Archive for July 2014

“Historic” Marker Outside Farm-to-Table Restaurant Uses Humor to Make Its Point

Sharon Springs (a small village with a population of 547 at the 2000 census) in upstate New York’s rural Schoharie County is the home of a terrific farm-to-table restaurant, 204 Main Bar & Bistro. As starters, my dining companions shared pot stickers ($8.00), local pork and shrimp, house made noodles, Asian slaw, spicy soy dipping sauce, which a dining companion said was “better than what you get in NYC’s Chinatown,” and of course the ingredients were of first-rate quality at this wonderful bistro. I enjoyed a beet and goat cheese salad ($7.00), perfectly balanced with roasted beets, goat cheese chèvre, walnuts over mixed salad greens and lightly dressed with orange soy vinaigrette. After satisfying entreés of pan-roasted chicken ($19.00) in a delicious lemon butter sauce, with sides of potato pavé (a scalloped potato dish) and asparagus, and perfectly prepared pork schnitzel ($19.00), breaded and pan fried, served over mixed greens and topped with a fried egg (the choice of each of my three dining companions), we decided to share a dessert. A perfectly prepared lemon semifreddo ($7.00), a frozen mousse made with egg yolks and heavy whipping cream topped with blackberries and raspberries, was a wise choice for sharing given its extraordinary richness.

Appetites tamed, as we left the bistro, we were stopped in our tracks after noticing the “historic” marker outside 204 Main Bar & Bistro. With humor, the marker confirmed our decision to dine in this wonderful Sharon Springs bistro that features food sourced locally and grown with care. The humorous “historical” marker was the perfect touch to lift the spirits after a delicious meal.

An easy half-hour drive from Cooperstown, the famous home of the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Glimmerglass Opera (which this summer is staging a powerful production of Madame Butterfly among other rich programming), Sharon Springs is beckoning visitors with its terrific farm to table dining, and a visitor can see and feel the signs of renewal. And with the village’s own special festivals, it’s becoming a destination in its own right: the Garden Party Festival in May, Father’s Day Tractor and Antique Power Show in June, the Wee Wheels Tiny Car Show in August, the Harvest Festival in September, and the Victorian Festival in December.

[204 Main Bar & Bistro, 204 Main Street, Sharon Springs (Schoharie County), NY, 518.284.2540, Lunch: Daily (but closed Tuesdays) 11:30AM-2:30PM, Dinner: Daily (but closed Tuesdays) 5:00PM-10:00PM http://204mainbistro.com]

(Frank Barrie 7/14/14)

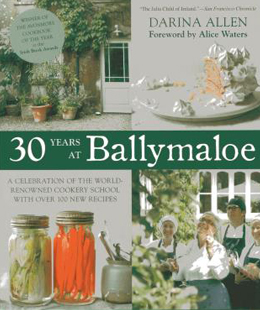

More Than A Superb Cookbook: Darina Allen’s 30 Years at Ballymaloe

30 Years at Ballymaloe, by Darina Allen (Kyle Books, London, UK, 2014, Distributed by National Book Network, Lanham, MD). This beautiful book is not so much a cookbook (although it contains over 100 recipes) but more the story of a journey. From a culinary wilderness to the heights of excellence, a family’s journey fueled by a commitment to local food, handcrafted produce and sustainable practices.

30 Years at Ballymaloe, by Darina Allen (Kyle Books, London, UK, 2014, Distributed by National Book Network, Lanham, MD). This beautiful book is not so much a cookbook (although it contains over 100 recipes) but more the story of a journey. From a culinary wilderness to the heights of excellence, a family’s journey fueled by a commitment to local food, handcrafted produce and sustainable practices.

In 21st century Ireland, the Allen family is synonymous with quality food and inspired cooking. In the early 1960s, however, the country still languished in a state of post-war blandness. Long imposed frugality had generally blunted the sense of food as a source of imagination. Additionally, as noted by famed chef and co-chair of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, Claudia Roden (a contributor to the book), in those days going out to a restaurant was a rare event reserved for special occasions such as birthdays. Against that unpromising backdrop, Myrtle Allen opened a small restaurant in her rambling old farmhouse in County Cork. As a cook she was completely self-taught. As a restauranteur she had no experience whatsoever. But Myrtle Allen knew the value of good ingredients and recognized that in the lovely country of East Cork she was blessed by bounty: freshly caught fish from the nearby sea, an abundance of vegetables, free range poultry and grass fed cattle, as well as local artisans skilled in the old ways of food preparation and preservation. As Myrtle’s restaurant gained traction, she extended her culinary repertoire through courses at Le Cordon Bleu in London and L’Ecole des Trois Gourmands, co-founded by Julia Child during the 1950s in Paris. In time, the restaurant became so successful that she and her husband decided to branch out into providing accommodation. And so the legendary Ballymaloe House Hotel was born.

