Archive for July 2015

Dinner at Copenhagen’s Relae, Winner of the 2015 Sustainable Restaurant Award

Copenhagen’s Nørrebro, a neighborhood that is humorously labelled by Gawker as the Danish capital’s Williamsburg equivalent, is the home of Relæ, this year’s winner of the prestigious Sustainable Restaurant Award given by The World’s 50 Best Restaurants Academy. This academy is comprised of almost 1000 members, each selected for their “expert opinion” of the international restaurant scene.” To choose members, the world is divided up into 27 geographical regions with a chair person for each region, who in turn, selects a voting panel of 36 (including themselves). According to the website for The World’s 50 Best Restaurants, this “ensures a balanced selection of chefs, restaurateurs, food/restaurant journalist and gourmets.”

The Sustainable Restaurant Award is given to the restaurant on the The Worlds’s 50 Best Restaurants’ list “with the highest environmental and social responsibility rating, as ranked by audit partner, the Sustainable Restaurant Association (SRA).” Led by Copenhagen’s Relæ, the top five sustainable restaurants included one in the United States: Dan Barber’s Hudson Valley restaurant, Blue Hill at Stone Barns, in Pocantico Hills in northern Westchester County in third place. The World’s 50 Best Restaurants Academy gave the following explanation why Relæ topped the list:

Relæ’s simple unfussy aesthetic is matched by its low-impact approach to the environment: the chairs and tables are recycled, light fixtures LED, cooking is by induction methods, and local deliveries collected by bike. Furthermore, the restaurant partners with a local community centre and organic nursery, with all food waste used as compost. The team helps develop healthy recipes for local schools and offers four-year fully paid apprenticeships to culinary students.

This Danish dining beacon sits on a short stretch of small boutiques and coffee shops, just past the historic Assistens Cemetery (where Hans Christian Andersen, famous for his fairy-tales translated into more than 125 languages, and Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish existentialist philosopher and theologian, are buried). Praise for Relæ, operated by Christian Puglisi and Kim Rossen, alumni of one of the world’s legendary restaurants, Noma (which has produced many chefs now operating their own New Nordic restaurants) is well-deserved.

Perhaps unexpectedly (given Relæ’s lineage, reputation, and need for reservations in advance), diners are welcomed and hosted with a notable unpretentiousness. Its stated mission, simplicity with quality comes first, great details are just beneath, rings true. In place of showiness or pomposity is an enthusiastic and sincere commitment to local, seasonal, and sustainable sourcing; a depth of knowledge about the food prepared, plated and served; and an effort to use simple, 90-100% certified organic ingredients for its delicious food, with its clear flavors and textures.

Before the meal begins, a wait staff member brings over chilled, wet hand towels, infused with the refreshing scent of bergamot (the scent, like the menu, varies depending upon the chef’s choice). In a sliding drawer at your place setting, in a unique toolbox, are your utensils, a napkin, and a menu or, more accurately, an information/options card. At Relæ, diners are presented with two primary decisions: four courses or seven courses and omnivore or herbivore. The card notes that “our focus has always been on vegetables.” This statement and the execution of the menu ties in seamlessly with Michael Pollan’s famous advice in Food Rules to “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” Although provided with an information card, diners are not informed of what dishes await them until they are brought to the table.

Guests may also choose to add wine pairings, selected by the staff, for each course. The meal is pricey for diners on a budget, but certainly fair for such a credentialled restaurant, especially given the current favorable U.S. dollar to Danish Krone (dkk) exchange rate. In early summer, four courses (essentially three small plates and a dessert) are 450 dkk ($67 in USD at current exchange rates) while seven courses are 725 dkk ($107). The corresponding wine pairings are 395 dkk ($59) and 685 dkk ($102), respectively. As a matter of comparison, dining at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, the American restaurant included in the top five sustainable restaurants, is $218 per guest exclusive of beverage, tax and gratuity for the pleasure of “Grazing, Pecking, Rooting” at the Hudson Valley dining mecca.

