How to Fight the Pesticide Giants Revealed In An Inspirational Story of Local Activism

Preaching precaution (caution employed beforehand or prudent foresight) isn’t the same as practicing it. And the ounce of prevention principle, seemingly instilled in us at birth, has long gone out the window where pesticide use is concerned. Touted as the farmer’s salvation before risks were revealed, pesticides spawned a massive and profitable industry that flourishes, like any drug dealer, by keeping its users hooked.

Preaching precaution (caution employed beforehand or prudent foresight) isn’t the same as practicing it. And the ounce of prevention principle, seemingly instilled in us at birth, has long gone out the window where pesticide use is concerned. Touted as the farmer’s salvation before risks were revealed, pesticides spawned a massive and profitable industry that flourishes, like any drug dealer, by keeping its users hooked.

As a political device, the Precautionary Principle – so named in the late 1980s – found a more secure footing in the European Union than it has in the United States or Canada:

In Europe the precautionary principle serves as a fundamental basis for generating sound public policy; public health and safety generally trumps potential threats to it. In the United States, however, dangers have to be established through what is generally termed risk analysis, meaning that ‘acceptable levels of risk’ are established. … Precaution tends to be more of an afterthought than a guiding principle in the United States, and more of a guiding light in Europe.

The quote comes from Philip Ackerman-Leist’s A Precautionary Tale, How One Small Town Banned Pesticides, Preserved Its Food Heritage and Inspired a Movement (Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, 2017) which tells the story of the small European village that took on and bested a corporate assault that would have spelled doom for family-scale subsistence farmers – which was pretty much everybody not growing pesticide-anointed apples.

Mals is a town of 5300 inhabitants in the South Tyrol, technically in Italy’s Trentino-Alto Adige region, but with a history that aligns it with the bordering countries of Austria and Switzerland. Owing to its ruggedly mountainous terrain, this Alpine region tends to pursue its own distinct identity, so when Big Apple began to move in and take over more and more of the area’s scant farmland, there was a sense of live and let live among most of the neighbors – but a few of them initially saw reason for concern.

Günther Wallnöfer, for example. He’s the first of several residents we meet during the course of this book, and he may have been the first to feel the ill effects of apple-spraying. Supporting a family on his 47-acre dairy farm would be easier if his operation were certified organic, he decided, what with the revenue increase such certification provides. He made the change in 2001; a decade later, his crop samples, which required annual testing to maintain his certification, sported pesticide residue.

Wallnöfer buttonholed Ulrich Veith, the young, newly elected mayor of Mals, to complain of the problem. Veith was the right person to consult, because they shared one thing in common: a deep passion for what they both dubbed a sustainable future for Mals.

This kicks off a saga that introduces the people who would launch the anti-pesticide movement, alongside historical portraits of the region. From medieval times through World War Two, it’s been an area prone to siege. Its mountains and valleys have offered natural defenses, while aiding its climate in a limited amount of specialized growing. But that climate is warming, allowing a longer growing season, bringing with it this brand-new siege.

Ackerman-Leist has his own connection with area, one that goes back to 1983, when he spent a semester abroad at the Brunnenburg Castle and Agricultural Museum. This was housed in a 13th-century structure in the South Tyrol, a few miles west of Mals. Ackerman-Leist returned to the castle a few years later to work at its orchards and vineyards. While he loved the agricultural diversification of the area, by 1994 he’d had enough of spraying pesticides on crops. Back in the U.S., he developed the sustainable agriculture curriculum at Vermont’s Green Mountain College, where he continues to farm and teach. He also takes his students to Brunnenburg to study its farming practices and museum. It was while preparing for such a tour in 2014 that he learned of the upcoming Mals referendum, and he was floored: It was the first time the citizens of any town in the world had ever voted on whether to eliminate the use of all pesticides in their community.

The history of apples in the valley is relatively recent; by 1945, the leaders of fruit cooperatives in the area formed its own organization to help the area growers produce their annual one million tons of apples, from a province about half the size of Connecticut with an average family orchard size of 6 to 7.5 acres. But they proved to be part of the problem. A well-established farming practice (in this case spraying pesticides to ensure a bumper crop of marketable apples) produces a strong sense of entrenchment.

The author’s journey to learn the history of this revolution included visits to Urban and Annemarie Gluderer, who switched from apple growing to an organic herb farm in the valley. They had to take action when the apple-growers on three sides of their property persisted in reckless spraying, and even after spending $200,000 for a fully-enclosed greenhouse setup to protect them from the drift, their harvests were showing contamination.

