Archive for June 2013

Untimely Death of Grenada Chocolate’s Founder In Accident

A few weeks ago, the brigantine, Tres Hombres, operated by a company called Fairtransport, set sail from the island of Grenada in the Caribbean to Holland with a load of Grenada Chocolate bars. Unloaded on to a large caravan of human-powered cycles pulling trailers, the approximately 18,000 chocolate bars were delivered throughout Holland to chocolate aficionados. The dream of Mott Green, the founder of the bean to chocolate bar maker, Grenada Chocolate, for the “carbon-neutral trans-Atlantic mass chocolate delivery” was a reality, captured in a video posted by Mr. Green just weeks before his accidental death on June 1. Sadly, the New York Times reported in Mott Green, A Free-Spirited Chocolatier, Dies at 47 by William Yardley that Mr. Green “was electrocuted while working on solar-powered machinery for cooling chocolate during overseas transport.”

A few weeks ago, the brigantine, Tres Hombres, operated by a company called Fairtransport, set sail from the island of Grenada in the Caribbean to Holland with a load of Grenada Chocolate bars. Unloaded on to a large caravan of human-powered cycles pulling trailers, the approximately 18,000 chocolate bars were delivered throughout Holland to chocolate aficionados. The dream of Mott Green, the founder of the bean to chocolate bar maker, Grenada Chocolate, for the “carbon-neutral trans-Atlantic mass chocolate delivery” was a reality, captured in a video posted by Mr. Green just weeks before his accidental death on June 1. Sadly, the New York Times reported in Mott Green, A Free-Spirited Chocolatier, Dies at 47 by William Yardley that Mr. Green “was electrocuted while working on solar-powered machinery for cooling chocolate during overseas transport.”

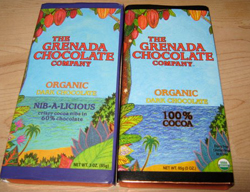

Grenada Chocolate’s bars were more than just praiseworthy “fair traded” chocolate. (Over a dozen chocolate makers are included in the chocolate directory on this website, including Grenada Chocolate, which nonetheless is in its own unique category.) In 1999, Mr. Green founded a chocolate company with a truly “transparent supply chain from farmer to consumer.” His idea was to create an organic cocoa farmers’ and chocolate makers’ cooperative. The cooperative farms 200 acres of organic cocoa and operates its own cocoa fermentary “one mile from our little factory” as noted on Grenada Chocolate’s website. Every activity involved in the production of its chocolate, from the planting and growing of the cocoa , to the fermenting of the fresh cocoa beans to the processing of the fine dark chocolate is done on the Caribbean island by the cooperative. Delivery of 18,000 Grenada Chocolate bars by a sailing vessel from Grenada to Holland perfected the extraordinary vision of Mott Green.

Because small batch chocolate-making is very rare in this era of commodity chocolate, Mott Green designed the cooperative’s own machines, based in design on those of the early 1900’s. He also refurbished antique equipment “to meet the requirements of our unique situation.” In making its small batch chocolate from organic Grenada cocoa, some ingredients, carefully chosen, from off-island were used by Grenada Chocolate: organic raw sugar, produced and milled by an organic growers’ cooperative in Brazil, and whole organic vanilla beans, grown biodynamically in Costa Rica.

Mr. Green’s memory will live on with the continuing operation of Grenada Chocolate. In 2012, Belmont Estate and Grenada Chocolate formed a close partnership with organic cocoa beans, purchased from local organically certified farmers, fermented and dried at Belmont for Grenada Chocolate’s small factory to produce its chocolate. (Grenada Chocolate and Belmont Estate are members of the Grenada Organic Cocoa Farmers Co-operative Society Ltd., that grow organic cocoa to make the product. The co-operative consists of about twelve farmers that have received organic certification through the German certifying company Ceres.) Shadele Nyack Compton of Belmont Estate has indicated that Grenada Chocolate’s unique operation will be continued.

In addition, Mott Green’s inspirational story lives on in the documentary Nothing Like Chocolate which conveys how Mr. Green found hope “in an an industry entrenched in enslaved child labor, irresponsible corporate greed, and tasteless, synthetic products.” The filmmaker, Kum-Kum Bhavnani, is a university professor by day and a filmmaker by night. Her first film was the feature documentary, The Shape of Water, narrated by Susan Sarandon (www.theshapeofwatermovie.com). Aware of the harsh conditions faced by the people, often children, who harvest cocoa in West Africa and elsewhere around the world, Bhavnani knew she “had to spread the word about how all of this might be done differently.” The three minute trailer for Nothing Like Chocolate whets the appetite to view the entire film.