Before our four courses appeared, we were served a snack. On our evening, the snack was a raw lettuce stack with overnight-fermented lettuce (fermentation started with some sugar) and goat cheese filled in between the fresh, crisp lettuce layers. This starter was well-constructed, somehow maintaining its stacked architecture over multiple bites, and provided a clean, sharp, flavorful introduction to the meal. We were also given two large slices of house-made sourdough, which had a nice moist crumb, charred crust, and light sourness with some olive oil on the side for dipping.

Since one of us ordered the omnivore and the other the herbivore menu, our first courses diverged. The herbivore received a dish simply described as “salted unripe strawberry” by the menu description we received after the meal (recall that dishes are kept secret until brought to the table). This dish was composed of green, this-season strawberries on top of green strawberries preserved last year, green onions, and salt topping the dish. It had a pleasing tanginess from the unripe strawberries and vinegar preservative with some sweet undertones. The omnivore received “venison tartar, new onions and pine,” which included a pile of ground raw venison topped with juniper needles on lightly braised scallions. The venison was tender and mild with the flavor primarily coming from the juniper and scallions.

The second course was identical for the herbivore and the omnivore: “potatoes, nettles and truffle.” Small, “new” potatoes cooked al dente were rolled in and topped with a bright green, creamy sauce made from the nettles (foraged, which is always fun to picture). The truffles were shaved on top, and a crispy nettle leaf was hidden between the potatoes. The dish was pleasantly salty with a rich texture and variety of complex flavors.

Before the third course, we were given a nice break, which was welcomed as the potatoes dish was intensely flavored. It also allowed a nice opportunity to strike up a conversation with the diners next to us (you’re seated close to others at Relæ). For the third course, the omnivore received “lamb from Havervadgård and fennel,” which was composed of two small slices of lamb sourced from the western coast of Denmark and roasted rare, over lamb fat and sliced fennel root, topped with a forest of fennel leaves. The flavors were uncomplicated — dominated by the sweetness of the lamb and the fennel leaves while the dish had a creamy base from the reserved lamb fat. The herbivore ate “spring cabbage, basil, and egg yolk,” perhaps the most beautiful and inventive dish of the evening. A large section of grilled cabbage was filled with sauteed basil leaves, and topped with a tangy and bright yellow benedict-like sauce and lemon parmesan shavings on top. It was a hearty, perfectly filling final savory course.

Dessert (“sage ice cream and rhubarb”) was the same for the omnivore and herbivore, featuring a dollop of softened ice cream flavored slightly but detectably with sage, topped with a rhubarb tuile “cooled at 60 degrees for 5 hours then frozen and cracked,” itself topped by a rhubarb compote. The dessert nicely summed up the characteristics of the whole meal, expressed explicitly in another mission statement on the restaurant materials: We love to cook tasty food in complicated ways from quality produce and serve it in all its beautiful simplicity.

Other notable features of the restaurant include the decorative ceramics, some of which come from the ceramic artist, Inge Vincents, known for her paper thin bowls, vases, cups and other containers. (Her wonderful keramiker inge vincents shop is just down the street from Relæ.) The interior design of the restaurant is unfussy; the open kitchen (seemingly required for a restaurant like Relæ) is right by the entry way and the kitchen staff greets you as you enter. A bar borders the kitchen while a long row of two-person tables and a parallel communal table run down the length of the space. Low lights hang above the individual tables and the brick walls are broken by light-filled (in July, at least, when the sun rises at 4:30 a.m. and sets at 10 p.m. in Copenhagen) windows with fresh flowers on the sills. Food is served on low-key handmade ceramic dishes. The restaurant appears to seat about 35 patrons, and reservations are necessary at least two months in advance, and possibly more now that it has been rated world-class. The toolbox containing the information card, silverware, and napkin is a fun and quirky touch, and builds excitement for the meal to come.

