Archive for January 2015

Organic Farming’s Transformative Power: The Dirty Life by Kristin Kimball

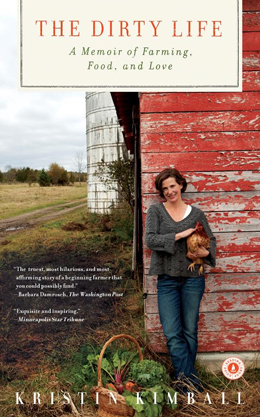

The Dirty Life: A Memoir of Farming, Food, and Love by Kristin Kimball (Scribner, New York, New York, 2011).

The Dirty Life is Kristin Kimball’s story of discovering the two loves of her life – the love for her future husband, Mark, who she meets while on a journalism assignment, and the love for organic farming, which she unearthed as the couple began to farm together in Essex County in upstate New York. It’s not an easy life, but it’s one that calls to the deepest parts of them.

Before meeting Mark, Kimball lived in New York City, working as a freelance writer. Farming plunged her into a different world: “Instead of the lights and sounds of the city, I’m surrounded by five hundred acres that are blanketed tonight in mist and clouds, and this farm is a whole world darker and quieter, more beautiful and more brutal than I could have imagined the country to be.”

Driven by Mark’s idealism and determination, the couple develops a plan to offer a full-diet, year-round CSA, providing not just vegetables, but eggs, grains and flours, herbs, maple syrup, meat – beef, pork and chicken — and dairy for their subscribers.

They eschew the use of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers, feed their cows grass and milk them by hand. One interesting passage describes the different flavors milk can have, depending on what the dairy cows’ diet was made up of. It reminded me of Barbara Kingsolver’s description of the difference between store-bought tomatoes and locally-grown tomatoes in her book, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

“Milk, like wine, has a serious gout de terroir [taste of the earth],” Kimball writes, “characteristics inextricable from the environment in which it is produced. Most commercial milk comes from cows that never step hoof on pasture while they are lactating. Instead of grass they eat what’s called a TMR – a total mixed ration. It is carefully calibrated to maximize milk production while minimizing cost and might consist of haylage or silage – chopped, preserved fodder – ground with protein boosters like soy or the malted grain left over from brewing. If you think of milk as a commodity, one squirt pretty much the same as any other, then the TMR makes perfect sense. But if you begin to think of milk as a food with seasonal and regional character, the TMR begins to seem as crazy as making wine out of hydroponic grapes.”

[Editor’s note: Similarly, Rowan Jacobsen in his American Terroir describes the unique taste of extraordinary Vermont maple syrup produced by Paul Limberty’s Happy Hollow, a one-man operation in Huntington (Chittenden County), Vermont. Happy Hollow has 2000 taps in its maple grove, which constitutes “one of the highest sugar bushes in the world at 2100 feet.” Mr. Limberty tastes every single barrel of syrup that comes off the wood-fired evaporator, jots down a few tasting notes in his log, and when he hits a batch especially excellent it becomes his certified organic Private Reserve line. In Mr. Jacobsen’s eloquent words, a bottle of this maple syrup, called Dragonfly Sugarworks’ Private Reserve, “contains the essence of the life force of a single day in a high mountain maple grove.” (FWB)]

As much as the book is about farming – the process and hard work of growing food – it’s also about the food itself. The book is peppered with descriptions of sumptuous meals made with organic ingredients: kale with poached eggs, deer liver with homemade bread and a fresh salad, icefish chowder, dandelion greens in winter, the first Thanksgiving dinner Mark makes for Kristin’s family.

“For Mark,” Kimball writes,” food is an expression of love – love of life, and love for the people around him – all the way from seed to table. I think my family could taste how deep his love ran, and between the squash pie and another glass of wine, they decided – even as he talked freely about his desire to live in a money-free economy, in a house without nails – that it was possible, just possible, that I had not come completely unhinged.”

Kimball’s story is also about the transformative power of the land. She goes from a somewhat fit 30-something writer to a gritty farmer, scraping by financially, learning to make butter and cheese, raise, feed and slaughter animals, drive draft horses, and fix things around the farm. Like her relationship with Mark, the journey is not always smooth, but it is (eventually) vastly rewarding.