Darina Allen, the author of this book, arrived at Ballymaloe House Hotel in 1968 as a student. She came to work in the Balllymaloe kitchen in the hope of learning some of Myrtle Allen’s skills. Coming from the industrial-style kitchens of hotel and hospitality school, Ballymaloe was an eye-opener for Darina. Unlike menus of so many restaurants of that time that stuck to the familiar and rarely changed, the menu at Ballymaloe was re-invented each day depending on what was in season and available on the farm and in the garden. The food was made from scratch: ice cream from fresh milk and cream, baby beef and pork provided by calves and pigs in the farmyard, freshly laid eggs came from the hens that were fed with scraps from the restaurant. Local children foraged for blackberries, damson plums and mushrooms and brought them to the kitchen door where Myrtle paid them generously. In 1968 Myrtle began giving cooking classes and she asked Darina to assist. In 1970 Darina became a member of the family by, as she says, the simple expedient of marrying Myrtle’s son, Tim.

By 1983, having absorbed the Allen philosophy and become an accomplished chef and teacher in her own right, Darina launched a residential cooking school, the Ballymaloe Cookery School, with her brother, Rory O’Connell. Since its founding the school has gone from strength to strength, growing from an initial six-week course to courses throughout the year, as well as shorter specialized courses, that attract students from all over the world. Darina and Ballymaloe have been in the forefront of creating a new Irish culinary confidence that owes much to Myrtle Allen’s belief that quality fresh, naturally produced local food provides superb fare that is not dependent on elaborate embellishment for flavor. Darina has taken a leading role in establishing the Slow Food movement in Ireland, setting up the East Cork Slow Food Convivium at Ballymaloe which has now grown to over 100 members. Not limited in imagination, in 2013 she launched the Ballymaloe Literary Festival of Food and Wine, featuring authors, chefs, foragers, wine experts, gardeners, publishers and bloggers, among others. It was a huge success and In 2014 the festival attracted some high caliber talent: among many eye-catching offerings was a dinner cooked by Yotam Ottolenghi and a foraging workshop by Rene Redzepi of Copenhagen’s famed Noma restaurant.

The Allen culinary dynasty now extends to a third generation. Darina’s daughter-in-law, Rachel, is also an accomplished chef, teacher and cookbook author.

In 30 Years at Ballymaloe, Darina chronicles the saga, from Myrtle Allen’s gutsy move to open her restaurant in 1963 through 2013, with Ballymaloe established as an internationally acclaimed cookery school. Proof of the latter is attested to by Alice Waters in her foreword to the book and by contributions from luminaries such as Madhur Jaffrey and the late Marcella Hazan, who gave classes at the school at various times. In a wide range of chapters, a variety of issues are explored and experiences recounted. There are features on keeping cows, pigs and hens, food allergies, going organic, canning, sustainable fishing, self-sufficiency, butchery and starting a fruit orchard. The orchard at Ballymaloe is an example of the Allens’ dual commitment to heritage and the provision of fresh produce: it contains an impressive range of fruits (all nourished by farmyard manure, seaweed and compost) including numerous berries such as loganberries, gooseberries, boysenberries and multi-colored currants. Several fruits have been selected for cultivation in an effort to preserve and reacquaint people with their almost forgotten flavors as they are no longer easy to obtain in shops and supermarkets.

Chapters on the creation of the Ballymaloe herb garden and on foraging are in themselves worth the price of the book. Darina is unafraid, however, to acknowledge occasional setbacks: she recounts an unsuccessful attempt to create a living maze and concedes that nature has a way of thwarting even the best structured plans. The Allens were inspired by traditional mazes of yew and started with the purchase of several thousand small yews that unfortunately failed to thrive, grew sickly and eventually had to be removed and replaced: proving that you can’t take for granted a happy marriage between a plant and its host soil. Fortunately, the beech and hornbeam that replaced the yew made themselves at home and 20 years later Ballymaloe has a wonderful Celtic maze, inspired by an illustration from the 9th century Book of Kells.

The author provides insights about such things as kitchen equipment (she prefers Le Pentole ICM saucepans and almost anything from E. Dehillerin in Paris) to more arcane matters, like the breed of cattle best suited to provide delicious milk (Jersey), to provide meat (Kerry) and best of all, meeting a dual purpose, to thrive even on marginal soil (Kerry again). She advocates for raw milk because of its suggested anti-allergic properties and supports the spirited campaign to oppose a ban on raw milk proposed by the Irish government. It is clear that Darina Allen is no fan of mindless regulation, particularly emanating from the European Union. She notes that the imposition of increasingly rigid regulations in many areas of traditional food production are upping the cost and driving small family enterprises out of business. This is a battle for the hearts and minds that has yet to be resolved.