Perhaps the most unusual and innovative procedural element of the meal is that each course is served by the kitchen staff member principally responsible for assembling it. This touch eliminates one more middleman in the process of getting the food from the local providers to the diner and allows the food preparers and diners an opportunity to connect and share their mutual enthusiasm for the ingredients and dishes. In sum, Relæ provides a wonderful, innovative dining experience emblematic of the best New Nordic cooking and efforts to source local, sustainable ingredients and to eat a larger balance of plants than animals.

Taking advantage of Relæ’s location in the lively Norrebro neighborhood, we also enjoyed fresh caramels from Karamelleriet, just down the block from the restaurant as well as after-dinner drinks at Manfreds & Vin, a lower-key sister restaurant from the Relæ chefs, located on the opposite corner.

Relae, Jaegersborggade 41, 45.3696.6609, Dinner: Weds-Sat 5:30PM-9:30PM, Lunch: Sat 12:00PM-1:30PM, www.restaurant-relae.dk/en

(L. Bregman & D. Barrie 7/13/15)

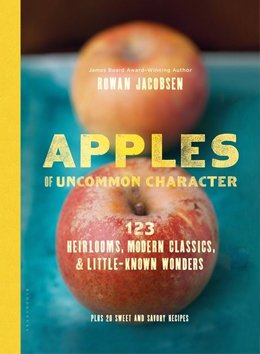

Apples Appreciated: Rowan Jacobsen’s Paean to Crisp, Sweet, Juicy & Complex

Thirty pages into Rowan Jacobsen’s Apples of Uncommon Character, 123 Heirlooms, Modern Classics, & Little-Known Wonders, Plus 20 Sweet and Savory Recipes (Bloomsbury USA, New York, New York, 2014) and I was considering how I had misspent my apple-eating life. I purchased whatever was inexpensive at the grocery store, without thinking about the whole apple universe that was out there. Picking those little labels off the skin without even thinking about what they meant, I never knew what stories lay behind those varieties.

Thirty pages into Rowan Jacobsen’s Apples of Uncommon Character, 123 Heirlooms, Modern Classics, & Little-Known Wonders, Plus 20 Sweet and Savory Recipes (Bloomsbury USA, New York, New York, 2014) and I was considering how I had misspent my apple-eating life. I purchased whatever was inexpensive at the grocery store, without thinking about the whole apple universe that was out there. Picking those little labels off the skin without even thinking about what they meant, I never knew what stories lay behind those varieties.

Jacobsen delivers those stories, and more. He inspires a wonder about the origin of apples you’ve had and those you’ve never been lucky enough to taste. His rich descriptions of more than 100 apple varieties, accompanied by Claire Barboza’s photography, will make you rethink this most commonly consumed fruit.

Jacobsen explains that apples were first domesticated in Europe, where carefully managed farms resulted in only a few varieties. It was when those seeds were brought to the United States, where trees had room to roam and grow in different climates, that they spread their wings. The story of the apple, in some ways, is the story of America.

The Newtown Pippin is one such American apple. The only variety to trace its origins to New York City (Queens), it was distributed in England by Benjamin Franklin on a visit. The English went nuts for the Pippins, but when they bought trees from the United States, they found the apples didn’t grow well in English soil, so they imported the fruit themselves. In fact, they imported so many Newtown Pippins that their domestic production was threatened and the government put a tariff on all imported apples.

People have been thinking about apples for a long time. Not just about how they taste or look, but when the trees produce fruit and how long the apples will last off the tree, all things I hadn’t considered before reading “Apples.”

Jacobsen breaks the book down into sections: Summer, Dessert, Bakers and Saucers, Keepers, Ciders\Fruit, and Oddballs. Each type has its own particular strength, much the way dogs were bred to specialize in a particular task.

Being an undisciplined reader, I skipped both the introduction and other apple sections and went directly to the “dessert” apples, which make up much of the book. Those are the ones meant to be eaten by hand without any processing, the ones tucked into your school lunch if you were lucky.