“As much as you transform the land by farming, farming transforms you,” Kimball writes. “It seeps into your skin along with the dirt that abides permanently in the creases of your thickened hands, the beds of your nails. It asks so much of your body that if you’re not careful it can wreck you as surely as any vice by the time you’re fifty, when you wake up and find yourself with ruined knees and dysfunctional shoulders, deaf from the constant clank and rattle of your machinery, and broke to boot. But farming takes root in you and crowds out other endeavors, makes them seem paltry. Your acres become a world. … A farm asks, and if you don’t give enough, the primordial forces of death and wildness will overrun you. So naturally you give, and then you give some more, and then you give to the point of breaking, and then and only then it gives back, so bountifully it overfills not only your root cellar but also that parched and weedy little patch we call the soul.”

Spoiler alert: The Essex Farm is still in business. At the time the book was written, Kimball and her husband fed 100 people. Today, according to Kimball’s website, they have 222 subscribers and the farm has grown to 600 acres. They have 15 solar panels, nine draft horses, 10 full-time farmers and three tractors. In 2014, the membership cost $3700 per year for the first adult, $3300 for the second adult, with a $400 discount for each additional adult. Children over 3 are $120 per year of age. Every member of a household must be a member.

You can read more about Kristin Kimball and the Essex Farm at www.kristinkimball.com/.

(Gillian Scott, 1/09/15)

[Editor’s Note: The full-diet, year-round CSA offered by Essex Farm is an affordable way for a consumer to have an organic diet and provides a convincing basis to counter the complaint that organic is too expensive, which is stressed over and over by policy makers backed by industrial food producers as a defense of “no holds-bar” commodity agriculture. The cost of approximately $70 each week for the Essex Farm (full-diet, year round) high-quality foods suggests that the $20 billion the United States now provides in agricultural subsidies could be much better spent to subsidize shares in CSA farms. Further, as a closing note, a profile of Ms. Kimball, An Unexpected Farmer, by Christine S. An, published in Harvard Magazine (October, 2010), quoting Kimball’s words that she has unexpectedly discovered “an awfully good way to live” demonstrates the praiseworthy values of Drew Gilpin Faust, the current President of Harvard University, who, in a letter to the New York Times (Feb. 15, 2013), wrote:

“When I speak with students today, I encourage them to pursue those interests that enable them to make their particular contribution to the world. A graduate working to begin a start-up or one pursuing a career in the creative arts [and might I add- a hard-working farmer who cares about the long-term health of her land and the people she feeds] would likely not score high on the proposed federal scale of educational worth. Nor would the nearly 20 percent of our graduates who each year apply to Teach for America . . . . Equating the value of education with the size of a first paycheck badly distorts broader principles and commitments essential to our society and our future.” (FWB)]

No Processed Foods for 100 Days: A Doable New Year’s Resolution

Four years ago (back in 2010), Lisa Leake and her family of four went 100 days without processed food on a small budget. That experience led to her creation of a very popular blog and a bestselling book, 100 Days of Real Food: How We Did It, What We Learned, and 100 Easy, Wholesome Recipes Your Family Will Love. Leake’s blog provides support, motivation and recipes for anyone who adopts the very doable New Year’s resolution of no processed foods for 100 days. And if this resolution seems too challenging, guidance to meet a ten day pledge of no processed foods is available on Lisa Leake’s blog and can be the basis of a very manageable New Year’s resolution.

Defining the meaning of “real food,” as distinct from “processed foods,” is at the heart of Michael Pollan’s Food Rules, a book worth studying. Lisa Leake further simplifies Pollan’s rules, with her suggested plan of action. Her summary of “the exact rules we followed during our 2010 pledge” of no processed foods for 100 days consisted of these seven basic rules: (1) No refined grains, only 100% whole grain; (2) No refined or artificial sweeteners, only honey and pure maple syrup; (3) Nothing out of package that contains more than five ingredients, (4) No factory-farmed meat, only locally raised meat products; (5) No deep-fried foods; (6) No fast food; (7) Beverages only to include water, milk, occasional all-nautral juices, coffee and tea, and wine and beer in moderation.