We also meet Edith and Robert Bernhard, who created a valuable seedbank and sought to protect that legacy; veterinarian Peter Gasser, a longtime member of a local environmental protection group who recognized the imminent pesticide peril; Franz and Pius Schuster, the fourth generation to operate the Bäkerei Schuster in the village of Laatsch, who felt the effects of climate change and pesticides on the local grain; and Johannes Unterpertinger, the pharmacist who became a spokesman for the effort, but whose outspoken manner brought personal threats and property vandalism.

Early in 2013, over 70 Mals residents formed the Advocacy Committee for a Pesticide-Free Mals, but the effort truly picked up steam when Martina Hellrigl and Beatrice Raas enlisted a group of area women to make their feelings known through a display that appeared overnight of banners hung throughout Mals. (If your German is good, you can read about their ongoing efforts at hollawint.com. Hollawint is an exclamation of warning in Tyrollean dialect.)

While the satisfying conclusion is (more or less) foregone, nonetheless efforts to fight the measure prohibiting pesticide usage continue. Most important, the trip we take through this book to get there is a fascinating study of how local activism, from people who never would have imagined themselves to be activists, can make a significant and life-bettering difference. And it finishes with advice on how to do just that in your own locality.

Plus, A Precautionary Tale is a discursive book, but in a good way, filled with engaging bits of history that help with understanding the subject region – however tangential those connections may be. Thus we get a chapter on Ötzi, the frozen, remarkably intact corpse discovered high in the Ötzal Alps, a corpse that had lain there for several thousand years. His digestive-tract contents provided an unprecedented look at the diet and travels of early man; the tools he carried offered new insight into the development of such. [Editor’s Note (FWB): Ötzi is credited with the first meal known to have been eaten by a human (a 5,000 year old meal) which was recreated and on display at the American Museum of Natural History’s exhibit, Our Global Kitchen, Food, Nature, Culture.]

Ackerman-Leist’s writing style has the casual, informative feel of good journalism, although his sometimes too-forced puns and wisecracks can prove distracting. But it’s more than a precautionary take: it’s an inspiring one. And it’s a story that’s not finished yet in Mals even as it begins to play out in other parts of the world. It should prove to be a valuable handbook as we all fight the necessary fight against the pesticide Goliaths.

(B.A. Nilsson, 12/3/18)

The Carrot Project Grows the Local Farm Economy

The Carrot Project assists small New England and Hudson Valley farms and local food businesses in becoming economically sustainable

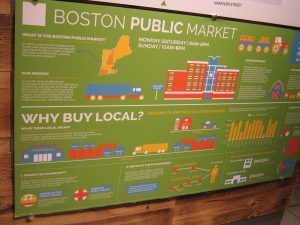

The Carrot Project’s fundraiser was held at The Kitchen of the Boston Public Market, an indoor, year-round market offering fresh, locally sourced food from nearly 40 New England farmers, fishers & food entrepreneurs

Siena Farms which supplies Sofra Bakery, recently reviewed here, coincidentally operates a farm stand at The Boston Public Market

The Carrot Project views as clients the farmers and businesses it works with directly. For over ten years, it has helped to build the financial management skills of its clients, and it takes pride in its 2017 Outcomes: 72 clients (whose service ended in the year) averaged an increase in net income of $28,500, 1767 farmland acres in production, and 47.5 jobs supported. And in 2017, it oversaw loans totaling $467,000 to current borrowers.

To meet its mission of increasing the number of profitable, viable farm and food businesses, The Carrot Project collaborates with various lending institutions. Earlier this month, its Ready to Grow fundraiser at the Boston Public Market was sponsored by Farm Credit East, SlowMoney Boston, Fresh Pond Capital, Eastern Bank, Honeybee Capital Foundation, and Trillium Asset Management.

The fundraiser, A Meet + Eat with Local Farmers, spotlighted two small farms, Three Maples Market Garden in West Stockbridge (Berkshire County, MA) and Ironwood Farm in Ghent (Columbia County, NY).

Three Maples Market Garden was started by Cian and Amanda Dalzell as a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm share, noting that they loved knowing the families who were eating our produce. They grow an impressive array of crops: squash, kale, carrots, cucumbers, peppers, eggplant, cabbage, tomatoes, turnip, rhubarb, zucchini, daikon, scallions, potatoes and radishes, as well as herbs, basil, sorrel, parsley, cilantro, dill, celery herb, tarragon, rosemary, and thyme. Cian Dalzell took a Making It Happen farm financial management course with The Carrot Project and has also trained to work as an instructor and business advisor to pay it forward.