Cocoa, the basic ingredient in the production of chocolate, has its historical origins according to archeologists in what is now Mexico. The ancient Olmecs “ate the sweet, pulpy fruit of the cocoa plant and likely cultivated it in 1000 BCE” [Edible, An Illustrated Guide to the World’s Food Plants, Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2008, www.nationalgeographic.com/books]. The entry on cocoa in this informative guide further notes that Cortes brought chocolate and the knowledge of how to prepare it back to Spain in 1527, but “it took a few more decades- and the addition of sugar and vanilla to the beverage- for chocolate to become appreciated in Europe. . . and in 1847, the first chocolate bar was created, and chocolate makers have never looked back. ” Mr. Green, who grew up in New York City’s Staten Island in a middle class family, found purpose in life as a chocolate maker on the island of Grenada. He enriched life on this “island of spice,” now known for its chocolate due to his energy and creativity. No doubt, Mott Green will be remembered as a chocolate maker par excellence.

[Frank W. Barrie]

Dublin’s Farm Restaurant in City Center South

Nestled at the southern end of central Dublin’s busy Dawson Street, just a stone’s throw from the verdant oasis of Trinity College, is Farm Restaurant. In Ireland up to about thirty years ago, locally produced food was something taken totally for granted. It was a country blessed with an abundance of native food. Ireland’s produce, although largely seasonally dependent, was not stressed by arduous journeys from far corners of the globe. Small farmers and local fishing fleets provided its meat and fish. Then affluence made its appearance and the Irish palate rebelled and yearned for more thrilling fare. Exotic dishes that called for long-haul ingredients such as avocados and mahi-mahi and passion fruit became all the rage.

More recently, however, in tune with local food movements elsewhere, a recalibration has occurred. There has been an emergence of informed appreciation of the value of native foods, fresh from local farms and waters or crafted by artisans. Significantly, the Slow Food Movement (founded in 1989 by Carlo Petrini as an outgrowth of his campaign against a McDonald’s opening near the Spanish Steps in Rome) has put down strong roots in Ireland, with Slow Food Ireland coordinating 14 convivias (chapters) throughout the country. It is here that Farm finds its niche. The restaurant was established some half dozen years ago with the stated mission to provide “affordable, homemade, locally sourced food, and as much organic and/or free range as [it] can.” It has prospered and now has a companion restaurant on Upper Leeson Street, a little over a mile away from its original location.

Farm announces itself on Dawson Street with a chalk-board on its outdoor patio, listing daily specials. Inside, the restaurant occupies a long, narrow room but due to its front wall of glass and interior of caramel-colored walls, pale wood floors, sleek tables and funky light fixtures, it has a streamlined, light and uncluttered feel.

On the spring day that I stopped in, the lunchtime menu included starters such as freshly made soup, homemade chick pea hummus and spicy organic chicken wings. Among main courses were Spanish omelette (organic eggs, mozzarella cheese, cherry tomatoes and baby potatoes), organic beef burgers topped with dry-cured local bacon and Gubeen cheese (farmstead cheese from the Ferguson family farm in coastal West Cork), and a wild mushroom and goat cheese risotto made with St. Tola goat cheese (from a herd of Saanen, Toggenberg and British Alpine goats reared on 65 acres of organic pasturelands in County Clare). Not to mention fish pie (salmon, cod and haddock in cream sauce, topped with apple and shallot mashed potato and a hint of cheese), a dish for which the restaurant is by now famous.

Main courses are accompanied by green salad or shoestring fries. Optional sides, such as champ potato (a traditional Irish dish made by combining mashed potatoes and chopped spring onions, butter and milk), sautéed onions and mushrooms and fresh vegetables of the day, are also available. The menu is clearly presented: in addition to a vegetarian section, each dish is accompanied by information about its properties, e.g., protein, gluten and vitamin content. Farm has an early bird menu (until 7 p.m.) and a childrens’ menu that successfully strikes the tricky balance between juvenile tastes and nutritious fare.

My attention had been caught by the day’s advertised lunch special, smoked salmon over pasta, baby spinach and tomato. This definitely had the potential to be interesting. Too much smoking and the intense flavor could dominate everything around it. On the other hand, in skillful hands it could prove to be a satisfying variation on an old Irish favorite. Feeling adventurous, I decided to go for it.

A neat feature of the restaurant is a little electric button on each table. I assume it’s a buzzer – although mercifully the patrons are spared the noise of any buzzing. When you are ready to order or when you require something, you simply hit the button and someone materializes to take care of your needs. In my case, it was Marina Sarosi, the friendly and informative manager.

I started with a selection from the varied wine and beer list, a Helvick Gold blonde ale, produced by Dungarvan Brewing Company, one of Ireland’s craft breweries. Launched in 2010, the brewery on its website notes its philosophy as one of purity: “We keep the beer in its purest form by bottle-conditioning it. It isn’t filtered, isn’t pasteurised and is naturally carbonated. We always start with the best quality ingredients: Maris Otter malt, full leaf hop cones and the limestone rich water of Waterford.” Served in a frozen glass, this outstanding blonde ale had a very refreshing, hoppy bite to it.

