Archive for November 2015

Pumpkin & Kale (or Spinach) Lasagna

Francesca’s Pumpkin & Kale (or Spinach) Lasagna

Francesca Zambello, the Artistic & General Director of The Glimmerglass Festival (in its 2016 season offering performances of Puccini’s La Boheme, Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie, Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd and Robert Ward’s Crucible, based on Arthur Miller’s dramatization of the Salem Witch Trials) in Cooperstown (Otsego County, NY) has shared a favorite lasagna recipe that grows out of her love for using local and seasonal vegetables. Her pumpkin and kale lasagna recipe is so delicious that it is a perfect option for vegetarians as a Thanksgiving entrée. Turkey lovers will also be tempted to enjoy a serving. With no tomatoes or mozzarella, its layers of sweet creamy ricotta, aged parmigiana reggiano, and puréed pumpkin upends the traditional tomato/mozzarella lasagna with subtle flavors of creamy sweetness and aromatic nuttiness from freshly grated nutmeg. Francesca notes that this lasagna freezes well and suggests making several trays to pull out for company. Served with a huge salad, it’s “always a hit.”

Sharing Francesca’s enthusiasm to use local foods, a Saturday morning visit to the year-round Troy Waterfront Farmers Market in Troy (Rensselaer County, NY) across the Hudson from my home in Albany was the source for local pumpkins to roast and purée for this recipe. (A friend who cooked up the recipe and admitted to using canned pumpkin, nonetheless received kudos from a fussy daughter who loved this comfort food.)

The Berry Patch Farm in Stephentown (Rensselaer County) was offering orange pie pumpkins as well as the beige squatty rumbo pumpkins. Relying on the advice of Berry Patch Farm’s Ila Riggs (a real benefit of shopping at a farmers market is getting to know the farmer who grows your food), I decided to use the rumbo pumpkins for the recipe. Although kale was available at the Troy market, the beautiful spinach available at the farmers market stand of Denison Farm, located in Schaghticoke (Rensselaer County), was too tempting for this spinach lover to pass by. Substituting spinach for kale made the lasagna resemble the flavors of a Greek spanakopita, which is similarly creamy, tangy, eggy and delicious. Fresh curly parsley with its deep green color from Slack Hollow Farm of Argyle in Washington County, NY (a popular vendor at the Troy market with its especially sought after NOFA-NY certified organic produce) added color, flavor and nutrition to this special lasagna.

Other ingredients from local sources, available at the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, included hand made whole milk ricotta cheese from Maplebrook Farm (just across the border from New York in Bennington, Vermont), “Meadow Butter” made from grass-fed cows from Kriemhild Dairy Farms located in Hamilton (Madison County, NY), the home of Colgate University, an alma mater shared by both Francesca and myself, and Oliver’s Organic Eggs in Frankfort (Herkimer County, NY). These “pastured, cage free, free range, non GMO, Soy Free and certified organic by NOFA-NY” eggs are well worth the $5.25 for a dozen. The co-op was also the source for Champlain Valley Milling’s whole wheat pastry flour (organic grains milled in Westport, Essex County, NY) and the tangy cultured milk (kefir) from Cowbella Dairy (Jefferson, Schoharie County, NY) used instead of milk.

High quality ingredients, not available from local farm sources, were also purchased at my local Albany, NY food co-op, including Bionaturae’s Organic Extra Virgin Olive Oil from first cold pressed 100% Italian olives. And after some discussion with Christine, a very helpful co-op cheese department worker, I opted for the raw milk Parmigiano Reggiano D.O.P. ($10.99/lb) “aged to perfection for two years in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy” instead of the less expensive parmigiano reggiano cheese from Argentina. Grating a little more than 1/2 pound of the cheese produced the needed two cups for the recipe. Christine shared a wonderful tip to save the cheese rinds, which could be frozen, and later used by adding to soups, especially tomato based, as they cooked.