Ironwood Farm is an impressive organic farm, certified organic by the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) of New York, on ten acres of leased land. The farm sells its produce at farmers markets, wholesale to restaurants, shops and resellers in New York’s Hudson Valley, and it also offers CSA farm shares. This certified organic farm is the collaboration of three women working together for seven years who hoped to achieve more together than apart and now make an income for each of their three households.

In addition, The Carrot Project at its recent fundraiser honored Scott Budde, who worked with the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MORGA) and Maine Farmland Trust to found the first credit union (Maine Harvest) focused on improving a local food system by lending to small farms and food producers, opening January 2019, with a capitalization of $2.4 million.

Investors and lenders helping to sustain the good food movement, rooted in small farms and local food producers, deserve gratitude for helping to counteract corporate gigantism, as evidenced by recent data released by the Open Markets Institute, showing increasing market share of the largest companies in many American industries, including the production of various agricultural products. For example, four giant enterprises, JBS SA, Tyson, Cargill and Smithfield have a market share of 53% (a 250% increase from their 21% market share back in 2002) of the Meat Processing Industry’s revenue (noted to be $123.2 billion in the data released by the Open Markets Institute).

Investors and lenders mindful of the ideals that monopolies undermine- like market competition, economic dynamic and individual freedom (in the words of David Leonhard in his op-ed, The Monopolization of America, NY Times, 11/26/18) deserve recognition.

Kudos for The Carrot Project in building the financial management skills of small farms and agricultural businesses and bringing together lenders and investors with well-managed small farms and local food businesses. The Project’s special recognition of two successful small farms and a caring investor/lender at its fundraiser earlier this month was a very special occasion worth celebrating.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/27/18)

Perfect Lunch in Late November: Root Veggies & Bean Soup Flavored With Middle Eastern Pizazz & A Local Farm Fresh Salad

Sofra Bakery & Café is a destination for neighborhood residents and visitors to the Boston metro area

In the heart of Cambridge (MA) near Central Square is chef Ana Sortun’s renown Oleana Restaurant serving farm to table Eastern Mediterranean (Turkey, Lebanon & Greece) food. No surprise to many that Boston Magazine included, what it called, “dazzling” Oleana in its updated list of the 50 Best Restaurants in Boston, noting that chef Sortun’s Cambridge paradise still excites with palate-enlivening fare.

Oleana garners special attention, not only for its menu with big flavor, but also for its locally sourced meats and fish, produce from its own 50-acre Siena Farm (25 miles west of Boston and run by Chef Sortun’s husband, Chris Kurth), artisanal wines and outstanding desserts by pastry chef Maura Kilpatrick.

Siena Farm grows over 100 varieties of vegetables free of chemical herbicides, pesticides, and synthetic fertilizers and also sustains a 500-member Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) community, included in our directory of CSA farms in Massachusetts. And in its 14th year of operation, Siena Farm also has two farm stores, in the Boston Public Market and Boston’s South End, as well as a stall at the Copley Square Farmers Market.

If dinner at the famed Cambridge restaurant is not doable, Oleana’s imprint also extends to a sister bakery & café, Sofra Bakery & Café, a little off the beaten path on the western edge of Cambridge, abutting Watertown, MA.

Sofra is a Turkish word with three related meanings depending on its usage: a picnic, a special table preparation of food, or a small square kilim rug for eating. Established 10 years ago, it has become a popular neighborhood destination, which also attracts visitors to the Boston area, to savor its café menu or its many take-away offerings, including prepared foods, house-made preserves, desserts, signature spice blends, etc.

On a recent visit to the Boston area, before a thee hour drive back home to Albany, NY, lunch at Sofra Bakery & Café was a special and energizing treat. Soup and salad was an easy choice when the special soup and salad of the day in late November sounded so appealing.

A large paper menu, hung high up over the pastry counter, listed the ingredients for the farm to table salad of the day in some detail: escarole, apple, fennel, feta, almonds, lemon vinaigrette. This was an appealing combination of ingredients that happily included watermelon radish, thinly sliced, on serving, that added an additional fall flavor to a perfect salad, expertly and lightly dressed. The dozen watermelon radishes included in my most recent CSA farm share from Roxbury Farm in Kinderhook (Columbia County, NY) took on new value seeing how they added flavor to a creative fresh salad.