The standbys most of us know are covered: Fuji, Empire, Pink Lady, Braeburn, Golden Delicious and, of course, (my favorite) the Honeycrisp.

Each variety has a page explaining other names the apple is known by, its origin, region, season and taste. These descriptions alone make “Apples” valuable. Jacobsen won a James Beard Award because he can tell you how things taste. Oh, can he tell you how things taste.

“You can already smell the banana as you raise the uncut apple to your mouth. Once you break into the flesh, banana and pear esters surround you. The apple is mildly sweet, passingly tart, and tropical, like one of the modern fusion juices,” he says of the Ambrosia, an apple of Canadian origin. There is a lot of that wine-like description in “Apples.” Ozark Golds that have a “rich marzipan finish” and Mutsus “have some tartness and even a touch of astringency.” Admittedly, like wine talk, this can border on pretentious, but more importantly, it makes you think about how things taste.

It was when I moved past the familiar apples that I started to regret my misspent apple years. The Honeycrisp, beloved in my house, Jacobsen acknowledges, but there are other apples that sound (dare I say it?) far better than Honeycrisps. He describes one called the Blue Pearmain that he says was “among his most sublime apple experiences.” Another, the Esopus Spitzenberg (from Esopus in Ulster County, NY), is supposedly President Obama’s favorite apple. Obama isn’t the only president to like the Esopus Spitzenberg; upon tasting one, Thomas Jefferson decided he needed to fill his orchards at Monticello with them. Henry Ward Beecher said it was “the standard of excellence for apples of the Baldwin class…unexcelled in flavor and quality.”

I have never seen an Esopus Spitzenberg apple in my life, but that is going to change.

It was at this point in “Apples” that I made a life-changing decision: There are over 700 varieties of apples and I’m going to try as many as possible. I have lived too long to have tasted so few apples. I decided to create an apple “bucket list.”

Once you’re able to move beyond figuring out where you can buy an Orange Pippin or Esopus Spitzenberg and gawking at the photos, you’ll find an ingenious book that gives you the best apples to cook with and to use to make cider. It even includes a variety of apple recipes. Two pages at the end of the book entitled “Resources” note sources for (i) mail-order gift boxes of apples (including pre-Civil War apple varieties from Gray Wolf Plantation in New Oxford, Pennsyvania and the “fantastic” gift boxes of organic apples during the holiday season from Harmony Orchards in Tieton, Washington), (ii) mail order apple trees (including Trees of Antiquity of Paso Robles, California with its huge selection of organic apple trees and Vintage Virginia Apples of North Garden, Virginia with more than two hundred varieties of organic apples in the Charlottesville region), (iii) makers of artisinal apple ciders (including Steve Wood’s Farnum Hill Ciders of Lebanon, New Hampshire which according to Jacobsen “has the best cider orchards in America”), and (iv) apple festivals & events (including CiderDays held in early November in Franklin County, Massachusetts, the “highlight” of Jacobsen’s apple year and the “mecca for every serious cider enthusiast in America”).

The only drawback is that I wanted more. Every variety should get the kind of treatment Jacobsen gives the lucky 123 varieties he gives in “Apples.” Luckily, he gives credit to Spencer Ambrose Beach’s 1905 book, “Apples of New York,” which he says is the best book about apples around. Perhaps I’ll find what I’m looking for in there, or in visits to formerly unappreciated apple orchards and add another variety of the uncommon apple to my bucket list. Slow Food USA’s Ark of Taste (which lists the “varied and wonderful foods in the USA that have strong cultural and regional connections”) includes 14 varieties of apples with information and leads on places where they are currently grown (including the Newtown Pippin and Esopus Spitzenberg varieties noted above).

(Herb Terns, 7/1/15)

[Editor’s Note- Rowan Jacobsen’s erudite, yet humorous, American Terroir Savoring the Flavors of Our Woods, Waters, and Fields (Bloomsbury USA, New York, New York, 2010) which celebrates great American foods “that are what they are because of where they come from” was previously reviewed on this website. (FWB)]