earlier days on the Kelley farm. [In fact, horse-powered farming has become appealing of late for “small-scale, resilient farming with a closed-loop system” in the words of Stephen Leslie of Cedar Mountain Farm, the author of The New Horse-Powered Farm (Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, 2013).]

Kelley also began to make formal photographic portraits in the late 1970s, and more extensively through the final years of his life, of his carvings positioned out of doors on the farm with hand-written commentaries beneath the enlarged prints. Curator Sims observes in his essay that Kelley’s staging of photographs demonstrates a “formidable intellect, clarity, and idiosyncratic artistic talent.” Sims compares Kelley’s photography to that of William Wegman, Duane Michals, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Gregory Crewdson, who employed “photography to stage images using real and make-believe surrogates and backdrops.”

For this visitor, of particular interest were Kelley’s color pencil and crayon drawings from the late 1940s of the mindful harvesting of wood from the family farm’s woodlot. They brought to mind Wendell Berry’s novel Jayber Crow where a treasured woodlot of 75 acres of very good timber, known as the Nest Egg, was greedily clear-cut for a few fast dollars. Kelley’s drawings show no such wrongheadedness on his family farm. His words, displayed near these appealing folk art drawings, echo appealingly in this modern era of maximizing quick profits: To a farmer, a good woodlot was alway an emergency source of income when hard times hit home. The farm woodlots were loaded with lumber. My brother and I would cut it, skid it out, and sell it in the log. We cut only the trees we wanted to cut, leaving the others to grow. Whenever we sold it on the stump, they took everything.

And in this era of human snow birds flying south, the words of Lavern Kelley (rooted in his rural, upstate New York farm) on his love of winter are valued by anyone who also appreciates the changing of seasons: Winter used to be my favorite season. . . We cut wood every winter, and I loved that, then we burned wood for fuel, both for heat and to cook, so it was essential to cut forty to fifty cords each year. In the wintertime, with all the livestock we had, it took most of the day to do just the barn and hens and hog chores, so if [we] managed to cut wood for two or three hours a day, that was about all the time [we] had. The long evenings were always pleasant for me. After chores, we would have our supper, then I usually would draw pictures till bedtime.

As a closing note, in the gift shop at the Fenimore Museum, hand-cut wooden trucks by Sharon and Joseph Benesch honor the memory of Lavern Kelley. Joseph Benesch, who has been working with wood all of his life, using oak, black walnut, ash, and cherry, hand cuts, laminates and hand fits trucks together while Sharon Benesch stains and paints.

[Lavern Kelley: The Art of the Farm, September 19-December 31, 2015; Fenimore Art Museum, 5798 State Route 80, Cooperstown, NY]

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/14/15)

Local Newspaper Asks: Who’s Making Trader Joe’s Food?

A little over three years ago, Trader Joe’s opened a store in the Capital Region of upstate New York. For years, a group called We Want Trader Joe’s in the Capital District, organized by Bruce Roter, a professor at the College of St. Rose in my hometown of Albany, campaigned to bring the national chain to the area. Sponsoring field trips to the Trader Joe’s store two hours away in Amherst, Massachusetts, and savvy use of the local media, Prof. Roter earned recognition in the summer of 2012 when Trader Joe’s opened in the Albany suburb of Colonie. According to the story in the Albany Times Union about the opening of the store, Prof. Roter and other members of his group, wearing T-shirts reading “We Brought Trader Joe’s to the Capital District!,” lined up with Trader Joe’s employees “as the first customers poured inside, high-fiving them and shaking hands.” (As a side note, Prof. Roter is currently campaigning for the creation of A Museum of Political Corruption in the state capital of Albany, too often in the news for self-serving politicians on the take.) Trader Joe’s store in Albany’s suburb of Colonie seems very busy and successful.

Cheap food drives the food choices of many consumers, and Trader Joe’s has established a reputation for food bargains. Its local reputation for cheap food has become so pronounced that the Albany Times Union recently ran a fascinating story, Who’s making Trader Joe’s food? An investigation of the secretive grocery chain. The reporter, Amy Graff, focused on 11 food items, ranging from organic canned diced tomatoes to mini peanut butter sandwich crackers. Her report suggests that the very successful chain sources “its own products . . . from well-known brands and sells them under the Trader Joe’s sub brands at a discount.”

Part of this website’s mission is to promote CSA farms (where a consumer purchases a share in a farm’s bounty before the growing season starts), farmers markets, and food co-ops which stress the sale of locally grown and produced real food. (And the Capital Region is fortunate to have a thriving food co-operative, the Honest Weight Food Co-op, which is one of the few left in the United States that still maintains a member labor program, recently reinvigorated by its members.) The local co-op addresses the concern of consumers for cheap food by publishing an informative, handy guide, Eating on the Cheap, Smart Ways to Stretch Your Dollars. Offering ten tips, ranging from stocking a pantry with food from the co-op’s extraordinary Bulk Department where beans, nuts, grains, flours and much more can be found, eating what’s in season and DIY (do it yourself by making by hand with a bit of preparation and know-how what we buy at the store, such as bread, beverages, cleaning products). Consequently, the Trader Joe’s food items researched by reporter Graff, mostly processed food items, don’t get my food dollar.