The accompanying root veggies and bean soup, with just enough spicy heat, was served with crisp, flavorful crackers.

With the extraordinary desserts offered, not easy to decide on a pumpkin jam pastry. With a cup of Karma coffee (a small batch coffee roaster in nearby Sudbury, MA), the pastry was a perfect finish to lunch. The drive home on the Mass Pike was appropriately fueled for a local foods advocate. And return visits to Sofra Bakery & Café will be in store on future visits to the Boston area.

Sofra Bakery & Cafe, 1 Belmont Street (at Holworth Street, near Mt. Auburn Street), 617.661.3161, Sat, Sun & Mon 8:00AM-6:00PM, Tues-Fri 8:00AM-7:00PM

www.sofrabakery.com

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/19/18)

Large Study Of 70,000 Adults Suggests Organic Food Diet Reduces Risk of Lymphomas & Breast Cancer

Maria Rodale provides a convincing argument why we must remove chemicals from the process of growing, harvesting and preserving food in her must-read Organic Manifesto

A study recently published in JAMA (the peer-reviewed medical Journal of the American Medical Association), Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk (10/22/18), suggests that a higher frequency of organic food consumption was associated with a reduced risk of cancer. Although organic foods are less likely to contain pesticide residues than conventional foods, few studies have examined the association of organic food consumption with cancer risk.

Past epidemiological studies have found a higher incidence of some lymphomas among farmers and farm workers who are exposed to certain pesticides through their work. But sadly, once trusted epidemiology studies are scorned by the current E.P.A., now backed and influenced by agrochemical companies, as reported by Danny Hakim and Eric Lipton in Once-Trusted Studies Are Scorned by Trump’s E.P.A. (NY Times, 8/26/18).

Julia Baudry, a researcher with the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (at its Center of Research in Epidemiology and Statistics Sorbonne Paris Cité), the lead author of this large study of 70,000 adults, in a news article by Roni Caryn Rabin in the New York Times, Eyeing Organic Food as Cancer Foe (10/30/18), noted that We did expect to find a reduction, but the extent of the reduction is quite important. Researcher Baudry carefully added that although the study does not prove an organic diet causes a reduction in cancers, it strongly suggests that an organic-based diet could contribute to reducing cancer risk.

Nearly 70,000 participants in the study reported their consumption frequency of labeled organic foods ((i) never, (ii) occasionally, or (iii) most of the time). An organic food score was then computed (range, 0-32 points). Of the 68,946 participants, 78% were female and the mean age at the baseline was 44.2 years.

At two follow-up dates, May 10, 2009 and November 30, 2016, 1340 first incident cancer cases were identified: the most prevalent being 459 breast cancers, 180 prostate cancers, 135 skin cancers, 99 colorectal cancers, 47 non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 15 other lymphomas. The study found that high organic food scores were inversely associated with the overall risk of cancer.

We previously reported on a study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, an arm of the World Health Organization, that placed glyphosate (the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup) in the second highest category for cancer risk of probable carcinogen. Monsanto’s Roundup is the most widely used weed killer in America, with the vast majority of soybeans, corn, and cotton grown from Monsanto’s Roundup Ready GMO (genetically modified organism) seeds. Maria Rodale’s succinctly emphasizes in her must-read Organic Manifesto (Rodale, Inc. [distributed to the trade by Macmillan], New York, New York, 2010) that glyphosphate gets inside plants we eat and can’t wash off.

The Organic Consumers Association (OCA) recently noted that there are about 8,700 lawsuits pending against Monsanto, by people who allege that exposure to Roundup weedkiller is responsible for their cancer. And OCA emphasizes that most of the people behind these lawsuits have stories similar to the one told by Dewayne Johnson, during his landmark jury trial which resulted in a unanimous decision against Monsanto.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/10/18)

Scaling Up Means Closing Down Farmstead Creamery’s Pastoral Operation

No dairy sheep at pasture or in the barn in Old Chatham (Columbia County, NY) in Sept. 2017 after the relocation of Old Chatham Sheepherding Co.’s Friesian sheep to Locke (Cayuga County) in the Finger Lakes region of upstate NY

Sheep no longer grazing on grassy Old Chatham pasture land (but instead fed “locally sourced hay and grain”) with tubes of hay stored on nearby fields

The creamery in Old Chatham scheduled to close at the end of October 2018 but may keep operating until the end of the year.