The co-op’s remarkable Bulk Foods Department, with its hundreds of bins (where you can buy as much as you want or as little as you need), was the source for salt, pepper, pine nuts, whole nutmegs, and Foulds organic 100% whole wheat lasagna noodles (with its simple ingredients of organic whole durum flour and water). At $27.99 per pound, I was glad to have the option of purchasing only a half an ounce of Tierra Farm’s organic pine nuts for $1.12 in the bulk foods department. (Whether to substitute walnuts for pine nuts is an issue, and not only due to price, but also concern for preserving the remote pine forests of Siberia, Korea and northern China which are the source for pine nuts. According to a story by Dan Charles for National Public Radio, the pine nuts are hidden inside the cones of certain species of pine, such as the mighty Siberian pine, which covers thousands of square miles of Siberia.) I tend to use salt lightly in preparing food, and like to use the co-op’s coarse Himalayan Pink Salt available in bulk from Saltworks, which is “one of the purest found on earth having been protected by hardened java within the Himalayan salt beds for 250 million years.” Its beautiful pink color indicates a beneficial amount of trace elements and iron that occur naturally. I grind fresh, as needed in food preparation, organic black peppercorns from Mike’s Spice available in the co-op’s bulk foods.

Finally, special attention is properly paid to the nutmeg, since its warm sweet bite adds special flavor to this delicious lasagna. This was a first time experience (at my ripe old age) to grate fresh whole nutmeg. At $53.63/lb, the four or five nutmegs, also from Mike’s Spice like the peppercorns, cost $1.61 at the co-op, and they felt treasure-like as I grated half of one for the recipe. A lesson learned: using my inexpensive cheese grater was tricky and prompts me to purchase an actual nutmeg grater sooner than later. A fascinating side note: according to the nutmeg entry in Edible, An Illustrated Guide to the World’s Food Plants (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., 2008), there was an actual Peter Piper, famous for the tongue twister, Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled, yes, nutmeg. In history, Pierre Poivre (poivre is French for pepper, which in Latin is written as piper) broke the Dutch monopoly by smuggling nutmeg plants, Myristica fragrans, from the Moluccas (Spice Islands in Indonesia) to the then French island of Mauritius.

Francesca’s Pumpkin Lasagna Recipe (with some personal annotations in italics-FWB):

13-inch X 9-inch baking dish

(You can use the tin foil ones and put them in the freezer if you are making in bulk.)

Ingredients:

2 cups pumpkin puree

3 cups kale or spinach greens

3 Garlic cloves

1 pound of lasagna noodles

3 tablespoons all-purpose flour

2 cups milk

Freshly grated nutmeg

3 eggs

2 cups fresh ricotta

2 cups freshly grated Parmesan cheese

3 tablespoons butter

pine nuts (optional)

chicken stock (optional)

salt & pepper

olive oil

parsley (optional)

Pre-heat oven to 375 degrees

Bowl #1: Pumpkin

Start by chopping up your pumpkin and roasting it. Medium sized pumpkins are better than those huge ones! Roast it with a little olive oil or butter for about an hour at 350 degrees. (It took a long hour, close to 90 minutes, for me to roast the pieces of Rumbo pumpkin whose flesh was somewhat fibrous, and I basted very lightly every 20-25 minutes or so with olive oil to keep the pieces moist. FWB) Then cool it and scoop it out of the skin and mash it. (You can also do this and freeze a lot of mashed pumpkins to make bread or muffins later in the winter). Whisk together with 2 eggs and some salt and pepper and set aside in bowl.

Bowl #2: Greens

Sauté garlic in olive oil and then add kale or any of your greens.

Chop and keep to the side in a bowl. (I’ll admit to keeping the sautéed spinach, used instead of kale, in the large pan- avoiding another dirty bowl to wash- and without chopping, layering it directly on the puréed pumpkin-FWB)

Bowl #3: Sauce

Melt 3 tablespoons butter, add the flour and whisk for 1 minute.

Whisk in the milk (cultured milk known as kefir in my preparation-FWB) and the nutmeg. Cook until slightly thickened.

