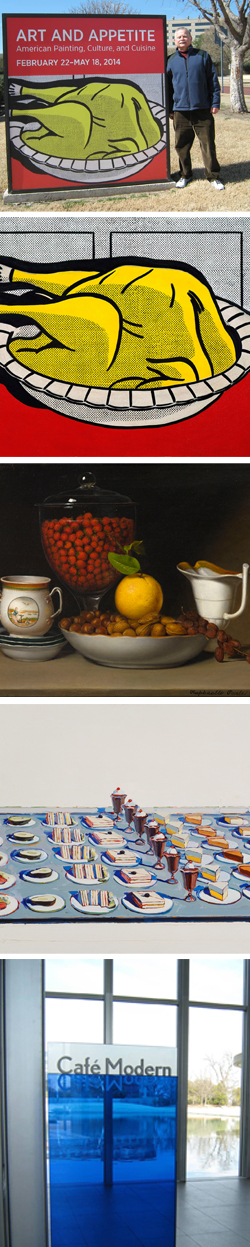

Nine years ago in 2005, curators at the Art Institute of Chicago including Judith A. Barter, the Art Institute’s Curator of American Art, first discussed “a fresh look at still-life painting through the food represented in the pictures.” This early beginning has culminated in an enthralling and major art show. With paintings on loan from more than 25 collections throughout the United States, Art and Appetite, American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine on display at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas through May 18, 2014 (after its earlier showing at the Art institute of Chicago this past winter), has a wide appeal that should interest aficionados of art exhibitions as well as people who rarely step foot in a museum.

Nine years ago in 2005, curators at the Art Institute of Chicago including Judith A. Barter, the Art Institute’s Curator of American Art, first discussed “a fresh look at still-life painting through the food represented in the pictures.” This early beginning has culminated in an enthralling and major art show. With paintings on loan from more than 25 collections throughout the United States, Art and Appetite, American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine on display at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas through May 18, 2014 (after its earlier showing at the Art institute of Chicago this past winter), has a wide appeal that should interest aficionados of art exhibitions as well as people who rarely step foot in a museum.

For those less inclined to visit an art museum, might I suggest heading first to see a painting (included among the approximately 70 painting on display) that should stimulate the brain of even the most blasé visitor. Of course, it might be difficult to pass hurriedly by the first grouping of paintings, focused on the American Thanksgiving, but more on that later.

Seek out and study the eye-opening painting, John Greenwood’s “Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam,” the oldest painting on exhibit, dating from before the American Revolution (1752) on loan from the Saint Louis Art Museum. This painting depicts drunken Rhode Island sea captains involved in the notorious triangular trade between New England, West Africa and the tropical Caribbean. Curator Barter’s essay, “Drunkards and Teetotalers: Alcohol and Still-Life Painting,” included in the beautiful catalog published in conjunction with the exhibit, Art and Appetite, American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine (The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 2013) points out the remarkable fact that in 18th century America, “the distillation of rum from molasses was the leading manufacturing process from Philadelphia northward.” Rum and goods would be traded for enslaved Africans, transported to the Caribbean to labor on sugar plantations. Sugar and molasses, in turn, would be transported from the Caribbean (including Surinam) to New England where it would be processed into rum.

Perhaps the most stimulating way to look at a painting is simply to ask, “What do I see?” and to repeatedly pose this same simple question. With this Where’s Waldo approach, Greenwood’s 18th century painting comes to life nearly 300 years after it was created. When the viewer finally notices the sea captain spewing his guts (in Hieronymous Bosch-like detail), the windmills of the mind will be spinning rapidly and the visit to an art museum for even a lackadaisical visitor will come alive. Then trace your steps back to the display of the four remarkable paintings at the entry way into the exhibit and to the synergy created by these four disparate art works that share a focus on the American Thanksgiving, described by curator Judith Barter in the accompanying catalog as the “greatest of all national food fests.”