Woodstock organic frozen vegetables are not grown in Woodstock (Sullivan County, NY) and sometimes are sourced from Chile and Mexico, so no surprise if Old Chatham Sheepherding Co. branding remains in use, but the marketing language on the Black Sheep Yogurt containers certainly should disappear in the new year!

Flocks of sheep at pasture in the idyllic landscape along Shaker Museum Road in Old Chatham, in the northern reaches of Columbia County in the Hudson Valley of upstate New York, have become a mere memory. In early September, 2017, this advocate for farmstead yogurt and cheese makers (who recommends scanning our yogurt and cheese directories for a local source of artisanal dairy products), had a big surprise on a visit to Old Chatham Sheepherding Company’s farm and creamery to stock up on its Black Sheep Yogurt from the refrigerator cases at its unstaffed, self-serve, honor store.

No sheep on the 600 acres of lush, grassy pasture land (except for a neighbor’s small herd raised for their fiber and meat), and no sheep in the barn: The initial flock of 150 dairy sheep at the start of the farmstead operation back in 1994 had grown to over 1,000 East Friesian crossbred sheep in later years but were no longer to be seen in pastoral Old Chatham in late summer 2017. A sad discovery, the Old Chatham Sheepherding Company’s dairy sheep had been relocated to the Finger Lakes region of New York, and were now part of a flock of 2,100, milked twice a day, and fed a combination of locally sourced hay and grains.

And with no sheep left in Old Chatham, this local food advocate was troubled by the marketing language spotlighted on the popular Old Chatham Sheepherding Co.’s Black Sheep Yogurt containers that We produce our great sheep’s milk yogurt with care on our farm in Old Chatham, New York. How so, if all the sheep were now 200 miles away in the Finger Lakes region of New York?

Only after puzzling over this marketing language for nearly a year, I confess that the light bulb went on only after a recent visit in late October, 2018 to the farm in Old Chatham. I noticed some workers in all-white uniforms, including a white cap, coming out of one of the farm buildings which proved to the creamery, still in operation. A lawyer-like analysis focused on the verb produce. arguably could justify the continued usage of the marketing language on the yogurt containers.

Although the sheep were no longer in Old Chatham, the creamery located at the farmstead in Columbia County was still in operation. Ergo, the yogurt and cheese was still being produced on the farm in Old Chatham. Sheep milk apparently was transported from the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York to the creamery in Old Chatham to be made into yogurt and cheese. But it certainly was not the same as the yogurt and cheese produced from sheep at pasture in the pastoral setting in Columbia County from prior years.

To produce sheep or cow milk without grain goes well beyond modern dairy farming practices, and for that matter, organic milk norms. Grazing dairies deserve special recognition and support from consumers and earn the premium pricing levels for their products by mindfully maintaining adequate pasture land for their ruminants a/k/a bovidae (cows are bovines; sheep, ovines; goats, caprices). We take some pride in offering directories of such yogurt and cheese dairies.

Last year, we reported on Consumer Reports’ recommendation for consumers to choose grass-fed meat and dairy products. This consumer is also impressed by farmstead dairies like Painted Goat in Garratsville (Otsego County, NY) and Black Pearl Creamery in Trumansburg (Tompkins County, NY) that give their goats and sheep, respectively, a rest from milking in winter months!

By the end of 2018, the creamery on the farm in Old Chatham will be out of operation. Presumably, beginning in 2019, the marketing language on the Black Sheep Yogurt containers, which troubled this local food advocate, will also be a memory. No doubt Old Chatham Sheepherding Co. has become a branding that is very valuable. It seems likely that it will retain some commercial life.

Woodstock organic frozen vegetables sold at my hometown Honest Weight Food Co-op also offered a surprise for this consumer on realizing that these frozen vegetables did not share any link to famous Woodstock, New York, other than a name. Mexico and Chile were often noted in smaller print on the packages as the source of the frozen vegetables for sale with that branding.

In short, consumers should be wary and read labels carefully. Branding can be deceptive. This consumer when shopping occasionally for organic frozen vegetables much prefers Stahlbush Island Farms’, also stocked by the Honest Weight Food Co-op. Check out its website and compare it to Woodstock’s, and you’ll see why. Stahlbush Island Farms cultivates 5,000 acres in Oregon’s Willamette Valley on its family farm, and it’s easy to pinpoint on a map where its frozen vegetables come from. Woodstock is an agribusiness with 250+ products in over ten categories and touts that more than 70% of its products are domestically sourced. Not so easy for the consumer to know exactly where those frozen vegetables come from.

(Frank W. Barrie, 11/2/18)