Then there are the recipes. They cover a wide range such as gluten free raspberry muffins, pork belly with olive tapenade, wild garlic custard, deep fried squid with aioli and tomato/chili jam and chocolate and caramel mousse. Some are exotic and complex, others alluring in their simplicity. All have in common their primary reliance on fresh ingredients.

The book’s text is complemented by numerous wonderful photos by Laura Edwards. Fields, gardens, cows, hens, fruits, country markets, flowers, kitchen, finished dishes: together they provide a sumptuous palate. Photos of freshly dug pink potatoes nestling in a wicker basket, an array of colored mushrooms ready for the pan, or the wonderful colors of a herbaceous border eloquently illustrate the balanced natural harmony that underlies the Allen philosophy. Photos and text together make a book that is both lovely to look at and an absorbing read. 30 Years at Ballymaloe is a book one can learn from but, above all, enjoy.

(Eidin Beirne 7/10/14)

From One NYC CSA in 1995 to 100+ Today

The Big Apple now boasts more than 100 CSA programs according to the local food advocacy group Just Food which promotes CSAs, farmers markets and other urban food initiatives (including its inspirational City Farms program). Just Food estimates that nearly 40,000 Gothamites now get their produce through Just Food-affiliated CSAs. Considering there was only one CSA in NYC in 1995, this growth, in arguably the best way for consumers to know where their food comes from (other than growing it themselves), is a deeply satisfying sign of hope in our modern era of edible food products produced by industrial operations, whose bottom line of profit-making dominates their decision making.

CSAs benefit consumers, who can obtain healthy, fresh, good food, in a way that directly connects them to the source of their food. Farmers who adopt this model of small scale, non-industrial agriculture also benefit because consumers jointly share the risk and costs of farming by paying for their food shares upfront, and they can focus on producing food during the growing season rather than spending time finding a market for what they grow.

With the increasing number of CSA farms and other sources of good food (including the more than 60 farmers markets throughout the five NYC boroughs operated by Greenmarket), some established CSA farms have been slower to sell-out their shares or have witnessed a slight decrease in shareholders. The granddaddy of CSA farms in upstate New York, biodynamic Roxbury Farm, a 300-acre farm in Kinderhook (Columbia County) is short 15 members this season; but with over 1000 shareholders representing over 1200 families, this minor shortfall represents only $9,000 of an $800,000 budget. Still, in past years, shares at pickup locations in the Capital Region, for example, were sold out in January, months before the start of the growing season. Roxbury Farm’s shareholders reside in Columbia County, the Capital Region, Westchester and Manhattan, and if you’re considering participating in a CSA this growing season and live in one of these areas, perhaps one of these 15 shares might still be available as of the date of this post.

Garden of Eve Farm on the East End of Long Island in Riverhead (Suffolk County) has also seen a marginal decline in new members from its peak of around 900 shareholders. Eve Kaplan-Walbrecht, co-founder with her husband, Chris Kaplan-Walbrecht, of this organic Long Island farm, suggests to make up any decline in shareholders, farms might downsize, try specializing to meet niche demand, try partnering with different farmers to offer more products in their CSAs or perhaps even operate a farm café. Garden of Eve Farm runs a farm café on its farm which offers “lunch items from deli case daily” from April to Halloween as well as hot food entrees on Wednesdays through Sundays.

The Wassaic Community Farm in Wassaic (Dutchess County) was established in 2008 with a mission to address food justice issues both locally in Dutchess County where the farm is located and in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Besides delivering some of its CSA shares for pickup at the farm and another location in Dutchess County, it delivers CSA shares to a location in the Bronx and at the Bushwick Farmers Market in Brooklyn, where it also operates a farmstand on Saturdays from 11:00AM-4:00PM.

In New York City, there has been the development of a “distributor/CSA hybrid” called Next Doorganics, which originally started in 2011 as a traditional small CSA. According to Next Doororganics founder Josh Cook, “People want to support farms but they want it to fit with their lifestyles.” Based in Brooklyn, Next Doororganics now sells weekly shares sourced from a variety of local New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania organic farms (and even some urban rooftop farms) year-round. Winter share boxes also include food from small organic farms in California according to Cook. In upstate New York, Farmie Market, representing nearly 90 farms throughout the Capital Region, Mohawk Valley and Hudson Valley, offers customers in its service region the option to order food on-line from “small, environmentally and socially-responsible farms.” And in Western Massachusetts, Berkshire Organics, working with over 50 local farms and businesses, “Brings the farmer’s market to your door” by offering produce baskets or individual items (totaling at least $35) for delivery throughout Berkshire County or pickup of at the store located in Dalton (Berkshire County) with everything “certified organic or locally, sustainably produced.”

While convenient, there’s a price to these alternative distributor arrangements compared to a traditional CSA farm model. Garden of Eve Farm co-founder Eve Kaplan-Walbrecht puts it precisely: “People don’t have a relationship with the farm and can’t come out and understand exactly where their food is from.”

(Matt Bierce 7/7/14)