You can add stock here if you have it for more sauce if you wish.

Bowl #4: Cheese

In another bowl, whisk together ricotta, half the Parmigiano-Reggiano and the remaining egg.

Assembly:

• Spread a layer of lasagna sheets on the bottom of the pan

(I first cooked, for only 5 minutes in boiling water, and of course drained immediately, the organic 100% whole wheat lasagna noodles I used for the recipe, since they would later bake for an hour in a hot oven-FWB.)

• Then spread ½ the pumpkin mix on top of it

• Then spread the greens on top of the pumpkins

• Add second layer of lasagna sheets and then the other half of the pumpkin mixture. Spread most of the cheese mix over this pumpkin layer

• Pour most of the sauce over this layer

• Then make a top layer of lasagna sheets and spread with all of the remaining cheese mixture, followed by the last bit of sauce

• Top with remaining Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, pine nuts and parsley for color and any other loose bits!

Cover with foil and bake for 30 minutes, uncover and bake for 30 minutes more. Let rest for 10 minutes before cutting.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/20/15)

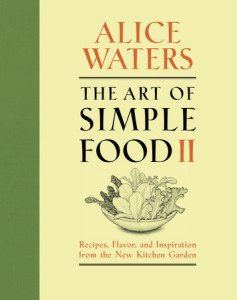

A Garden’s Simple Food Inspires Alice Waters’ Flavorful New Recipes

Alice Waters hardly needs any introduction. For decades she has championed the cause of the organic food movement, strongly believing it is better for the environment and people’s health. A proponent of a food economy that is “good, clean and fair,” she has been in the forefront of the Slow Food Movement and since 2002 has served as Vice President of Slow Food International. Her numerous books, the Chez Panisse Foundation (established by Waters in 1996 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of her Berkeley, California Chez Panisse Restaurant, the pioneer of farm to table dining) and which became the inspirational Edible Schoolyard Project in 2011, and vigorous public advocacy over 40+ years has earned Alice Waters recognition as an authority on the good food movement. Her most recent book carries on this praiseworthy life’s work.

Alice Waters hardly needs any introduction. For decades she has championed the cause of the organic food movement, strongly believing it is better for the environment and people’s health. A proponent of a food economy that is “good, clean and fair,” she has been in the forefront of the Slow Food Movement and since 2002 has served as Vice President of Slow Food International. Her numerous books, the Chez Panisse Foundation (established by Waters in 1996 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of her Berkeley, California Chez Panisse Restaurant, the pioneer of farm to table dining) and which became the inspirational Edible Schoolyard Project in 2011, and vigorous public advocacy over 40+ years has earned Alice Waters recognition as an authority on the good food movement. Her most recent book carries on this praiseworthy life’s work.

In The Art of Simple Food II (Clarkson/Potter, New York, 2013), Waters focuses on the rewards to be obtained from growing one’s own food. The book is subtitled Recipes, Flavor and Inspiration from the New Kitchen Garden and indeed is as much a paean to the satisfaction to be gained from growing one’s own food as to the pleasure of cooking it. Not only does fresh, organically grown produce taste better, but as any gardener will attest, there is also the deep satisfaction that comes from planting, nurturing and harvesting it oneself.

In a conversation with Leonard Lopate on his radio show produced by WNYC, Waters noted she felt a need to follow-up on her earlier book, The Art of Simple Food, Notes, Lessons And Recipes From A Delicious Revolution (Clarkson/Potter, New York, 2007) in order to focus on the need to take care of the land and “to ground” her latest book on real food (as opposed to fast, cheap and easy food) by treasuring the farmer and growers of food. She believes it to be necessary “that cooks be gardeners and gardeners be gastronomes” in order to ensure the integrity and sustainability of our food system. Thomas McNamee, in his biography of Waters, Alice Waters and Chez Panisse, The Romantic, Impractical, Often Eccentric, Ultimately Brilliant Making of a Food Revolution (The Penguin Press, New York , 2007), notes that Waters’ Chez Panisse, is as much a “standard-bearer for a system of moral values” as a restaurant: “It is the leader of a style of cooking, of a social movement, and of a comprehensive philosophy of doing good and living well.”