There need have been no worry about my choice of main course. It was excellent. The organic salmon was very lightly smoked (in house). Tossed with penne pasta in a light cream and mustard sauce and accompanied by baby spinach and sweet cherry tomatoes, it was simply delicious. The delicate flavors of the ingredients blended beautifully and not one overwhelmed another. The restaurant was lively with lunchtime activity. Diners at nearby tables seemed to be enjoying spicy beef noodles with vegetables and Farm’s famous fish pie.

Desserts such as organic ice cream or Bailey’s Cream bread and butter pudding were very tempting but it would have been overdoing things. I settled for a café americano.

For around €20, Farm’s central location, pleasant surroundings, quality food and very attentive service represented excellent value.

[Farm Restaurant (City Center South), 3 Dawson Street (Between Lord Mayor’s Mansion & Trinity College), 353.01.671.8654, Lunch & Dinner: Daily 11:00AM-11:00PM, www.thefarmrestaurant.ie]

[Eidin Beirne]

Tip Trips Up Phony Organic Sales at Farmers Market

Federal District Court Judge Gary L. Sharpe, based in Albany, New York, has sentenced Craig Acton, who operated Hoosic River Poultry, a small upstate New York farm in Buskirk (Rensselaer County) to serve two years on probation and complete 50 hours of community service for his “fraudulent use of a United States Department of Agriculture inspection legend on meat products” that he sold at New York City Greenmarkets. During a six month period in 2011, Acton purchased chicken from various conventional commercial sources and repackaged the chicken to sell it as organic at farmers markets in the Big Apple.

The Bennington Banner reported that Acton told investigators that a flood killed 1,000 chickens on his upstate New York farm putting him “in dire financial straits.” Acton marketed chicken he sold at the farmers markets in New York City as “farm-raised, free-range chickens with no medications or hormones added.” He purchased about $1,200 in chicken per week and sold it in the Big Apple for $5,000.

In the summer of 2011, the USDA received a tip from its hotline that Acton was repackaging conventional chicken and selling it as organic at farmers markets in New York City. According to a report in the Albany Times Union, “Investigators learned that Acton had been selling meat at greenmarkets for years with false inspection labels.” The Inspector General’s Office of the USDA was responsible for the investigation, which was the basis for the successful prosecution by Assistant U.S. Attorney Daniel Hanlon.

The USDA Office of Inspector General maintains a hotline for the reporting (anonymously or confidentially) violations of laws and regulations relating to USDA programs. This hotline at 1-800-424-9121 (or 202-690-1622) receives tips on criminal activities such as bribery, smuggling, theft, fraud, and endangermemt of public health or safety. The USDA’s Meat and Poultry Hotline receives more than 80,000 calls yearly at 1-888-674-6854. The majority of these calls comes from consumers regarding how “to properly handle their food, including food safety during power outages; food manufacturer recalls; food borne illnesses; and for inspection of meat, poultry and egg production.”

Maria Rodale in her powerful Organic Manifesto noted that “Chemical farms are in production on about 930 million acres in the United States and 3.8 billion acres globally.” In contrast, with 13,000 certified organic farmers in America, and a few thousand more who are organic but uncertified, organic farming practices are in use on only 4 million acres in the United States and 30.4 million acres globally. To ensure that food sold as organic is truly organic (deserving to be sold at higher prices) is of upmost importance, not only to protect consumers but also to motivate more growers to utilize organic farming methods.

Although Acton’s criminal conduct was reprehensible, in this age of globalization and industrial agriculture, news of rat meat sold as lamb in China provides a certain perspective on judging the ills of the world. As reported in the New York Times, “even for China’s scandal-numbed diners . . . . that the lamb simmering in the pot may actually be rat tested new depths of disgust.” Acton’s defense attorney, Assistant Federal Public Defender George E. Baird, Jr. noted that the chicken “that was repackaged was always done properly and under sanitary conditions, it was refrigerated during transport” and would not “cause anyone to become ill.” With the latest food scandal in China in mind, he also might have added, it was at least chicken. Closer to home, Frank Bruni in his must read column, Of Fraud and Filet, cited information from the conservation group Oceana that “of more than 1,200 samples of seafood from about 675 stores and restaurants in 20 states and the District of Columbia . . . one-third of these samples had been peddled as something other than what they were [emphais added].”

Given such food scams, it’s with some relief that the USDA has released a final rule on “country of origin labeling” (COOL) for meat products which took into consideration, in the words of Wenonah Hauter, the executive director of Food & Water Watch, the right of consumers “to know where the food they feed their families comes from.” USDA’s new COOL rules significantly improve the disclosure of information to consumers, and according to Ms. Hauter, “The final rule eliminates the vague and misleading ‘mixed origin’ country of origin label for meat and ensures that each cut of meat clearly displays each stage of production (where the animal was born, raised and slaughtered) on the label.” Hopefully, there are sufficient resources available to implement this rule successfully and ensure its integrity.

(Frank W. Barrie, 6/1/13)