And there’s an important economic reason why spending food dollars at a farmers markets or at a food co-op is preferable. According to American Farmland Trust as reported earlier for every $10.00 spent on local food at a farmers market, “farmers get close to $8.00 to $9.00 of the money spent compared to $1.58 farmers and ranchers receive of $10.00 spent on food in general. Plus for every $10.00 spent at a farmers market, studies show as much as $7.80 is respent in the local community supporting local jobs and businesses. Further, the decision to spend food dollars at a food co-op rather than a conventional grocery store also makes better sense for the local economy.

According to a report, Measuring the Social and Economic Impact of Food Co-ops, issued by Co + op, stronger together which represents 134 National Cooperative Grocers Association (NCGA) co-ops nationwide, there is a much greater “local impact” when food dollars are spent at food co-operatives instead of conventional supermarkets. Purchases “locally sourced” represent 20% of purchases for food co-operatives compared to 6% for conventional supermarkets, with local suppliers averaging 157 for food co-operatives verses 65 for conventional supermarkets. Similarly, a conventional grocer spends 72% of each dollar of revenue to purchase inventory, but only 4% is spent on locally sourced products, while the average co-op spends 62% of every dollar in revenue on inventory, 12% of which is spent on locally sourced products. Co-ops spend a lower % of every dollar in revenue on inventory than conventional grocers because the wages of co-op employees average 7% higher than wages of employees of conventional grocers and co-ops employ more people, with 9.3 jobs for every million dollar in sales compared to 5.8 jobs per million dollars in sales of conventional grocers.

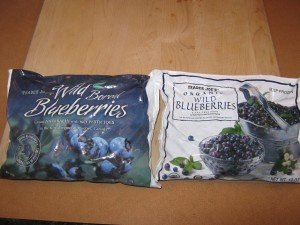

Nonetheless, on a recent visit to the local Trader Joe’s, two real food items, albeit frozen food, caught my eye, as the seasonal fruit disappears from farmers markets (though I’ve stockpiled a nice supply of organic apples and cranberries). Trader Joe’s Wild Boreal Blueberries described as “Grown NATURALLY with NO PESTICIDES in the Boreal region of Quebec, Canada” at the bargain price of $3.49 for a 16 oz. (1 Lb) package and Trader Joe’s Organic Wild Blueberries grown in Eastern Canada described as “firm, ripe berries, small in size, but big in sweet tangy flavor” at $3.49 for a smaller 12 oz package were worth some of my food dollars. They’re sure to be enjoyed in a bowl of hot oatmeal on a wintry morning. Alas, these wild or organic Canadian berries purchased at Trader Joe’s are an exception to my general rule of spending my food dollars by purchasing a share in a CSA farm’s bounty, in my case Roxbury Farm in Kinderhook (Columbia County, NY), shopping at farmers markets and at my local food co-op.

(Frank W. Barrie, 12/10/15)

Savoring the Wild & Wonderful at London’s Rabbit

Slow cooked venison (of a deer that was eating Nutbourne Farm’s organic crops) served with pici (fat spaghetti) pasta garnished with wild foraged nasturtium leaves

In London these days, you can’t help but run into one of celebrity-chef Jamie Oliver’s many shiny new restaurants. These outposts of casual upscale dining are both billboard and beachhead for Oliver’s so-called food revolution–a movement that’s built on the work of many before him but that’s brought the issues of healthier eating and local organic farming into sharp focus across London and around the world.

The secret behind the success: Nutbourne farm and vineyard in West Sussex. Besides providing seasonal produce and meat for the Gladwin brothers’ restaurants, Nutbourne was where they were raised. Growing up on the farm clearly gave them an appreciation for the rich palette of seasonal flavors (both domesticated and wild) that now serve as the foundation of many of the dishes found in both restaurants–not to mention an approach to cooking that encourages the sustainable and creative maximization of whatever’s on hand.

With the eldest brother Oliver as the head chef, Richard the business manager, and the youngest brother Gregory the farm manager, Rabbit’s cuisine is the product of a loose and cooperative division of labor that lets each brother focus on their area of expertise while allowing inspiration for finding new ways to express the flavors of the English countryside on Rabbit’s constantly changing menu to come from anywhere: a sudden garden bounty, a kitchen discovery, a farmers market foray, a lucky wild foraging find, a hunting trip, a conversation with a fellow chef, or perhaps even an idea from a customer.

At the top of the menu is the only listed beverage: the daily loosener, which on my visit was the Apple Bite cocktail. Served in a kitschy boot-shaped glass and made from gin, apple, vanilla, star anise and soda, the concoction was refreshing in every way, appropriately loosening me up after hours of traipsing around the city and sufficiently opening my mind with intriguing hints of exotic flavors to get me primed for the parade of delights that was to come.