But the reader need not fear the prospect of being burdened with the responsibility of saving the planet: Waters delivers her message in an engagingly simple and down-to-earth way. Nor does she suggest that a large kitchen garden, brimming with a sumptuous array of vegetables and fruits, is required. Many of the vegetables, herbs and fruits that she writes about can be cultivated in small areas or in containers such as window boxes or planters.

True to the promise of simplicity inherent in the book’s title, Waters eschews complexity and instead relies on the satisfaction that she has obtained from fresh ingredients prepared in a straightforward way. It’s hard not to warm to a serious cookbook that salutes the grilled cheese sandwich and includes a hint to enliven it (add a couple of sage leaves). The book also contains many personal touches: Waters considers garlic such an essential ingredient that she carries with her a head of it whenever she travels! An account of her personal discovery of the lowly lettuce reveals the huge potential of so many varieties and makes you want to dash out and get hold of as many as possible.

Simple tips on growing abound, from the perfect time to plant turnips (early spring or late fall to ensure tender sweetness) to pinching back flower buds and bolting tips of leafy herbs such as basil and anise hyssop to prolong life and increase yield. Issues such as soil quality and enhancement, placement of particular plants relative to sun and shade, mulching, pruning and the timing of planting and harvesting are covered extensively. Nor are aesthetics ignored: there are notes on herbs or fruits that catch the eye in the garden due to their flowers or foliage (and those that attract butterflies) and suggestions for plant placements that complement each other.

And as one would expect from Alice Waters, the recipes are wonderful. There are nearly 200. They cover a full range of dishes from soups and salads, pickles and conserves, stews and roasts, to tarts, desserts and even liqueurs. They feature vegetables and fruits as mainstays as well as complements to meat, fish and fowl. None of the recipes are elaborate but, true to the promise of the book’s title, they epitomize the art of simple food.

The book contains a helpful “tools and resources” section that includes practical information about essential garden tools as well as seed catalogs, websites and newsletters. There is also a glossary of food labeling terms where the difference between terms such as “cage free” and “free range” is explained. Finally there is a glossary of gardening terms. The latter will be very useful for the new gardener.

The book is beautifully produced and contains numerous exquisite ink and charcoal drawings by Waters’ longtime collaborator, artist and printmaker Patricia Curtan. This informative and beautiful book would make a special gift for someone who is contemplating growing their own produce, or for someone already engaged in gardening. Or better still, treat yourself.

(Eidin Beirne, 11/17/15)

[Editor’s Note- Alice Waters wrote the foreword to (the accomplished Irish chef and teacher) Darina Allen’s 30 Years at Ballymaloe, which was previously reviewed on this website by Ms. Beirne. (FWB)]

Hard To Know Where Your Salmon Comes From

Fish counter at Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, NY

If the price is too good to be true, it probably is: $18.99/lb lends support that the fillet is truly wild caught King Salmon

Oceana, established in 2001 by a group of leading foundations (The Pew Charitable Trusts, Oak Foundation, Marisla Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund) to protect and restore the world’s oceans, has conducted “the largest salmon mislabeling study in the United States to-date.” The organization has reported that 43% of the 82 winter salmon samples its investigators tested were mislabeled. The most common form of mislabeling was farmed Atlantic salmon being sold as “wild salmon.” In addition, there were six instances in which supposed high-value chinook (also referred to as king salmon) was actually farmed Atlantic salmon, and one in which the cheaper chum salmon was sold as king salmon.

The mislabeling rates were more than three times higher in restaurants (67%) versus grocery stores (20%). Oceana’s report also notes that “salmon fraud” varied by region as well: with mislabeling highest in Virginia restaurants, where eight of nine samples collected (89%) were mislabeled; eight of 11 samples from Washington, D.C. restaurants were mislabeled; New York City had the lowest restaurant mislabeling rate, at 38% (but New York City had the highest grocery and market mislabeling, at 36%).