Acres U.S.A. magazine recently reported (November 2014 issue) on a new study published in the journal Obesity by Dr. John Sievenpiper of Toronto, Canada’s St. Michael’s Hospital’s Clinical Nutrition and Risk Factor Modification Centre which found that “eating about one serving a day of beans, peas, chickpeas or lentils (pulses) can increase fullness, which may lead to better weight management and weight loss.” These unprocessed (or whole foods) are metabolized (or break down) slowly, with their low glycemic index. Excellent sources of protein, they can be incorporated easily into a diet that leads to the successful completion of the resolution to avoid processed foods for 100 days. (This website has recipes for delicious bean burgers as well as a simple recipe for hummus (made from chickpeas) which are tasty ways to include pulses in a whole foods diet.)

Support for Lisa Leake’s basic rule to avoid artificial sweeteners has also gained recent support from the findings of a study by Dr. Eran Elinav, an immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and his collaborators, which was recently published in Nature, the international weekly journal of science. According to an article in the New York Times on September 18, 2014 by Kenneth Chang, Artificial Sweeteners Alter Metabolism, Study Finds, “Artificial sweeteners may disrupt the body’s ability to regulate blood sugar, causing metabolic changes that can be a precursor to diabetes.”

Another very doable New Year’s resolution, which fine tunes a commitment to avoid processed food, is to join a community supported agriculture farm (CSA farm). In addition to avoiding processed foods, a shareholder in a CSA commits to eating with the seasons and becomes a part of a small community that supports a particular farm family. In the modern world’s conundrum of hubbub and the loneliness of disconnection, membership in a CSA farm leads to a whole foods diet as well as knowing where and how your food is grown and the valuable feeling of connection to the land on which your food is grown. This website takes pride in maintaining directories of CSAs throughout the United States and Canada.

And for those who already have a share in a CSA, a resolution to control the daily intake of sugar is a very fine resolution given momentum by the hard hitting documentary film, Fed Up narrated by Katie Couric. As a personal note, I’ve been conscious of keeping sugar consumption on a daily basis below 50 grams and it has resulted in better health and some weight loss. The current draft guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) point out that sugars should make up less than 10% of total energy intake (calories consumed) per day, which is equivalent to less than 50 grams (approximately 12 teaspoons) of sugar per day for an adult of normal Body Mass Index.

Both Michael Pollan and the film Fed Up share the view that consumption of sugar, in all its forms, is not healthy. However, according to a recent study carried out at Harvard Medical School, as reported in the article, Vulnerability to Fructose Varies, Health Study Finds by Anahad O’Connor in the New York Times (10/14/14), the consumption of high fructose corn syrup “may promote obesity and diabetes by overstimulating a hormone that helps to regulate fat accumulation” and appears to be in an unhealthy league of its own. In contrast, Pollan in his Food Rules puts all types of sugar into the same “avoidance” category . In any event, Rule 4 of his Food Rules, “Avoid food products that contain high-fructose corn syrup,” remains critical. [Pollan’s basis for this rule was “not because high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is any worse for you than sugar, but because it is, like many of the other unfamiliar ingredients in packaged foods, a reliable marker for a food product that has been highly processed . . . [and] it is being added to hundreds of foods that have not traditionally been sweetened.”] Finally, Pollan’s Rule 5, “Avoid foods that have some form of sugar (or sweetener) listed among the top three ingredients,” which closely complements Rule 4, is still of upmost importance in our age of highly processed industrial food when there “are now some forty types of sugar used in processed food, including barley malt, beet sugar, brown rice syrup, cane juice, corn sweetener, dextrin, dextrose, fructo-oligosaccharides, fruit juice concentrate, glucose, sucrose, invert sugar, polydextrose, sucrose, turbinado sugar, and so on.”

Best wishes for a happy and healthy New Year.

(Frank W. Barrie, 1/1/15)