The beetroot crisp was a foamy little dream of a thing tucked into a cloud of whipped goat cheese and quince jam that passed by my taste buds like a summer breeze. More substantial but no less ephemeral was the cod rillette, served cold and chopped with lemon on a caraway crisp. Its mild fishiness was offset with the bright lemon, a sprig of dill, and some kind of light cream that bound it all together just long enough to get into my mouth before dissolving into nothing but memory.

Bringing this warm-up round to a close was a morsel of moist rabbit confit filled with savory poppy seeds (that must have been pickled–because they popped like caviar when chewed) and served with the lingering kiss of a tarragon sprig. I barely had time to savor this playful and artfully textural amuse-bouche before I was presented with what would be one of the best parts of the night.

Cures (for cured meats and veggies) occupy a whole section of the Rabbit menu and the first one I was served, the gin-cured trout, showed why. Served with pickled carrots, horseradish curd, and rapeseeds that deftly cut through the fat and salty trout flavors, this fish was a jaw-dropping revelation. The meat was pink, moist, thick: redolent of both Scandinavian and Japanese cooking and altogether satisfying in an almost primal way. The dish paired extremely well with the crisp house white wine (made at Nutbourne). Not ordering more required extreme self restraint.

It was becoming apparent that there was constant communication between the floor staff and kitchen because, again, almost as soon as the last bit of chorizo was swallowed, the first of my fast cooked plates arrived: a fried paprika cuttlefish served with black bean paste, almonds, sweet chili sauce, and topped with red-vein sorrel microgreens. While I was impressed with the commitment to timing, the dish wasn’t my favorite. The cuttlefish was lightly breaded, and the bean paste was a nice, if a bit overpowered, complement to the lightly fried fish but the very simple and strong sweet chili sauce sent the whole dish careening straight into a fairly routine Asian flavor territory. It struck a slightly off-key note for a meal filled with otherwise unique flavor combinations.

The slow-cooked braised venison blade served with pici pasta (similar to fat spaghetti), tarragon, and sourdough bread crumbs was an absolute marvel. Stewed in some kind of simple tomato and broth base with an infused herbal oil, the meat was gelatinous and shredded like you’d expect from a game animal like wild boar, but with a hearty richness and a savory sweetness that elevated it leagues beyond typical venison, oxtail, or even southern pork BBQ (its closest analogues). So profound was the satisfaction the dish commanded that I could scarcely utter a coherent word until this mighty main course was no more.

Upon inquiry, it turned out that the venison was wild and had actually been harvested by Gregory at Nutbourne for the unpardonable crime of eating his crops. So, not only was the meat local, fresh, and hand-butchered, but, up until quite recently, it had been eating a diet of some of England’s most valuable organic produce. No wonder it was so good. What’s more, it was garnished with wild-foraged nasturtium greens the brothers had recently brought in from some wild corner of Sussex. The dish was a true taste of the land and provided a great example of a Gladwin cooking maxim: what grows together goes together.

After this decadence, there was simply no room for dessert beyond a dip into the calm, lapping waters of a sweet Sauterne to help ease me back to my normal reality from this too-brief glimpse of the playful decadence possible in a rural English kitchen.

In my experience, I’ve never come across a better example than Rabbit of how farm-to-table food can work in the service of elegant and adventurous fine-dining, and I must say I was a bit surprised. The hoary cliché still common in the U.S., that British cuisine is bland at best with simple dishes like Shepherd’s Pie and Bangers and Mash, is in need of a complete overhaul. Rabbit is a sure sign that farm-to-table has arrived in London and that there’s no shortage of ideas and flavors on the Isles to be explored in creative and delicious ways. The Gladwins (named young entrepreneurs of the week by Huffington Post UK) show that when approached with a commitment to freshness and originality, eating local can be an exquisite joy. The brothers’ highly praised The Shed: The Cookbook may provide a way for distant Americans to savor their inspirational cuisine.

[Rabbit, 172 Kings Road, Chelsea, SW3 (near Sloane Square Tube Station), +44 20 3750 0172, Lunch & Dinner: Tues-Sat Noon-Midnight, Dinner: Mon 6:00PM-11:00PM, Lunch: Sun Noon-4:00PM]

(Matt Bierce, 12/3/15)

[Editor’s Note (FWB): The dining directories on this website for England, Scotland, Wales (and Ireland too) confirm that the good food movement is a growing force in Britain (and Ireland). Credit should be given to diverse factors including the long history of community gardens in England (the inspirational story of the transformation of Todmorden in West Yorkshire into a community growing its own food deserves special attention) to the advocacy of Prince Charles to take care of the earth that sustains us, exemplified by his remarkable speech, On the Future of Food (Rodale, New York, NY 2012), which in its published format by Rodale books has a foreword by America’s inspirational Wendell Berry and an afterword by Milwaukee’s urban agriculture pioneer Will Allen and investigative journalist Eric Schlosser. In Prince Charles’ s words: Only by working within Nature’s system, can we hope to have a resilient form of food production and ensure food security in the long term.]