In an earlier 2013 national seafood fraud report, Oceana researchers found low rates (7%) of mislabled salmon. The organization suggests that the lower rate was likely “because the large majority of samples were collected at the peak of the 2012 salmon fishing season, when wild salmon was plentiful in the market.” Its recent report shows that mislabeling is much more common during the off-season (i.e., in the winter months).

Oceana’s recent report was based upon its study/investigation conducted during the winter of 2013-2014 in Chicago, New York City, Washington, D.C. and several locations in Virginia. Eighty-two samples from a variety of restaurants, large grocery stores and smaller markets were identified using DNA analysis at the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding in Guelph, Canada.

Oceana used a conservative interpretation of mislabeling for its analysis. The FDA’s Seafood List provides acceptable market names for seafood sold in the United States. In the case of salmon, acceptable market names for “wild salmon” (following the FDA principle of using “scientific common names for seafood”) would include coho, sockeye, chinook, pink or chum. However, the FDA’s Seafood List is only provided as “guidance” and according to Oceana “is often not followed when it comes to salmon.” Salmon is commonly sold as simply “wild” or “Pacific” salmon. If a sample labeled as wild, Pacific or Alaska, but with no species common name, was analyzed and determined to be “sockeye,” for example, Oceania’s investigators did not consider it mislabeled (even though a small amount of Pacific salmon is now being farmed).

According to Oceana, the United States “has some of the highest-quality salmon, caught by responsible fishermen, in some of the best-managed fisheries in the world.” Through its “fishermen catch,” the U.S. has “enough salmon to satisfy over 80 percent of our domestic demand.” (Salmon are caught commercially in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California and even Michigan (after being introduced to the Great Lakes), although Alaska catches 95 percent of the salmon in the U.S.) However, on average, 70 percent of that fishermen catch is exported instead of staying in the U.S.

Farmed salmon makes up an estimated two-thirds of the salmon consumed in the U.S. each year, and the vast majority is imported from Chile, Canada and Europe. Salmon farmed in Chile, and certain farms in Canada, Scotland and Norway that use “open-water net pens,” are rated as “avoid” by the Monterey Bay Aquarium [MBA] Seafood Watch due to their negative impact on the surrounding environment, the potential for disease transfer to wild populations, and the liberal use of antibiotic and pesticides. Further, according to MBA Seafood Watch, the feeds used on many farms can be highly inefficient, requiring between 1 and 3 pounds of wild fish to produce enough fish oil for 1 pound of farmed salmon.

Oceana’s report also notes that the U.S. exported more of our wild domestic salmon to China than to any other country, sending around 85,000 metric tons of wild-caught American salmon to be processed, with only 37,000 metric tons of what is presumed to be U.S. domestic salmon exported back to the U.S. However, Oceana notes that “A 2014 study estimated that up to 70 percent of the wild salmon exported to the U.S. via China is illegally caught Russian salmon.” Worrisome is the connection between “Russian salmon to organized crime, poaching and criminal environmental abuse in Russia, as well as corruption and tax evasion that extend to several trading partner countries in East Asia.”

Oceana proposes “that all seafood have catch documentation as a condition to market access.” The organization points out that if more Americans were aware of these issues, “we might see a purchasing shift toward the more sustainable, domestic salmon.” People need to know where their fish was caught or if it was farmed as well as its real name. Kudos to Oceana for these three common sense guidelines for consumers: (1) Seafood buyers should ask more questions, including what kind of fish it is, if it is wild-caught or farm-raised, and where and how it was caught; (2) Support traceable seafood since “Products that included additional information for consumers, like the type of salmon (chinook, king, coho, etc), were less likely to be mislabeled;” and (3) Check the price and if the price is too good to be true, it probably is.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/10/15)