Norman Rockwell’s Freedom From Want (1942), on loan from the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, painted at the height of World War II (and very familiar to me from earlier visits to to the Rockwell Museum not far from my home in Albany, New York), stopped me in my tracks in its new setting in Fort Worth. President Roosevelt’s State of the Union in 1941 identified four essential rights he considered universal: freedom of speech, freedom from fear, freedom of worship, and freedom from want. Rockwell painted these four freedoms and his “Thanksgiving Picture,” as pointed out by curator Barter, “made the turkey and its holiday a symbol of American values, freedom, and peace.” To view the Rockwell painting alongside Roy Lichtenstein’s cartoonish Turkey (1961), from a private collection, resembling an advertisement, Alice Neel’s Thanksgiving (1965), also from a private collection, with its modern overhead perspective of a kitchen sink where the turkey sits and drains, and Doris Lee’s joyful Thanksgiving (1935) from the Art Institute of Chicago depicting the energetic preparation of Thanksgiving dinner with the rolling of pie dough, checking the turkey roasting in the cast iron stove for doneness, and readying a variety of vegetables for cooking while toddlers seek attention, a cat scampers and a dog lays low near the hot oven, brought a new context and meaning for the famous Rockwell image.

The most represented artist in the exhibit, with six works on display, is Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825) who according to curator Judith Barter is considered to be “the first and among the finest American still-life painters.” His masterfully painted still-lifes rivaled the best European art of his time. Raphaelle Peale’s prominent Philadelphia family of artists and horticulturists maintained a family farm, Belfield. Its gardens and greenhouses provided Peale with inspiration for his painting. The Peale paintings on display are magnificent. They include on loan from the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, Peale’s Still Life with Steak (1817) which shows a fine piece of meat with winter vegetables of cabbage, carrots and beets; Melons and Morning Glories (1815), from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, depicting a juicy watermelon, a whole cantaloupe and blossoming morning glories; Corn and Cantaloupe (1813) from Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; Covered Peaches (1819) from the McNeil Americana Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and arguably the show stopper, Still Life-Strawberries, Nuts, &c. (1822) from the Art Institute of Chicago, with its impressive depiction of strawberries soon to be eaten with sugar and cream, hazelnuts and almonds, an orange, and grapes becoming raisins along with a sugar bowl and creamer (Chinese export porcelain) and a large glass urn containing the strawberries. The curators note in the exhibition catalogue that “The incorporation of material culture into the still-life composition also hints at political divisions within the young Republic between Jeffersonian agricultural interests in the South and mercantile priorities in the north.”

A must-see exhibition, Art and Appetite examines 250 years of American art, from the agricultural bounty of the “new world” to Victorian-era excess, debates over temperance, the rise of restaurants and café culture, and the changes wrought by 20th-century mass production. A minor quibble is that the show includes only three living artists, Richard Estes, Wayne Thiebaud and Claes Oldenburg, with the most recent work, Food City (1967) by Richard Estes from the collection of the Akron Art Museum. The photo realistic paintings of Richard Estes, including his well-known Food City on display in Fort Worth, are mesmerizing. Coincidentally, for those within visiting distance of Portland, Maine, a survey of the paintings of Richard Estes will be on display this summer at the Portland Museum of Art (May 22, 2014 through Sept. 7, 2014) co-organized by the Maine museum and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

A final note, the Café Modern located at Fort Worth’s Modern Art Museum, a five-minute walk down the hill from the Amon Carter Museum, offers a wonderful lunch menu with an emphasis on local farm to table ingredients in a stylish modern setting. [Café Modern at Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell Street, 817.738.9215, Lunch: Tues-Fri 11:00AM-2:30PM, Brunch: Sat-Sun 10:00AM-3:00PM, Dinner: Tues (during Lecture Series) & Fri 5:00PM-8:30PM, www.themodern.org/cafe.]

[The Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, Fort Worth, Texas, “Art and Appetite, American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine,” (until May 18, 2014; Open Tues, Weds, Fri, Sat 10:00AM-5:00PM, Thurs 10:00AM-8:00PM, Sun Noon-5:00PM)]

(Frank W. Barrie, 4/9/14)